1

By the time the stay-at-home orders came down, I had already begun distancing myself. My household became a permanent workspace: office rotations with my partner and a room where my kid could complete fourth grade online. Those first weeks, as people started to arrange themselves as either the Ones with Free Time or the Ones Overworked (Home Edition or the riskier Out in the World Essential Workers Edition), I felt my energy dry up from working on video and having my family around without a break. There were those who made sourdough and those who dove back into their creative projects and posted about it, constantly, online. Meanwhile, people were falling ill. People were dying. I fell into COVID confusion, unable to reconcile the part of me that loved knowing I must stay at home with the part that had to stay awake, concerned about the crisis and its effects on my community. I typically write daily, two pages in the morning, and that didn’t end with the pandemic—but otherwise, I felt estranged from any desire to write. Instead I got interested in other people’s projects. If I couldn’t write, I could be an audience.

This led me to television. First, two reality shows focused on fashion: Making the Cut (reuniting Heidi Klum and Tim Gunn, post-Project Runway) and Next in Fashion (Tan France offering an amiable connection for fans of Queer Eye for the Straight Guy). These shows got me interested in a free online course called “Fashion as Design,” offered by the Museum of Modern Art. All of a sudden, I was reading PDFs and watching short videos about the emergence of the stiletto heel or the jumpsuit. Why do we wear what we wear? asked the PDF. This question both gained and lost importance as I tried to figure out what to wear each day. I thought of all the fantasies, decades’ worth, of making my own clothes. Instead of banana bread, maybe I would locate a sewing machine and online classes, and emerge from the pandemic with a closet of new clothes?

In fact, I did not even finish the online class. Why do I wear what I wear? I thought as I dressed my top half to meet clients for Facetime sessions. It took two months to figure out that I could wear the same outfit all week, throwing it into the dryer, if necessary, to refresh. That and some lipstick, which made me wonder if lipstick might brighten my groundhog days in front of the computer, where I couldn’t avoid my own image looking back from the flatness of the screen.

When my kid attended Zoom school and my partner took the office, I made myself comfortable in the TV room. I watched part of a film about the making of a Steely Dan album on a channel that airs only music documentaries; then I switched to Beat Bobby Flay. Bobby is a chef with a number of books and TV shows and restaurants, and every episode culminates with him competing against a guest chef to make the guest’s signature dish. Three judges do a blind taste test, and we see if the guest can “beat Bobby Flay.” Bobby meets every chef with respect, sometimes admiration, and when he loses, as he sometimes does, he warmly congratulates his competitor. The neutral face he wears and his posture, which seems natural, comfortable, and authentic, is appealing. Such a persona, even if a façade, represents one of the few kinds of male energy I want to deal with, ever.

Can it be an artist’s process when someone scales a 3,200-foot rock wall without a rope? If that someone is Alex Honnold free climbing El Capitan in Free Solo, I think it might. Watching, I took photos of the screen. In a few of them, Hannold appears to be wedged inside a long fissure. The closed captioning reads (heavy breathing). Indeed. I leaned into Free Solo at a point when I was analyzing my breathing, noticing any slight twinge in my chest, not long after a night when I was convinced my body was weathering the dreaded cytokine storm (heavy breathing). Maybe one of the most difficult and singular annoyances of the pandemic is the time spent considering any change in metabolism, any slight heat rippling over the skin, any change from the everyday aches and pains of being an older human. Which is maybe why I have lost hours and hours to television.

2

Not long before the pandemic, I watched Midsommar. Back then, I spent most days at home alone. My family was at work and school, and I knew they wouldn’t have any interest. (One of them is nine years old and recently flipped out when I tried to screen Jaws. It’s a classic film, and you loved Close Encounters of the Third Kind, I said. That same guy is in it. Richard Dreyfuss. And there are funny parts. And the shark does not look real. But she began screaming, hot tears flowing, during the first few minutes as the shark violently attacked the swimming woman. We did not finish Jaws. Instead, she was lulled by YouTube and its tween influencers, the queer bizarre of Steven Universe, replaying scenes in Gumball over and over again until they loop like earworms in my head.)

