Nicole Rudick’s What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined: An (Auto)biography of Niki de Saint Phalle (Siglio Press) is a hybrid: both a biography and autobiography of the artist, told in images and words.

The Museum of Modern Art once described Saint Phalle’s output—which ranges from sculpture gardens to prints to theater sets to jewelry—as “overtly feminist, performative, collaborative, and monumental.” Rather than explain Saint Phalle, Rudick chose instead to work with a trove of rare and previously unpublished writing, letters, paintings, drawings, sketches, and other works on paper from the artist’s archive in Santee, California, and sequenced these materials without analysis or interpretations. The result is an intimate account of Saint Phalle’s life and creative concerns and an unconventional, utterly unique mode of life writing.

The Museum of Modern Art once described Saint Phalle’s output—which ranges from sculpture gardens to prints to theater sets to jewelry—as “overtly feminist, performative, collaborative, and monumental.” Rather than explain Saint Phalle, Rudick chose instead to work with a trove of rare and previously unpublished writing, letters, paintings, drawings, sketches, and other works on paper from the artist’s archive in Santee, California, and sequenced these materials without analysis or interpretations. The result is an intimate account of Saint Phalle’s life and creative concerns and an unconventional, utterly unique mode of life writing.

I first met Rudick in 2011 when she was managing editor of The Paris Review. We worked together on several dozen online pieces, including the Review’s first excursion into mixed media, a thirteen-part series called Big, Bent Ears. The collaboration influenced my book Gene Smith’s Sink, which is informed by our ongoing, open-ended conversations about the mysteries of life writing.

Rudick and I spoke via Zoom about her two decades of interest in Saint Phalle, why a traditional structure didn’t fit the subject, and the historical lack of women’s voices in the fields of biography and autobiography.

— Sam Stephenson

When did you first come across Niki de Saint Phalle’s work?

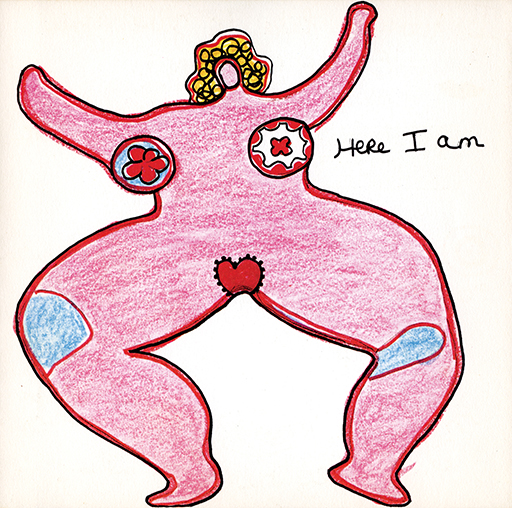

It must have been sometime when I was in high school or college. I was reading about somebody else when her name came up. She was French and I loved French things, and I must have seen a Nana, or something related to the Nanas, which are all about women and brightly colored—so she brought together all of the things I was interested in. Her work has been on my mind ever since then.

Did you know the whole time that one day you would write about her?

I didn’t know. It took me a long time to understand that I could think about art in this way. I grew up in Denton, Texas, and my mother worked in Fort Worth, near the Kimbell Art Museum, the Amon Carter, and the Science and History Museum. Whenever my sister and I would go to work with her, she’d take us across the street to the museums, especially the Kimbell, which is one of the best small art museums in the country. Louis Kahn designed the building. It’s a series of concrete barrel vaults with diffused natural light coming through skylights and huge concrete slab doors. Lots of travertine and white oak. It feels like a tomb—in the best way possible!

Seeing art there was most definitely formative. I remember seeing the Barnes collection, a show of Jain art, the Terracotta Army, work by Noguchi, Georges de la Tour, Old Masters. I was obsessed with Impressionism and post-Impressionism for a long time. But when I went to college, it never occurred to me that art was something I could study. I took my first art history class when I was a junior, and it was a revelation.

