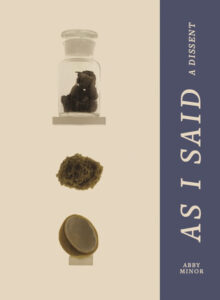

In As I Said: A Dissent (Ricochet Editions 2022), Abby Minor maps the intimate, contentious terrain of reproductive rights in the United States. The book centers around an immersive long-form documentary treatment of the life, trial, and death of Ann Lohman, an infamous 19th-century abortion provider. Framing this work, three other long poems examine what it means to exist as a Jewish woman in America, animating and interweaving three generations of voices. I was privileged to work with Abby as her editor.

Abby Minor lives in the ridges and valleys of central Pennsylvania, where she works on poems, essays, and projects exploring reproductive politics. Granddaughter of Appalachian tinkerers and Yiddish-speaking New Yorkers, she teaches poetry in her region’s low-income nursing homes and has worked as a seamstress, server, university writing instructor, produce truck driver, studio assistant, and roadie. In 2018 she was awarded Bitch Media’s Writing Fellowship in Sexual Politics. She serves on the Board of Abortion Conversation Projects, is author of the chapbooks Real Words for Inside (Gap Riot Press) and Plant Light, Dress Light (dancing girl press), and directs an arts education nonprofit called Ridgelines Language Arts.

I recently spoke with Abby about her work and process.

Erin Marie Lynch: Let’s start with the title of the book, As I Said: A Dissent, which is so direct and so sharp. The phrase “as I said” has such a range of inflections; it can signal fatigue, assertion, or annoyance. And the legal notion of dissent, of course, has long been dead center of the struggle for reproductive rights in the United States. But I’d love to hear your thoughts on dissent as a poetics, or how the notion of dissent has guided your thinking in the poems. How do the title’s two phrases collude with each other?

Abby Minor: I’ve always been drawn to the way people talk, especially vernacular speech that evolves in tandem with a culture or place. I don’t speak languages other than English, but within English there’s such a gorgeous variety of ways that people have hot-wired the language. I love the phrases we use to buy ourselves time or modulate speech–you know what I mean, as I said. At the same time, I love liturgical language, which can feel like the opposite end of the spectrum—similarly intimate, but public.

There’s a long poem in the book called “H/ours” that draws from recorded interviews with my grandmother and mom about their lives as Jewish women, as mothers, and as people who had abortions prior to Roe. Listening to those recordings, I was captivated by their voices, the vestiges of Yiddish, the numinous commonplaces. Around the same time, I read Maggie Nelson describing Alice Notley’s poems that channel voices as possessing an “unabashedly spiritual conviction that personality is primordial.” Yes, personality is primordial—it’s also public, historical, consequential. The book’s title fuses the domestic/vernacular “as I said” with a word that’s recognizably public, legal, even liturgical if we think of the law as America’s favored liturgy.

Just before the Dobbs case came down I was thinking about what I’d say to the Justices. And I realized that everything I could possibly say, I’ve already said. So there’s definitely fatigue. But also, there’s a willingness to say it again—if you preface something with “as I said,” it’s an acknowledgement that you’ve already said it and you’re saying it again, and probably will again. On a domestic level, I loved how my grandmother used that phrase to keep sort of telling the same story, or to link back to a different story—so there’s fatigue but also the idea of storytelling being ongoing.

Ultimately, I decided to call the book a dissent because I really do wish that this kind of record, this kind of language—poetry, vernacular—could matter within the realm of law and have public consequence. I think of the moment in June Jordan’s iconic 1985 essay “Nobody Mean More to Me Than You and the Future Life of Willie Jordan,” when her students are writing a letter to the Brooklyn police in response to the murder of their classmate’s brother. The students have a long conversation about whether to write the letter in Black English, the language they’ve been studying with Jordan, or in Standardized English. Although they eventually vote unanimously to “stick to the truth: Be who we been,” it’s not an easy decision. “It was heartbreaking to proceed, from that point,” Jordan writes. “Everyone in the room realized that our decision in favor of Black English had doomed our writings.”

Every time I read that essay I’m moved by the bravery of choosing speech that won’t register with those in power. And I’m inspired by those students, who decided that they had different goals, at least in that moment, than registering with power. I know it’s unlikely that As I Said will ever appear in a courtroom, but still I want to claim it as a dissent in that context.

EML: I’m really struck by that idea of choosing speech that is purposefully inaudible, unintelligible, unregistrable. I’m remembering Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s The Undercommons, and their refusal of order as “the distinction between noise and music, chatter and knowledge, pain and truth.” Could you talk a little bit about how your commitment to illegible language informed your approach to the documentary lyric—especially around the book’s distinct depictions of power and pregnability?

AM: I’ve always been more interested in energy than in skill—which isn’t to say I don’t love and learn from art that foregrounds skill or that I don’t take pleasure from exercising skill. But at the end of the day I’m attracted to poetry because it’s a place where chatter can be knowledge, and knowledge, chatter; where you can refuse that distinction, even refuse the directives many people still make—that a poem shouldn’t explain, a poem shouldn’t argue, a poem shouldn’t be left untrimmed, and so on.