As I watched Midsommar, I thought about the Twitter commentary when it came out. I knew that now, no one would want to talk about it, although my partner did listen to me describe the plot. Then she agreed to watch Hereditary with me. The prevailing feeling I had after both movies was disappointment. Last year, when I watched The Haunting of Hill House alone on spring afternoons, curtains drawn, staring down my 46th birthday, I was similarly let down. Such interesting premises, and yet so much left to be desired. I wanted to rewrite the series. I continue to search for horror films that will do what Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, and Poltergeist did to me as a child seeing them for the first time.

In the early evenings, when my family would come together from our separate spaces, establishing home as Home again, I counterbalanced some of the horror/pandemic drama by looking for TV we could watch comfortably with our nine-year-old. (This was before we understood that we would be in quarantine until May. And then June. And then July. And then, and then, and then…) My kid happened on a show called Zoey’s Incredible Playlist. I half-watched until a song made me zero in, and I realized that one of the main characters was Black, queer, and trans. Zoey became a bittersweet kind of comfort cupcake in the evenings, and when we had no episodes, we would turn to Absurd! Planet (I always appreciate the exclamation point), with Afi Ekulona voicing Mother Nature, who in this incarnation is a proud, hilarious, loving mother who wants to showcase the planet’s strangest animals.

When I was not watching TV, I was working. When I was not working or watching TV, I was cooking. When I was not doing any of those things, I was reading or sitting in the backyard, on the one lounge chair we had managed to procure at the beginning of the pandemic before backyard equipment became scarce. Here was another kind of viewing. From my blue chair, I could see an orange tree filled with fruit, some as small and green as tight little limes; a flowering bush, home to many finches; the plumeria that drops white petals that look like mushrooms all over the grass. The mourning doves make their calls, a sound I associate with the bottlebrush and eucalyptus trees from childhood. An overripe orange drops from the tree and every time I am surprised by the thud, how it sounds like a small body hitting the ground. The end. But it is not the end at all. It’s the beginning of another story, in which the orange becomes food for ants, beetles, flies, and decomposes into the rich dark shadowed dirt beneath the tree.

An exercise I make myself do is to focus only on what is in my visual frame. This helps when I’m overwhelmed by the news, or when I try to imagine the future. When I am reclining in the turquoise blue lounge chair, I pay attention to the lilies of the Nile, the birds and their stop-motion gestures, their micro-movements and flight patterns I start to catalog. Tomato plants burst out of the garden bed, lolling heavily until they are bound to a wooden trellis that allows them to climb. Silhouettes drift across the grass, reminding me of a scene from a recent dream, seeing shadows fly backward as in a cartoon. The glisten/vanish/glisten/vanish of a spider web that connects the sun umbrella to the birdfeeder, one long, semi-secret tightrope. The sun belts heat. My backyard is a place of prayer, of grief, a place I’ve pissed, a place where I’ve gathered friends and sat at tables and looked at the night sky together. This backyard is a container of hours, like the TV room is a container of hours.

3

I can’t call what we were doing with our kid from March until June “homeschooling” when I know actual homeschoolers. Rather, we were tech support and occasional math explainers or consultants lite. To date, she’s had more Zoom meetings than I have. Meanwhile, I was deep into Gentefied, and my nine-year-old could grasp the content for the most part. We’ve talked about gentrification—using our neighborhood of West Adams as an example—but this is a smart comedy about Boyle Heights, where my mother was raised and my grandmother lived for my entire childhood.

On Easter, a holiday we observe only to hide chocolates in plastic eggs around the house, we screened Fried Green Tomatoes. I texted Myriam Gurba, since many a queer of a certain age recalls this movie fondly.

“An Easter classic!” she replied. Lol. And with that, my household decided that this might be our annual Easter screening, a new tradition.

