Pola Oloixarac is an Argentine satirist, though that designation may not go far enough to capture the degree to which she dismantles her subjects. Theorist might be more appropriate, if we were to cast back to the time when theorists like Michel Foucault or Gayatri Spivak were the great disenchanters of the world.

It’s a title Oloixarac has courted in the past. Her 2007 debut, Savage Theories, is a raunchy takedown of academic self-awareness that alternates between a graduate student rewriting her elder professor’s error filled Theory of Egoic Transmissions and a conceptual artist whose work culminates in a video game based on Argentina’s dirty war that crashes Google Earth. Argentine critics thought César Aira wrote it pseudoanonymously, and were irritated when when that proved not to be the case. It was also a bestseller.

Oloixarac has spent the better part of the last decade in the United States and Mona is the synthesis of her cold observations on the literary and cultural scene here. For the purposes of a gig at Stanford, the titular character, a novelist, self-identifies as “Hispanic, Indigenous, Inca…the ideal costume for the university’s tribal masquerade. She’d been born in Peru, but claiming indigenous ancestry in any other context would have been outrageous—much like calling herself a ‘person of color’ anytime prior to her arrival in the United States.”

Mona hates the game but is good at playing it. Good enough that we find her embarking for Sweden where her novel is up for a prize funded by Alfred Nobel’s best friend. It’s a prize that could liberate her from a nebulous position in the American academy and convince her publisher to take on her ”difficult” second book.

The set up feels a bit like Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy: the prize conference is full of loquacious writer types who mourn the state of literature oblivious to their own part in its demise. A quirk of the prize setup demands that each finalist must give a talk on what his or her work contributes, the perfect frame for Oloixarac to skewer writerly pretentions A Danish-Iranian author says he is the “voice of the voiceless,” literally —his father was a deaf-mute. Another author simply plagiarizes whole passages from Malone Dies. His justification: algorithms will soon do all writing, mostly in an obsessive, recursive style reminiscent of Thomas Bernard.

Many of the writers at the conference share this preoccupation with the Internet’s eschatological effects on literature, particularly in genres such as autofiction. How can an antiquated and precious representational technology like the novel truly compete with all that the Internet generates? This is very much a current question, as embodied not only by Mona but also a pair of recent novels by Patricia Lockwood and Lauren Olyer. Those two books are concerned over the “very online experience,” however, Oloixarac wants everyone to stop worrying and love the bomb. A Colombian author in Mona argues that human authors should fashion themselves as pirates on these digital seas rather than trying to compete. In a recent essay on LitHub, Oloixarac makes a similar point, arguing that Google—which creates over 3 million pages on each of its users—is already the greatest author of autofiction. So let Google write life, she argues. The task of literature will be to overwrite it.

Mona itself isn’t particularly autofictive, though Oloixarac’s mother is Peruvian, and the author’s pen name has a faux indigenous flourish with its ‘x.’ (Her actual surname is Caracciolo.) Instead, the book recalls the alienated heroine of the type identified by Jess Bergman in the Baffler. Mona pops valium. She has rote cybersex. She relishes the hollow aerosol feel of vaping. Her editor is mortified by how dead and difficult her characters are. She has large gaps in her memory. At one point she is confronted in a sauna by her translator, whom she doesn’t recognize.

Most troubling, she doesn’t remember why she awoke at the Palo Alto Caltrain station covered in bruises before jumping her plane to Sweden. She ignores ominous text messages with a kind of dissociation that belies trauma. At the novel’s conclusion, when the repressed violence that has been blistering through the narrative bursts forth, Mona most resembles work by Ottessa Moshfegh, Catherine Lacey, or Alexandra Kleeman. Oloixarac’s move here will jar readers who have been nodding along in the nicotine haze of satire, and it may be where the novel fails as a synthesis of its many referents.

Satire is the Batman of literary genre. It breaks its subject to save it. Mona’s focus on the posturing and emotional inelasticity of contemporary literature could only come from someone who believes there could be more. Oloixarac’s ultimate belief in the potential of literature shows in an aside Mona has with a Japanese poet half way through the novel:

Shingwe, as no doubt you’ve noticed, I’m crying. I can’t tell you why, because I don’t know. I don’t know why I’m here. I only know that I am here, with you, and that I can’t write. But it’s not just that […] I don’t know what it is, but it hurts, it burns like some kind of shame, and there’s nothing I can do about it.”

Singzwe nodded. “You have a pure heart. I can see it. A pure heart is rare in the literary world.

Mona is the rage of a purist. It’s hard to like rage, though it is literally the first word in Western literature. It is, however, perhaps a welcome change, to read an author for whom writing that isn’t ecstatic may as well have been written by Google.

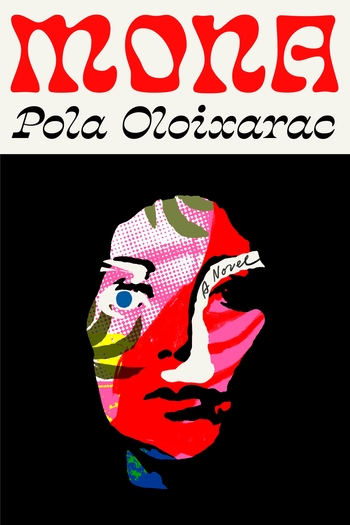

Mona

by Pola Oloixarac; translated from the Spanish by Adam Morris

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021

192 pages, $12.99