These entries come from Digging to Wonderland, forthcoming from Turtle Point Press in 2022. In that otherworld between prose poem and memoir, David Trinidad chases the White Rabbit of memory further and further into the past: inside the mysteries of adolescence, childhood, and family history.

We’ll be publishing one new section of Digging to Wonderland each week from February 1 to March 1.

to be first—

the hardest thing of all

—James Krusoe

In one of the books he signed for me, he wrote, “For dear David.” So he liked me after all. That was too much to hope for, or take in: that one of my heroes could feel affection for me. And hero he was. He’d had fame, of a magnitude a poet would be a dope to hope for, in the late 1960s, with his play The Boys in the Band. The first to make homosexuals visible, multi-dimensional, real. I’d read it, and seen the movie, when I was in high school, never dreaming I would one day meet and get to know him. He was unable, with subsequent plays, to replicate his earlier success. And what was at first proclaimed a breakthrough, was later attacked (due to changing politics) for its negative portrayal of gay men. So there was a sadness about him. Ennui. A frequent impatient sigh (which I mistook for dissatisfaction with me), as if he were only just tolerating being alive. Being a survivor. He’d suffered the loss of close friends: actress Natalie Wood of drowning; Howard Jeffrey, on whom the character of Harold in The Boys in the Band was based, of AIDS. When I’d call, he’d be agitated about something on the news. “The usual ugliness,” he said. (I stole that for one of my poems.) So glamour was strictly rearview mirror. We met, as I recall, through Lypsinka, that impersonator of bygone glamour. And maintained a friendship long-distance, via the telephone. Me in New York and then Chicago, he in Los Angeles and then New York. I was respectful, careful not to trespass on his celebrity. And he (I can see now) was always kind. I kept (of course) his notes and postcards. He once sent me Celeste Holm’s autograph (when he was reading my collaborative epic about All About Eve). Once he wrote: “I so love our chats in the evenings” (further evidence that he liked me). He asked me to critique the text he was writing for the children’s book Eloise Takes a Bawth. (I can still hear him mockingly draw out the word bawth.) A section I particularly liked was nixed by illustrator Hilary Knight (who lacked camp humor): Eloise seductively reclining on the edge of her overflowing bathtub like Marilyn Monroe atop Niagara Falls in the poster for Niagara. He was funniest when his encyclopedic knowledge of the movies collided with his languid wit. Sometimes after our conversations I would jot down things he’d said. “It’s clear Achilles is as gay as a Disney cow.” (He was watching the animated Hercules on TV.) “The more things change the less they change.” (Uttered with his signature sigh.) A producer friend, Arnold Stiefel, was his “Sunday partner in boredom.” Once when I was in Los Angeles, I drove my rental car to his place on Laurel Avenue. A duplex, as I recall. Spanish style. The gate opened onto a tiled patio with hanging vines and shocking pink bougainvillea. Inside: wood ceiling beams, a sofa with wide black-and-white stripes, ornate wrought-iron staircase rail. But I romanticize. He served sparkling water with slices of lime (we were both sober). And on a Mediterranean ceramic plate: green and black olives, cheese and crackers. Behind the sofa, on a long table: several rows of photographs, in silver frames, of his famous friends: Natalie Wood, Robert Wagner, Dominick Dunne, the original cast of The Boys in the Band (most of them dead of AIDS). On a wall in the upstairs hall: a framed costume design (in muted watercolors) from Boys: the cowboy, hips cocked in a suggestive stance, thumbs in the pockets of his tight pants. I admired it when I went up to use the bathroom. He took me to dinner at a restaurant in West Hollywood. His body language changed as we walked through the door: I am someone of importance. (He had, after all, made entrances with movie stars.) I’d never seen anyone transform themselves like that. It was both impressive and gratuitous. After he moved back to New York (to the same neighborhood where Garbo lived out her later years), we talked one or two times. But then I let the friendship lapse, which, now that he’s gone, I regret.

In one of his obits online, I read that, not long before he died, when The Boys in the Band won a Tony for best revival, he said, “You have given me peace.” Too much to hope for, perhaps, but I’ll take it on faith.