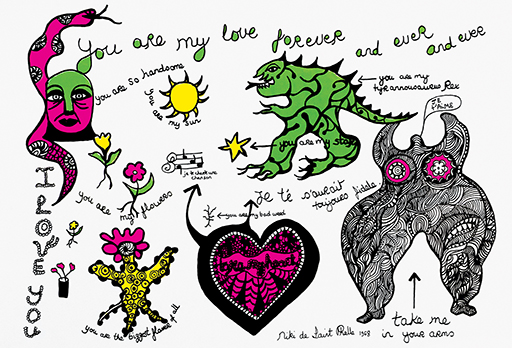

I moved to New York after college and got my master’s in art history at Columbia. I worked at Artforum and Bookforum for about eight years and never came across Saint Phalle’s work. It wasn’t until I was at The Paris Review that I saw her work in a back issue. In 1969, the Review published one of her “Dear Diana” drawings, thanks to their Paris editor at the time, Maxine Groffsky. It combines image and text, which is a form I’ve written a lot about, and being reminded that she worked in this way got me thinking about her art from a biographical point of view.

I’m interested in your focus on primary documents.

Archival materials, interviews, artist writings—that’s where I always start. That’s where I am most comfortable. In college—I went to Trinity University, in San Antonio—the emphasis in art history was on primary documents, not theory, and on analyzing the form of a work of art. Those approaches have really stuck with me. Columbia introduced me to theory, and I used those ideas for support, but theory is never primary for me.

When did the idea for this book arise?

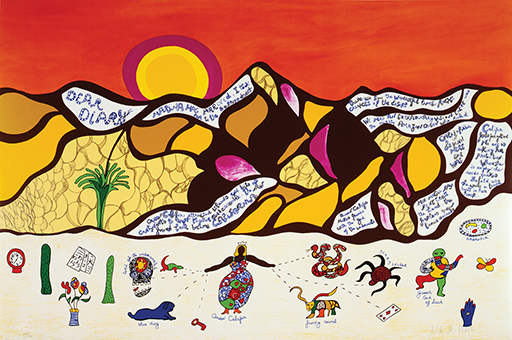

It began to take shape around 2015 or 2016. I had enough of a sense of her works on paper that I knew they were deeply and intimately autobiographical, and I thought there were enough of them to tell her story. When I went to Saint Phalle’s archive, outside San Diego, I found many other things—unpublished writing, serial drawings that addressed her inner life, rarely seen autobiographical works on paper. It was more than I’d hoped for. And that’s also when I realized I didn’t need or want to include anyone else’s commentary. Her voice in these works was so present, so strong.

How had you imagined including commentary?

I had thought that I would supplement her material by interviewing friends and family of hers, to fill in the gaps or offer insights. But in the archive, I read through a binder full of just these sorts of interviews that were done after Niki’s death and realized that, as would be true with anybody, if you ask someone about a person, and then ask someone else about the same person, you get two different stories, two different people. I mean, you know this from working on your biography of Gene Smith. Who knows the truth of a subject? Is there ever a truth of a person? I realized that each of these people who had been close to Niki saw something different in her. I didn’t want that in the book. Her voice was so strong in the artwork and writings she left behind and that was enough. I wanted to tell the story from her point of view.

The word you use in your introduction to describe interviews with people who knew Saint Phalle is “claim.” They were all making claims about her. They were claiming her, not letting her be.

They were claiming some sort of truth about her. My intent isn’t to denigrate or disparage those people or to imply anything malicious. It can’t be helped. We behave differently around different people, and that produces different versions of ourselves. It’s like “phone voice”—when you get on the phone, you talk differently from how you do off the phone, and it depends on who you are talking to as well. Two people may understand you in very different ways.

As we age, we change too. I’m not the same person I was twenty years ago. That person is still in me, but if you had interviewed me twenty years ago as opposed to interviewing me today, I would be quite different. That’s an idea worth pursuing, but it’s not exactly how I wanted to approach this book.

You let Saint Phalle’s words and drawings tell the story and it makes them explode off the page. As I read, I thought: In a normal book, the author would jump in at this point and connect some dots and add commentary, but if you had done that, it would have diluted the power of Saint Phalle’s art. It takes a gifted and brilliant person like Saint Phalle to leave behind documents with that kind of power, but then the decision to take yourself out of the presentation indicates such a lack of ego on your part. Did you and Lisa [Pearson, publisher of Siglio] discuss this approach from the outset?

