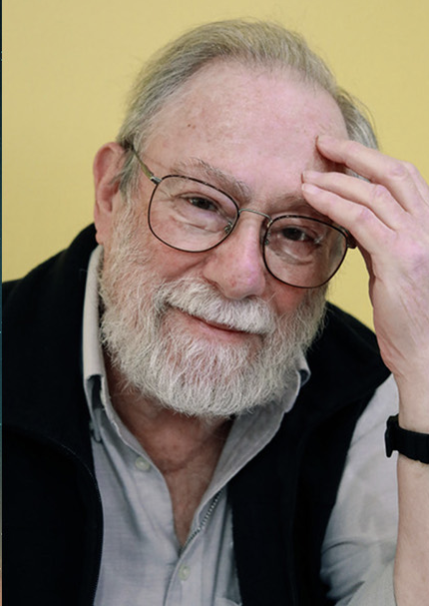

Marvin Bell: A Remembrance

Marvin Bell, who died in December 2020 at the age of 83, was a poet of relationships. Not expressly autobiographical, his work nevertheless did not shy away from the intimate and the personal. And yet, it also managed to be global, political, mythic, an exploration of both the human and the natural world.

“There is a kind of physical reality,” he once told the Ohio Review, “that we all share a sense of. I mean, we might argue about what reality is, but we all know how to walk across a bridge—instead of walking across the water, for instance. And it seems to me that one definition of modesty in poetry would be a refusal to compromise the physical facts of what it is that is showing up in one’s poems.”

It seems strange to describe such a capacious talent as modest, and yet in the most essential sense, that’s precisely what Bell’s work is. Not in terms of its ambition, or the clarity of its language and conception, but in the light touch of the poet in the world. Bell, in other words, is always gazing outward, even when he is writing about himself. He is interested in our relations with one another, with space and landscape, and with the unavoidable realities of mortality and death.

In his “Dead Man” poems, for instance, he takes as a recurring epigraph the Zen admonition, “Live as if you were already dead.” It’s a dichotomy, such a statement, a contradiction—and yet, at the same time, a kind of code. The idea is to aspire to a condition that one cannot reach, which only raises the stakes of the poems. In “About the Dead Man’s Recent Dreams,” Bell makes such a paradox explicit from the opening lines:

Call them ravaged castles in the air.

Think them fancy, fantasy, reverie or romance.

Dismiss them as head trips and chimeras.

He sees them day and night, call him a woolgatherer or stargazer.

He cannot stop his seeing what is not there.

Bell was a worker; he was writing and teaching until his final days. We are honored to present some of these last works in this issue of Air/Light. What you’ll find is a wide range of material: Bell’s final lecture, “Bloody Brainwork,” which is a vivid evocation of process; an audio conversation about Bell between the poets David St. John and Christopher Merrill; and a selection of previously unpublished prose poems Bell and Merrill wrote in collaboration with one another—single paragraph dispatches (“paras,” the authors called them) that reflect, through the back and forth between two long-time friends and colleagues, the uncertainty and constancy of a changing world.

“Poetry,” Bell once observed, “gave me a way to express everything at once. That is, it gave me a method by which to say more than words can say.” If this seems another conundrum, that’s the point precisely, to turn language into feeling, to express our tenuous and tenacious engagement with the world.

Marvin Bell: A Remembrance

- “After the Fact” by Marvin Bell and Christopher Merrill

- “Emeritus Talk: Bloody Brainwork” by Marvin Bell, both recording and text

- Marvin Bell: A Discussion of his Career with Christopher Merrill and David St. John