We also made plans to start screening other movies that we deemed “important” for the child. When I came across Mrs. America, I thought it might be educational, even if we had to sort the historical elements from the fictional. My kid was immediately taken with the opening credits, a colorful animated sequence, 1970s-style, “A Fifth of Beethoven” providing sound theatrics. Explaining the Equal Rights Amendment, Phyllis Schlafly, and Gloria Steinem seemed a good enough extra credit assignment. I may have received some extra credit myself when I showed my kid a photo taken of me with four other women, including Steinem, during my first writing residency at Hedgebrook in 2007.

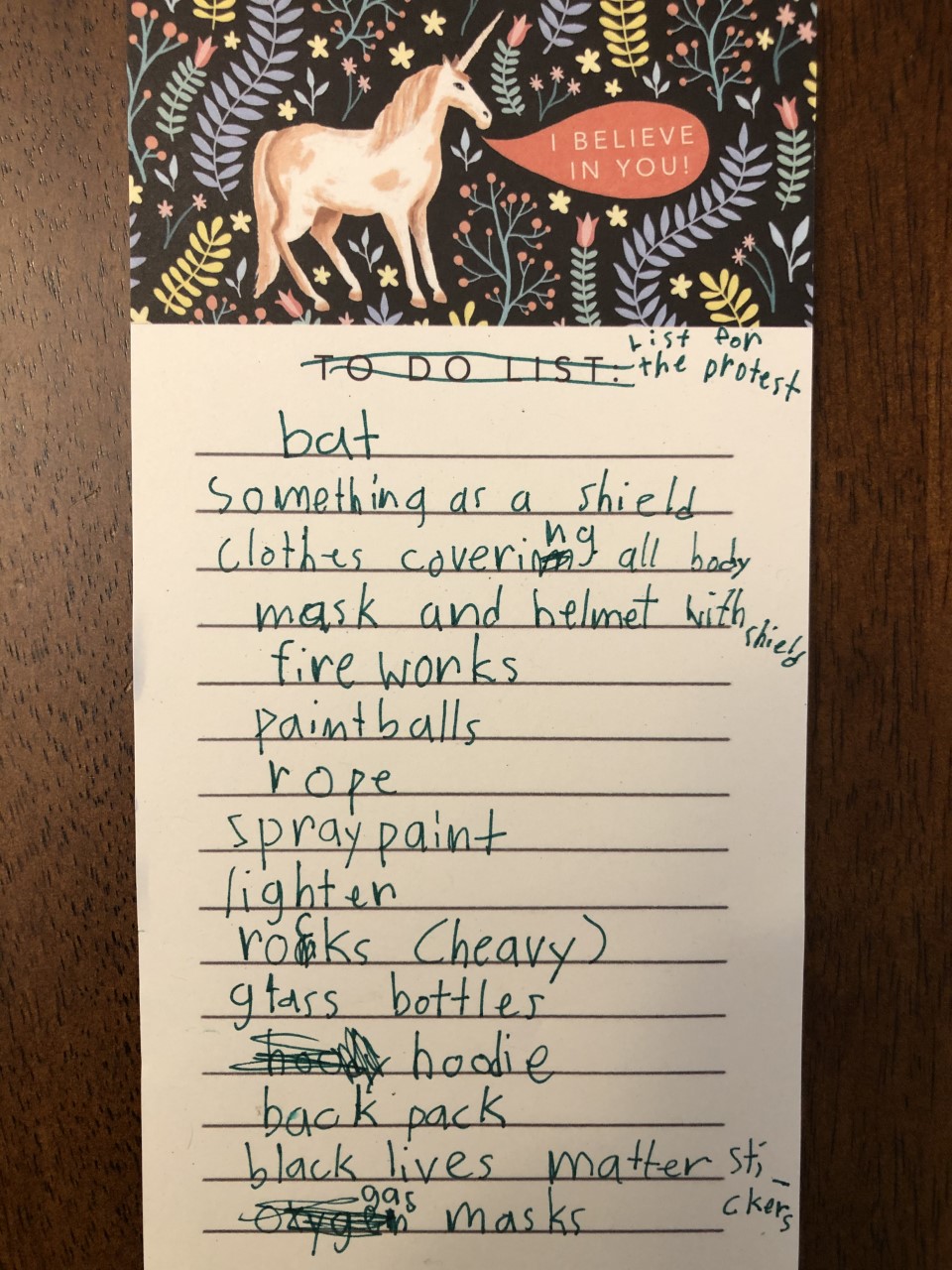

Around this time, our TV screen began to fill with images of people marching, people gathering, people protesting all over the country. If, like me, you were around for the 1992 Los Angeles uprising, to see Fairfax and Montana Avenues and Pan Pacific Park become sites of protest felt like reconnection of a sort. My kid asked about protests and our experiences. She was hungry for details. She made a list of what she would take to the protests if she could go.