I knew Lisa was the only editor who would let me do it this way. It’s characteristic of her entire endeavor. It’s hybrid, neither one thing or the other—that’s the realm where Siglio functions. She immediately grasped what I had in mind and wanted to publish it, without hesitation. She never doubted my approach. Her confidence helped keep me going because I have to admit there were times when I didn’t know if the book was going to hold together.

Ruth Scurr’s unusual biography of the seventeenth-century writer John Aubrey is the closest model, and I kept her book on my desk during the entire project. Whenever I had doubts, I would pick it up and read a few pages and feel I could keep going. It was a talisman for me. It was hard not to insert my opinions into the book, to analyze Niki’s work, because I do have opinions about it, but I knew this book wasn’t the place for those opinions.

The book opens with an insightful letter that Saint Phalle wrote to her mother. It’s stunning on one hand and electrifying on the other because, as a reader, you realize you are dealing with something unusual.

I believe that’s who she was. She wouldn’t have made the art she did if she weren’t someone who was capable of thinking intently about her own feelings. The monumental sculptures and sculpture parks took an incredible amount of will and desire to create, and yet throughout her career, she was invested in collaboration and inclusion. She was not egotistical but also did not negate herself. That’s a fascinating balance.

Her work really is her life. I can’t think of another artist where that is so clear and moving, and if you insert a critical or historical voice, it does something to reduce it.

I think it’s true. I think that’s one reason why I never quite heard her voice in any of the catalogs. Maybe it’s an unfair comparison. Exhibition catalogs involve criticism and analysis, and that type of work is important and necessary. As are more conventional biographies. I’m not saying my book is the way all biographies should be—the form should be dependent on the subject. I don’t know many artists whose work could support this kind of narrative. Saint Phalle is unique—she put so much of her life story in her work, which makes this possible. The books I laid out in my introduction, including yours, showed me that many forms are possible in biography and autobiography, and those forms do what the writer and the subject need them to do. You set out to write a traditional biography of Smith and then realized it didn’t seem quite accurate, no matter how many facts you compiled.

When I think of her many traumas, I wonder what anybody could add to her own account. Even comparatively minor moments, like when she’s a kid in a boat with her siblings and parents, and things get wild and it starts to feel like the boat might sink.

She wrote about that boat scare in her memoir that was published in 1999. Most of the text was written later in her life, retrospectively. We remember certain things, and not others, for a reason, and she thought the boat incident was important enough to include in her memoir. Maybe it didn’t quite happen in the way she remembers, but that doesn’t always matter. This is an idea I got from Nathalie Sarraute’s memoir Childhood. She wrote it in two different voices, but both are hers. One voice recalls scenes from her childhood, and the other voice occasionally calls the first one out. At one point, the first voice describes the memory of a picture from a children’s book, and the second voice says, “Wait a minute, are you sure you’re remembering that correctly? Shouldn’t you check?” And the first voice responds, “No, what’s the point? What is certain is that that picture is still associated with this book and that the feeling it gave me has remained intact.” The sensation that stuck with her, in other words, is what she had to draw on.

One example that comes to mind is when Saint Phalle writes about being expelled from Brearley. A standard biography would do a lot of work to figure out what actually happened. But you’ve already learned that she was reprimanded by a grade-school principal for writing pornographic stories, so you know that it’s probably something along those lines.

She painted all the fig leaves on the statues red, and that’s why she got kicked out. It’s a funny story, but it’s mentioned in conjunction with her so frequently that I didn’t think it needed to be in my book. I think it’s even in her Wikipedia entry.

In my biography of Smith, there’s very little about his Life magazine work and that’s what he’s most known for. Every time I started writing those sections, I’d feel waves of desultory feelings wash over me. I just didn’t think it was very interesting. The book probably would have sold better if I’d left them in.

It’s odd to think about the necessity of including things that lots of people already know. I suppose not everyone knows about the Brearley incident, but it felt enough like a rehash, and I wanted this story of her to surprise the reader, as much as possible.