Working on these poems, I struggled within several traditions, not only that of lyric poetry but also the newer tradition of abortion storytelling; in the one you’re not supposed to argue or explain, and in the other you’re sort of supposed to plead your case. I didn’t want to plead my case and I was full of explanation and argument. So in some ways the book is very veiled, in that my own abortion experience isn’t told in a straightforward way, and in other ways it’s very blunt because I wanted to see how far I could push the registers of argument and explanation in poetry and still have it feel—in the experience of writing it—like poetry.

I always felt like I was breaking one rule or another with this book. Not for the sake of rule-breaking, but because abortion and pregnancy are subjects that are so beleaguered by cliché. And to deal with that, to dodge all the clichés, I was writing to appear and disappear at once, to document and obscure, to argue and evade. The traditions and experiments of documentary poetry gave me a sense of the different paths you can take—you can take the stance of a reporter, of a photographer or filmmaker, a diarist. So rather than “do poetry” in the most skilled way, I felt authorized by the documentary tradition to seek out stances and energies I wanted to explore.

EML: As I Said is constructed wholly of long poems—perhaps the most unruly of poetic forms! I love long poems for many reasons, not least of all because they resist the algorithms and conventions favoring one-page, digestible poems that don’t take up too much room in a literary journal, culminate in a cathartic volta, can be easily screenshotted and circulated on social media, etc. How did you arrive at a book of long poems, and what were your models? What possibilities has the structure afforded you?

AM: It’s true, long poems are so unruly! I certainly felt that unruliness in writing these poems, that they were always spilling out from folders and doubling themselves and walking off in peculiar directions. I look back and I’m not quite sure how all that came together—there was a lot of doubt and grief involved, in the sense of feeling like I was just flailing among pages and pages, endless notes. I spent a lot of time writing about what I was writing, journaling about the process and the forms.

On a basic level, I think about it in terms of minimalism and maximalism—most artists tend in one direction or the other. When I first started to write poetry I wrote short lyric poems, because that’s what everyone in school was doing and that is probably a perfect form to practice prosody within that also fits the necessities of a weekly workshop. But even then there was a voice in me already trying to break into longer forms, and I sometimes felt bad about that, because we get this message that we’re supposed to cut all the fat from our poems. There’s probably a gendered thing there, too, about not wanting to take up too much space. But once I came to this insight about minimalism and maximalism—that they’re different orientations and even traditions, and that it behooves us as artists to know which tradition we’re working in—I more or less accepted that I’m a maximalist, which gave me permission to let loose not only in terms of length but also voice and form. It also helped me to understand what precedents I might look to.

I started to learn from all these wonderful books that contain long poems, like C.D. Wright’s One with Others, Khadijah Queen’s Black Peculiar, Brenda Coultas’ A Handmade Museum, Robin Coste Lewis’ Voyage of the Sable Venus, Sharon Doubiago’s Hard Country, June Jordan’s long cycles, as well as Anne Waldman and Alice Notley’s book-length poems. Seeing women writers take up so much space and deal with public subjects felt revolutionary for me, even in the 2010s! So I followed in that American, hybrid documentary vein and tried to pick up some of the possibilities afforded by longer forms—the possibility of weaving a journalistic mode with an experiential one, didacticism with obfuscation, intensity with mundanity, humor with gravity.

EML: You’re reminding me, also, of C.D. Wright’s description of her maximalist poetics: “More are welcome than can fit inside.”

Another tension in the book lies between the very, very personal and the very, very public. Abortion politics feels especially pressurized because they demand that those who have had an abortion speak publicly about something that is very intimate to their bodies and lives, and that is experienced differently by each particular body, within each particular life. Or, at the least, we have worked our way into a “national conversation” where this demand seems inescapable. How did you navigate your own poetic movements toward and away from the personal?

AM: Well the cycle that’s about my own experience is the shortest in the book and took the longest to write…six years, and it’s five pages! In some ways I wrote the entire book around the fact of that story being so hard to tell. Hard not really because it’s “hard” for me, but because, as you say, there’s this huge pressure to tell certain things, certain details—how old were you, were you partnered or not, why didn’t you want to have a baby? And I didn’t want to get stuck trying to prove anything, trying to rescue myself or anyone else from abortion stigma. Unfortunately, I do that enough in my activist life, so in my writing I wanted to do other things.

For example, to the extent that the poems navigate away from the personal, it’s because I wanted this female, “private,” domestic thing to take its rightful place on the record. To refuse to imagine abortion apart from nation; to present what’s so apparently “private” as fused with our biggest sense of what’s public. A lot of people have said the book isn’t even really about abortion, and that makes me happy. Because really it’s using the lens of abortion to look at other things: U.S. nationhood and how nation-building demands the surveillance of reproduction; what that surveillance feels like in our reproductive lives; the queerness of childlessness and non-reproductive sex; race and ethnicity in reproductive politics; the powers of the feminine void.

Ultimately I think these poems are about surrender and control, the mixture of those forces in our private and public lives. Our reproductive experiences are defined by surrender and control; as are our political lives, our spiritual lives, our creative lives. That’s why talking about “choice” in the context of pregnancy can feel off; what’s closer to the truth is that we all navigate our rights of power and surrender, and the forces of mortality and injustice, with whatever tools we have. Decisions around reproduction are intensely political, personal, mystical, and also a very mundane part of life.