“Something as a shield,” she wrote, “rope, lighter, backpack, gas masks.” I found some videos on YouTube about the 1999 WTO protests in Seattle, realizing that so much of my protest experience had been pre-cell phone, which means no footage unless we shot it ourselves. I rewatched If A Tree Falls: A Story of the Earth Liberation Front, while my kid asked why people were setting up platforms in a forest or plotting arson on empty buildings. The beginnings of many essays formed in my head. Depending on the source, my kid is either at the tail end of Generation Z or she is Generation Alpha. In any case, this kid and all the others are enduring a specific experience here in the pandemic that we, their parents and their caregivers, can’t begin to comprehend. What my kid knows is this:

Police are not our friends.

The president is not our friend.

Black Lives Matter.

And it’s good to make a list and be prepared for when we can safely protest.

4

The first TV show I ever binged was Six Feet Under. This was around 2006 or 2007. I would stand over my kitchen sink in Koreatown, staring at the EQUITABLE building framed perfectly in the window, thinking about the character Brenda. The amount of time I spent considering the characters, what they might do, what they had done … it felt as if I thought about them more than about the actual people in my life. Six Feet Under became my favorite show. I hadn’t yet had anyone close to me die. I was not yet a therapist.

Another favorite show is The Sopranos, which is what I’m binging now. There’s something retrograde about this, but it’s also weirdly comforting. I know the story arcs, after all; I know who dies, even if I don’t remember all the details. I know which episodes will make me feel physically ill. But I’m different than when I watched it for the first time. Much older, for one thing, but also a parent and a therapist. I’ve seen people I love die. So in this rewatching, I spend more time looking at the relationship between Tony and his psychiatrist, Dr. Jennifer Melfi, with the benefit of being able to pause, rewind. Scene after scene of male-heavy interactions fill my screen.

I think back to the last time I was in such a territory. It was my second or third time teaching at an arts center in New England, and as was customary, I was invited to a dinner. When I arrived at the restaurant, I realized that I was the last guest. The table was full of men, six of them, all of whom I had just met. I extroverted as gamely as I could as we ordered drinks, oysters, entrees. My history involves a few long-term, male-heavy experiences, even though for the last ten years, I cannot dredge up any memory of inhabiting such a space.

I trace my familiarity with men, or boys, to childhood, riding my bike with Chris, Brian, and Danny, playing Star Wars with Kevin, Matchbox cars with Scott, earnestly discussing UFOs with Pablo. I was the only girl in my neighborhood but I didn’t think about it much. Later, when every single boy left the neighborhood with their families—white flight from the east San Fernando Valley—I fit myself into another group of boys, some burgeoning men. Across the Valley I flew, most days of my adolescence, toward the garage of boy/men who drunkenly took bong hits between songs they strummed, beat drums to, shouted out. I was the hauler of these boy/men in my VW van, often the only one with a license that wasn’t suspended. My main activities were drinking, smoking weed, listening, observing, until I had rounded the corner to a place where I felt comfortable behaving as they did—spitting beer at someone for a stupid remark, starting a loud intoxicated argument, smoking cigarettes, loitering outside the liquor store. Afterward, I would fly back across the Valley, stopping midway at another house, a rental full of men in their late twenties and early thirties who either had sex with me or barely acknowledged that I was there.