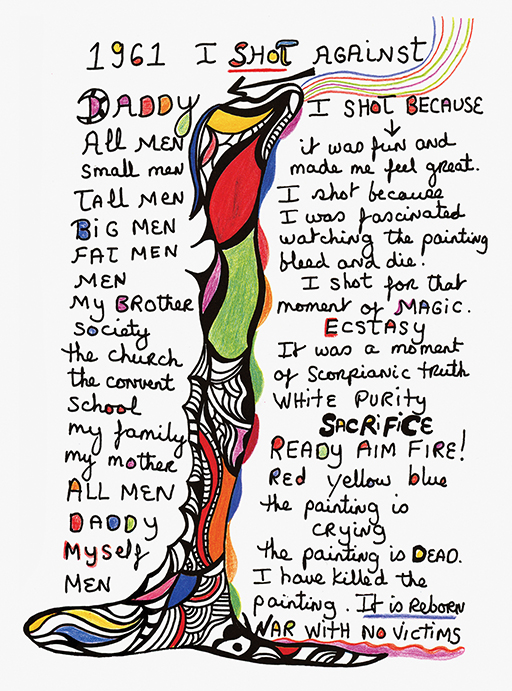

After her shooting paintings, she writes, “From provocation I moved into a more interior, feminine world.” Do you think she stayed in that world for the rest of her career?

That statement is a little misleading or simplistic. It’s certainly true that she moved into a more feminine world, but the works she made after the Tirs, or shooting paintings, and before the Nanas are quite complex and make an interesting transition between the violence of the Tirs and the buoyant Nanas. She made sculptures and sculptural reliefs of various women—witches, mothers, brides, whores, as she put it. The surfaces of the works are rough and embedded with toys and little objects. They’re kind of frightening. They remind me of the reliefs she was doing before the shooting paintings, where she embedded knives, axes, saws, and other sharp objects into the surface of the work. After the Tirs, there’s still a sense of violence, and also a kind of witchiness. I feel like calling them interior and feminine doesn’t fully get at what she was doing. She also didn’t start making Nanas and continue just with those for the rest of her life. She ranged around quite a bit, and, importantly, her interior perspective changed over time. If you read the book from beginning to end, she’s not in the same place later in the book that she was early on or in the middle.

The lack of explanation is so powerful. There are so many questions I have, like, did she keep in touch with her kids? But then I’m also left thinking, who cares? If I want to know if she kept in touch with her kids, I can go find out myself.

Those just weren’t questions I was focused on. The book captures her inner explorations and the spirit of her work. There are questions that readers will come away with. Is that a failing?

There are big, traditional biographies that I love, that are brilliant. But as I say in the foreword—and this comes from working with you for so long—how do you know where the boundaries of a life are? How do you know where to stop? Or when something doesn’t apply? You can cover so much and it’s never going to be complete. There may be information that comes along too late for inclusion. And there is also the fact that at some point you’re guessing what’s going on in a person’s mind. You’ll never really know.

I listened to a conversation between Imani Perry and Ruth Franklin while I was working on this book—they had both recently written biographies. One of them used the phrase “the tyranny of the archive.” You are beholden to what you find there and to what you don’t find there. You don’t know what you are going to find and you don’t know what you are looking for and you don’t know what isn’t there. When you attempt a biography, you live in fear of something being discovered later that you missed. Ruth Franklin learned during her writing of Shirley Jackson’s biography about a significant cache of letters that was found in somebody’s barn. She was able to use them for her book, but what if they hadn’t been found? What else is out there that the biographer doesn’t know about?

Even the biggest archive is just a fraction of what that person actually did in their lives, how they spent their waking hours. I’m interested in this idea that there’s more power in leaving things out. In music it’s often said that it’s not the notes you play, it’s the notes you don’t play. That line is attributed to Miles Davis or Thelonious Monk most of the time. There’s something relevant about that in what you’ve achieved in this book. The notes you play resound movingly because of what you’ve left out.

I think often about Albert Murray’s conception of the hero, and how it relates to jazz, and how in the breaks is where the hero can come in and be heroic, be creative. That’s their moment. Those gaps, or moments of disjuncture, are moments of opportunity for all kinds of things to happen. The things I left out, as you say, that wonderful analogy with jazz, gives the reader an opportunity to make linkages of their own. The Barthes quote I use in the book—a cooperative between the reader and the author and the subject—speaks to that. Every time I read the book, I notice something new, a different set of associations. Why would I want to try to explain that when I can instead let the reader make the discoveries and leave the book open to new thoughts and different connections? That’s the spirit in Niki’s work, too.