The porchlight will be on, waiting for me, when I come home from babysitting. Almost every Saturday night I sit for a couple who live one street over from us, at the end of a cul-de-sac. The wife teaches ballet. The husband is handsome. They have two young girls. I am fifteen years old. I earn money babysitting (and also mow lawns) so I can buy books about the movies. The Films of Greta Garbo. The Films of Marilyn Monroe. Judy: The Films and Career of Judy Garland. The Academy Awards: A Pictorial History. The girls have Barbie dolls. I watch them play. Even pick up a doll and slip her into a dress; it’s safe, in this context. After they go to sleep, I sit in an armchair in the family room and watch Mannix on their TV. Mike Connors has dark hair and is handsome, like the husband. Then I watch Cinema 13 (on channel 13), the only place you can see adult-themed movies (albeit edited): The Pawnbroker (about a concentration camp survivor), Mondo Cane (shocking), 90° in the Shade (steamy), A Taste of Honey (about a pregnant teenager), and One Potato, Two Potato (about an interracial relationship). When the couple comes home, the husband always drives me to my house. Why? It’s only a block and a half away. The world is a dangerous place, but surely our suburb is still safe. Does his wife insist? What do we talk about, if anything, on that short drive? I can smell cigarettes, alcohol on his breath—they’ve been to a party. I look over at his profile, lit by the dashboard, framed in the window like a leading man. Houses glide past, in darkness, behind him.

Our house is yellow. The porchlight glows. The handsome husband waits for me to turn the key and go inside, before he drives off.

Over the greatness of such space

Steps must be gentle.

—Hart Crane

When my mother died in 1996, my sister handed me a bundle of letters wrapped in a white ribbon. I knew these to be my parents’ love letters, which my mother had always kept in the drawer of her bedside table. “Dad’s just going to throw them out,” Jenny said. “You should take them.” I brought them home (from California to New York), but couldn’t bear to read them. Still grieving, I was afraid they would be too intimate, that they would only bring more pain. And that they might tell me things about my parents I didn’t care to know. In 2000, when I sold my papers to Fales Library at NYU, I included the bundle of letters, still unread, still wrapped in the white ribbon. Maybe someone in the future might be interested in these, I thought, but I’ll never be able to read them. Fourteen years later, however, when I was conducting research at Fales (on Ed Smith, whose papers are also archived there), I asked to see the bundle of letters. I felt differently by then, thought that I might be able to look at them someday. I untied the white ribbon and took pictures of the letters and envelopes, but did not examine them closely. These pictures sat in a folder on the desktop of my computer for another five years, till the fall of 2019, when I read and transcribed them for the purpose of writing this. I’d always thought that the bundle included letters by both of my parents, but discovered there were only four letters from my mother to my father. (This didn’t register when I photographed them at Fales.) The letters are written in blue ink in what I’ve elsewhere called my mother’s “large, slightly loopy handwriting slanting towards the right,” on stationery with scalloped, gold-tinged edges. They tell the following story:

