When night fell on Tuesday, we knew we weren’t the only ones fully expecting to hear the blaring voice of the Emergency Broadcast Network telling us that, “Commencing at the siren, any and all crime, including murder, will be legal for 12 continuous hours. Police, fire, and emergency medical services will be unavailable until tomorrow morning at 7 a.m., when The Purge concludes.”

We didn’t get that kind of Purge, but we got something spiritually proximate: if a “purge” expels an irritant from the body by bringing it up and onto the surface to make it visible, that’s exactly what this election has done. The impurities of the American innards–its racism, its nativism, its nationalism, its violence–are once again smeared across the body politic in vivid color. The US has become a medical oddity that we’ll be studying for years to come, trying to understand what happened.

We asked several writers in the Air/Light extended family–Elda María Román, Karen Tongson, and David L. Ulin–to write brief responses to the immediate aftermath of the election.

If nothing else, we hope these reactions help you make sense of an almost inexplicable moment.

–The Air/Light Editors

NOTE: These pieces were finalized on Thursday, Nov. 5, while the races in Pennsylvania, Georgia, North Carolina, Nevada, and Arizona have yet to be called.

The Other Side: What “Build the Wall” was Really About

Elda María Román, Associate Professor of English, University of Southern California

“Build the wall” was always less about fears of Mexicans crossing over and more a general call to build a wall around white capitalist heteropatriarchy. To fortify it against threats that cultural boundaries would be breached, racial and gender hierarchies overturned.

The election results show us this red wall remains fixed, brick by brick, cemented by a whiteness living in fear and a strongman’s tricks. And when people are afraid, they lash out. For many, barriers are no longer enough, defenses aren’t enough. A country materially and socially engineered to segregate by wealth and race, to control and contain—populations in detention centers, prisons, underfunded schools, essential work that is underpaid—is not enough.

No matter the election results, the realities of this wall remain, and what scares me most, is the offensive strategies, the ones we’ve seen and those to come. Because they know, we know, that walls don’t work. There’s always a way, whether through, over, under, for people to get across, to get to the other side. They always have and always will.

What gives me hope is knowing that so many are imagining, building, and living that more equitable other side. Living an otherwise to walls. Opening confines and insisting that the past be addressed with the present, for a future that doesn’t seem scarce, and instead is realized as possible, expansive, and shared.

Red Hats

Karen Tongson, Professor of English, American Studies and Ethnicity and Gender and Sexuality Studies, University of Southern California

The red hats confused me, especially in the closing stretch of 2016 when we first began to absorb the now too-familiar spectacle of Trump accessorizing his look—an oversized, 80s power-suit meant to flatter a body stuffed with “hamberders”—with an equally ill-fitting cap. The cap promised to “Make America Great Again,” though it was probably made in China.

It took a minute for it to sink in that the red hat wasn’t just another flourish of buffoonery, but a strategic and highly effective effort to consolidate his followers under an easily recognizable sign. Appropriating the aesthetics of grassroots political movements (i.e. a shared color worn in solidarity like the ominous “black clothing” he attributes to Antifa, or the yellow worn by Corazon Aquino supporters during the 1986 People’s Power revolution in the Philippines), the red MAGA hat has come to serve the same metonymic function as all baseball caps: to reassure those who wear it that they are part of a team.

The sports metaphor is, well, more than a metaphor after four years of living under a regime during which every nuanced affect has been blunted into the thirst for winning; for winning at all costs, and by any means necessary. A brief aside that will become relevant later: I see it as all too fitting that in a country with such a crude understanding of “winners” and “losers,” the Houston Astros were never stripped of their 2017 World Series title even after they were caught cheating. For too many in the United States, the ends always justify the means.

What makes Trump’s team so loathsome to so many of us is their willingness to win like the Astros: to run roughshod over all the rules to secure the win. They take no pleasure from fair play, and follow their leader’s cues to reposition themselves as the most aggrieved, as the “victims” of fairness itself. It is little wonder that even those who have a completely different sporting ethos have been induced to go totally aggro in response to this winner take all mentality. Many of us came into this 2020 election not only wanting to win; we wanted (spoken in the ominous godlike voice of Mortal Kombat) to “FINISH HIM.”

Apropos the desire to administer a death blow on the path to victory, the gender and sexuality studies scholar, Gabriel Rosenberg (aka @bearistotle) tweeted this on election night, after it was clear there would be no decisive Biden landslide to grant us a peaceful night’s sleep:

In short: we on the opposing side want the pleasure of the red hats’ pain. We want to see them get blown out as badly as the Miami Heat were by the Lakers in Game 6 of this year’s NBA championships. The long, protracted process of democracy isn’t fun. And “winning” at democracy never feels decisive, because to be successful at it often means simply minimizing the pain—reducing the harm for as many people as possible until we can build a better world. Perhaps this is also why so many Americans can’t wrap their minds around the fact that “beating” the coronavirus, even with a vaccine, won’t look like that viral video the red hats were sharing of a Trump avatar wrestling the Rona and pinning it down in a WWE-style match. Beating the virus will, if we are lucky, be boring AF.