When I think of these scenes now, I see how attractive they were—these men with the ability to live outside the bounds. I went to school, got good grades, had a job through twelfth grade. The boys across the Valley were occupational school dropouts, mostly without jobs, while the men in the middle Valley lived the lives of young dumb bachelors in the 1980s. The Land of Men, I call these spaces in my memory. I lived for a long time in The Land of Men. In the pandemic, however, I have even fewer interactions with men than I did before.

Meanwhile, Tony Soprano and his men parade across my screen. I wonder, as I usually do when confronted with this character, why I find him sexy, a feeling I want to strip out of myself like something I could kill. A virus. There are numerous references throughout the series to the “alpha male” and how Tony fits this archetype. I’ve had hardly any direct experiences with “alpha males,” because I have avoided them. My first were with my father and my half-brother, the latter of whom very much fit the stereotype, especially in his youth. I remember him taking my father to a Rams game when I was a child, and something happened—my brother drunk and in a fight? This was not uncommon when he went places. I wouldn’t come across my next alpha until adolescence: a peripheral figure in the dark garage in Reseda who seemed unlike the boy/men in my crew. This man worked in the porn industry. He was louder, more shrewd, and uninterested in the bullshit the boy/men found compelling. I harbored a private crush on him until I moved to Olympia.

Several years passed until the next alpha presented himself to me on a date; we went to a Thai restaurant and he ordered for both of us. What the fuck? I thought, and let him. Later that night, at the White Horse, he strongly suggested that we drive to Vegas. We were on date number two. Every gesture and move felt calibrated to make me say yes to a road trip at one a.m. When I say “strongly suggested,” many women will already understand that he would not leave it alone. He knew I was seeing another man and called him, with sneering vigor, “a wheatgrass-drinking pussy.” I laughed loudly, maybe inwardly agreeing. We never went to Vegas, but I thought about him a lot. I think of him now when I see the men on the screen, bulls in a china shop, blockheads with guns and old untreated traumas. So why in the hell would I find Tony Soprano sexy? I asked my partner, who identifies as gay, lesbian, queer: Do you find Tony Soprano sexy? Not James Gandolfini, but Tony Soprano. She didn’t hesitate; she said, yes, she found him sexy and that James Gandolfini was also sexy. Hmmm, I said, and thought about Tony’s grin.

In 2018, Robin Green, the only woman to write for The Sopranos, published a book. In it, she observes:

Looking back, I can see that the show might very well have sunk like a stone if, say, the Columbine massacre—in which twelve students and a teacher were shot to death by a couple of asshole seniors at a high school in Jefferson County, Colorado—had taken place the week before the show started airing instead of three months after. The audience most likely would have had no stomach for the violence of The Sopranos; people would probably have been repelled, unable to find any of it funny in the least. In that way, television is a crapshoot, dependent on the zeitgeist.

This is fascinating to read today. I can only stomach the show because I’ve seen it before, so I know what’s coming. But in the years since, we as a country have been inundated with mass shootings, some of them unabashedly racist. That the show’s characters are entrenched in white supremacist patriarchal systems for which they take no responsibility, that they are conservative Republicans without ever using the words “conservative” or “Republican,” is not surprising—it’s disturbingly common.

By the time I reach season six A, Tony is 47, the age I am as I write. From the beginning of the show, he has sought the help of Dr. Melfi for panic attacks that he later realizes have been lifelong. When I watch these attacks, they look similar to my experiences in the past year and a half with atrial fibrillation, a condition that has developed suddenly in midlife, only I don’t lose consciousness. Not yet, anyway. Dr. Melfi encourages Tony to discuss his dreams, and one of the things I appreciate most about The Sopranos is the investment in dream images and states of unconsciousness—scenes, sometimes entire episodes—that revolve around nightmares, hallucinations, visions during coma or sleep. In other episodes, I catch a couple of funny coincidences—an actor whose house we once visited with a roasted chicken when he and his wife, who is an acquaintance, welcomed a newborn; a scene where a character is wearing a Delicious Vinyl t-shirt, the label owned in part by our local pizzeria, Delicious Pizza.