Here’s another passage from Saint Phalle: “Through painting I could explore the magical and the mystical, which kept the chaos from possessing me. Painting put my soul-stirring chaos at ease and provided an organic structure to my life, which I was ultimately in control of. It was a way of taming those dragons that have appeared throughout my life’s work, and it let me feel that I was in charge of my life’s destiny. Without it I’d rather not think about what might have happened to me.” I think a lot of artists become artists for that reason—a way of taming the dragons, processing those feelings and creating something they are in control of.

The reader can see Niki learning from herself, in a sense, and coming to terms with difficult matters and figuring out how to deal with them. The motif of the dragon is important. It’s menacing in much of her work, but in her book on AIDS, she made a drawing of a dragon with a chain around its neck, like a leash. She uses a very similar drawing in her tarot book, to represent the Strength card, and it says, “Only love conquers all.” In the AIDS book, which is a deeply empathetic work, she writes of the disease, “We have to learn to live with it.” There are many things we can’t dispel in our lives, and we must learn to live with them. It feels very intuitive to me, very right, very true. Her art is enthusiastic, but never wildly optimistic or Pollyannaish. A strong thread throughout the book is the connection between sorrow and joy. They travel together and are linked always. We carry them both in our lives, all the time. That seemed to be a significant realization for her.

Did you ever have any thoughts about whether she would like or dislike certain choices you made?

No. I mean, you can only ever really guess at that sort of thing, right? I suppose I didn’t start down that path because then I might second-guess all kinds of decisions. There’s no evidence that she planned to make a book like this. At the same time, she did leave what I chose to take as stepping stones. Because her work is so autobiographical, I never felt that I was reading too much into it, that I was putting more meaning into it than she intended. That’s why I keep pointing out the fact that you can’t do this kind of book with every artist. It’s dangerous to assume that art is automatically autobiographical. Fiction writers complain about this regularly—the assumption by readers or critics that the characters are modeled on the writer herself. It must be chafing to create a piece of art and then have people read your life into it. But Niki’s work was explicitly autobiographical, so it felt both safe and right for me to treat it this way.

When I was working on Gene Smith’s Sink, I asked my research assistant to go through ten years of the New York Review of Books, The New York Times Book Review, and the London Review of Books, and chart the coverage of biographies. Who were the subjects, who were the authors, and who were the reviewers? The results skewed heavily male in all three categories, around 80-85%. There are many reasons for that. One is that women’s lives weren’t and aren’t documented as often as men’s.

There’s a great book by Nell Dunn called Talking to Women that was originally published in 1965 and was reissued a few years ago by Silver Press in the U.K. Dunn published conversations she had with women friends of different backgrounds. Ali Smith wrote a great introduction to the reissue in which she discusses “the radical necessity of giving and having voice.” That line stuck with me while I was putting my book together, and I thought about the fact that it’s a relatively new idea as it relates to women and historically marginalized groups—both the “having voice” and the “giving” part, amplifying that voice, giving that voice space and time to be heard. Those two elements—the having and giving voice—animate my book.

For all the work Niki made about women and women’s experiences, I don’t think she necessarily sought to gender her art. Certainly, recognition that her father was able to leave home and have what appeared to be a second life outside of the home, that men had this power and she wanted it—she didn’t want to become a man. She wanted to be a woman with this power. She wanted to be a woman with that kind of freedom and freedom of experience. Working publicly, and being in some sense a public figure, allowed her to lay claim to her own story. The life was hers and it couldn’t be denied her.

I see that in the history of autobiography, where recording the story of your life and writing it down is certainly a way to lay claim to it, in addition to women writing themselves into history and insisting that their parts matter. Within the circumscribed realm to which women were restricted for so long, they were doing things and thinking things and imagining things and pushing out against those boundaries. But even today you can go to Target and see the kinds of clothes they sell for young boys and girls and it’s totally gendered. The boys’ shirts are all about adventure and being wild, and girls’ are about being kind and really about self-effacement. Kindness is not overrated, but the way we expect girls to be versus boys isn’t much different from a hundred years ago, only now it’s a capitalist mandate. Niki refused to deny herself and refused to deny a desire for a life outside the home.