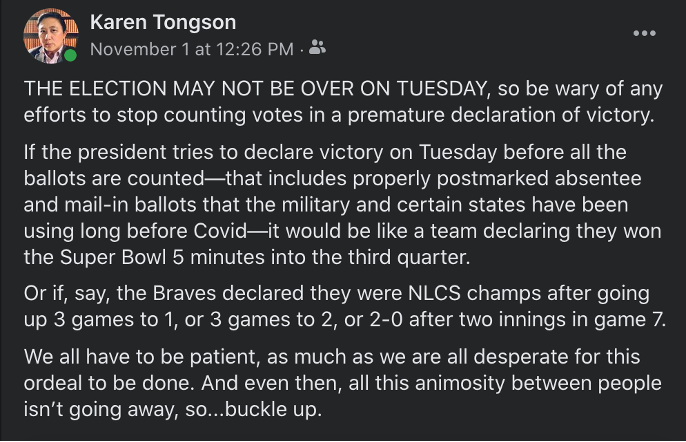

Two days before the election, I used a sports metaphor in a pedantic Facebook post reminding all my face-friends to be patient as we waited for the mail-in votes to be counted:

When I posted this, baseball was still on my brain. We were less than a week out from the 2020 World Series, when my beloved Dodgers won their first title since I was a 15-year-old band geek huddled around an A.M. radio on the Ramona High-School football field listening to Orel Hershiser record the last out in 1988. Unlike the rest of my socially distant milieu, my anxieties weren’t fully dialed into election night yet, because I’d just spent the last two weeks with my blue hat on, painstakingly enacting the ritualistic superstitions that baseball—and Dodgers baseball in particular—demanded of me. I lit sage, only ate certain foods, blessed crystals, and—depending on whether or not we won the night before—I either wore the same clothes or discarded them for luckier ones.

By stretching my sports metaphor, I’m in no way saying that a baseball game, or even a stolen World Series, are comparable to the gravity of everything we and the world have lost in the four brutal years since Trump and his red hats won. But in this strange electoral and sporting cycle, the processes of which had to be adapted because of a raging global pandemic that has killed nearly a quarter of a million Americans, I came to learn about a different way of winning.

When the Dodgers recorded the last out in the World Series, after 32 years and two gutting championship losses since 2017, the look on their faces signaled relief more than supremacy. They didn’t so much vanquish their opponents in that decisive game as they exercised their patience until an opening presented itself, which is when they went to work. They quickly racked up a few runs, then held it down, and rode it to the end.

Sometimes—especially in these times—victory is sweetest when it’s compensatory. When it comes after an excruciating wait. If we win, when we win this time, it won’t be to bring the pain, but to take it away.

THE WAITING

David L. Ulin, editor of Air/Light

I didn’t want to believe it would unfold like this. I didn’t want to believe that we would have to wait. Over the weekend, as I was looking forward — yes, forward — to Tuesday, I imagined a quick, substantial victory: 350 electoral votes, say, by 11 pm or so, a repudiation of the president, his party, and his politics, clean enough that there could be no dispute. Then the counting began, and my wife had a flash back to four years ago.

“You’re worried, aren’t you?” she asked.

I said I wasn’t, but she could see it in my eyes.

This isn’t four years ago, however … or at least, it doesn’t appear to be. 264 electoral votes and counting, according to the Wall Street Journal— a site I keep revisiting because its numbers suit me best. Wishful thinking? Perhaps, although I was never one of the former vice president’s faithful. I came to him only after he nailed down the nomination; before that, I supported a certain Massachusetts senator who always had a plan. But politics (or presidential politics), I’ve come to realize, is a matter of pragmatics first and foremost, which is what happens when you have a two-party system where each side functions as its own corporate brand.

I used to vote third party: Ed Clark in my first election, 1980; Ralph Nader in 1996 and 2000. I’ve voted for the Democratic nominee ever since. Sometimes, that’s been tough — John Kerry comes to mind. Still, if the 2000 election taught me anything, it’s that you have to win to govern (a lesson reiterated, on the most brutal terms, in 2016). This year, I would have voted for any challenger because I’m well past ready to live in a country where once more adults are in charge.

Low bar? You bet it is, but perhaps it has been ever thus. The president is not the problem; he is a symptom, and his departure will not make the problem go away. But this is grown-up time now in America, and we need the space to reckon, really reckon, with the inequity and the racism, the white supremacy that festers at our core. Just look at Tuesday’s vote as an example; in a nation where voter turnout was the highest it’s been in nearly a century, enlightenment and progressivism did not carry the day.

That’s not the fault of the progressives, but rather of a set of narratives that have long since settled into place. These are narratives of greed, of entrenchment, narratives that make too many of us see change as disruption, fear that the future is diminishing. What we need instead are narratives of generosity. Over the weekend, I allowed myself one such narrative: to believe that this might be a change election. That it didn’t happen doesn’t invalidate the wish, or reduce it to mere fantasy.

Maybe this is why, as the vote counts continue to accrue, I am allowing myself to feel a spark of hope. One step at a time, one day at a time, and if this means we have become a nation in need of recovery, then who can say that’s not the case? We’ve been gorging at trough for a long time: decades, centuries. What we require now is to reset.

This election should have been a landslide. It should have been a wave. That it wasn’t suggests the depth of what we’re facing, the divisions we may or may not be able to bridge. I’m not feeling particularly optimistic about the possibilities, but any chance we have begins right here. Not this year, this month, or this week, but this very moment, as we wait for a conclusion that should have never been in doubt.