In June 2020, the city of Newark took down its Christopher Columbus statue, which played a role in the episode “Christopher.” Later in the series, hilariously, the characters are indignant about the portrayal of Italian Americans in the metafictional film Cleaver made by Tony’s nephew Christopher. I’d forgotten what Christopher’s fate was. I’d also forgotten somehow that Tony, like so many Boomers, went off to the desert to take peyote. I keep thinking of the satisfaction I feel when Tony rages. I’ve been “dealing with” my own rage for quite some time, because, let me be crystal clear here: I am a rageful person. I’m aware of all the ways I’ve sublimated my rage over the years. I’m also aware of all the other sublimations or suppressions that will eventually be revealed to me over time, if I pay attention and live long enough.

But for the sake of this already seeping, spilling essay, let’s say that a particular tenor of my rage was activated when we as a country heard a candidate for president brag about grabbing pussies. In the wake of that, I and many others had to contend with unpredictable waves of rawness, vulnerability. The terms of our un-safety were writ large. To put it semi-clinically, we rode the waves of PTSD and old traumas coming to the surface with those words and the lack of action on anyone’s part. Imagine that rage compounded by the day. Some of you know.

What are all the ways I’ll eventually articulate the rage I feel in 2020? For me, the year began with rage at a publishing industry that reflects white supremacist ideals while paying lip service to watery liberal principles. It began with British tabloids creating salacious gossip about me out of a legitimate argument about how the publishing industry leaves out many voices, particularly those who are not white. Amid this rage, I’ve burned away a number of acquaintances, friends, and people I thought were allies. I have burned physical objects in the effort to manage my rage. The past couple of years, I’ve logged over 500 days of meditation, blazed through Pema Chödrön texts, borrowed books with dubious titles that claimed to offer relief from rage. Somatic work. Therapy. No therapy. Walks in the park. Cycling. Crying. So when I watch Tony Soprano rage at the minutiae of daily life, I feel a particular satisfaction and let myself sink into it, the satisfaction of seeing someone slam around their environment, breaking plaster, sweeping an arm across a cluttered desk without consequence or clean-up.

It’s been many years since I’ve thrown a full glass of water against the floor. It’s been many years since I’ve spit beer at a person who disgusted me. It’s been a few years since I had to lock my doors against a person with a knife who jumped out of their car in front of mine because we’d been road raging down Western in the blaring sun. It’s been many years since I was in a mosh pit navigating thrashing limbs. It’s been many years since I screamed at a man in our living room. It’s been many years since a man put his fist into the windshield of his car with me sitting next to him. It’s been many years since I drove with two whiskeys and three beers in me. It’s been many years since I ran from a man with a baseball bat. It’s been many years since I’ve fantasized about arson of empty buildings. It’s been years since I wore a mask and ran from police.

5

My rage, then, might come down to feeling powerless. This pandemic presses on it, a bruise that never leaves, just keeps changing color.

6

Even so, the very slow turn we are collectively making offers something of an antidote. When not watching my big screen, my small screen shows me where the protests are happening, where community care is burgeoning in the debris of late capitalism. The numbers change and we contemplate another stay-at-home order, though I have never left the first one. There are three episodes left of The Sopranos. We know how it ends. If they survived the early aughts, Tony and Carmela voted for Trump. They are hating the current look of the country. But the truth is, James Gandolfini is gone, and the smirks of sociopath Tony Soprano are a fiction I’m privileged to contemplate in the house I’m privileged to have. Our jobs keep the television on, keep take-out as an option, and pay for hypothetical future care we might need, whether because of COVID, or atrial fibrillation, or any other malady that might arise. It all feels precarious regardless.

The awareness that this sprawl must end doesn’t get me closer—in fact, I might be avoiding an “end” because this experience is not over. I mourn the diminishment of my love for the fragment. The fragment doesn’t belong here, my thoughts have been spooling for some time. When feeling strong, safe, contained, I might have a friend over to talk across the picnic table in my backyard. Every day I contemplate endings. The end of capitalism. The end of the ways we went about before. The end of things I never got to begin. If a fragment were to emerge onto the page, I might think I’m on my way back. Not to a time before, but maybe somewhere new. For now, I unspool.