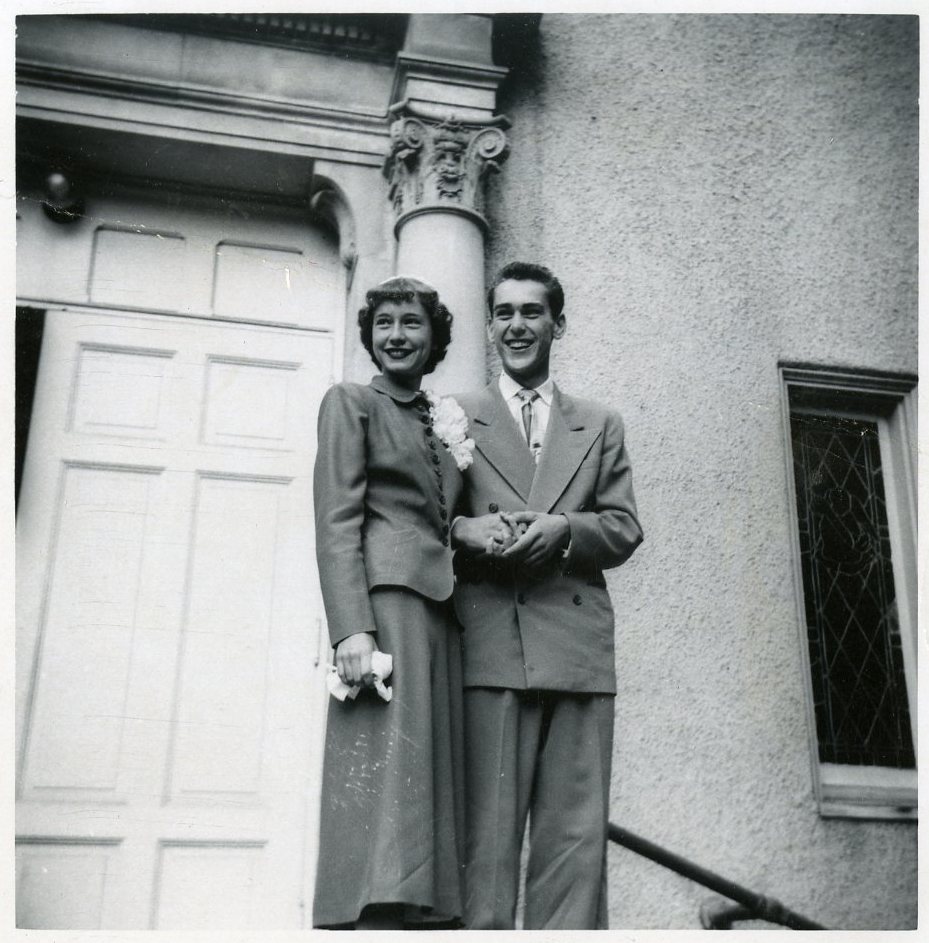

On Friday, August 4, 1950, Joyce, aged nineteen, takes an all-night train from Albuquerque, New Mexico, to Pasadena, California. She travels with her half-brother Jack, who’s eleven. Jack meets a boy his age on the train and is too wound up to sleep. He finally dozes off after eleven o’clock. But is up again at 4:30 a.m. Joyce doesn’t get much sleep. They arrive in Pasadena Saturday morning at 7:00 and are met by a man from the paint factory (a friend of her stepfather), who loans Joyce his Lincoln. They stay with their grandmother at 555 West Montecito Avenue in Sierra Madre. Joyce has been dating Rupert, an engineering student at the University of New Mexico. At 1:15 that afternoon, as her grandmother takes a nap, Joyce writes him a letter. (She will write three more over the next three days.) She is in the living room, playing records as she writes. The Lincoln, she tells him, “drives like a dream.” So far she hasn’t stalled. She asks if he’s heard the song “Count Every Star”; it fits the spot they’re in. “I could have cried when I said good-by to you at the station,” she says. “I can’t tell you enough how much I love you & wish I was in your arms.” When her grandmother wakes up, she takes her shopping in Pasadena. Her grandmother buys a rose sweater; Joyce buys a dark green sweater and “some unmentionables.” The sweater will go nicely with her new skirts. She also buys their return tickets—she can’t wait to get back to Albuquerque. Back to Rupert. Not much happens during her week-long stay; she worries that her letters are boring. Sunday morning, she accompanies her grandmother to church. (“A regular saint, don’t you think?”) She visits two girlfriends, Mabel and Marjie. Mabel has gotten married against her parents’ wishes, to an eighteen-year-old named Tom, who “doesn’t have a good job.” But they have a cute apartment; Tom is good-looking and nice. “They seemed very much in love so I pray it works out.”

Mabel and Tom, August 4, 1950

Marjie tells Joyce that three-fourths of the girls in their high school class are now married. “We decided we would be old maids forever if we couldn’t do better than marrying a ditch digger.”

Joyce and Marjie, circa 1949

On Monday, her stepfather calls to tell her he’s about to sign papers to buy a house on Hermosa Drive in Albuquerque. Joyce is happy about this, and knows Rupert will be, too. She starts getting things packed and ready to be shipped as soon as they move into the house. Her stepfather tells her that Rupert helped him out at his store—unpacking boxes of paint. “I hope you aren’t working too hard.” The next day, Tuesday, she receives a card from Rupert. “You have no idea how happy I was. I bet I’ve read it over 20 times.” She is glad to hear that Rupert is as lonely as she is. “I don’t feel so bad.”

203 Hermosa Dr. NE, Albuquerque, New Mexico, circa 1950

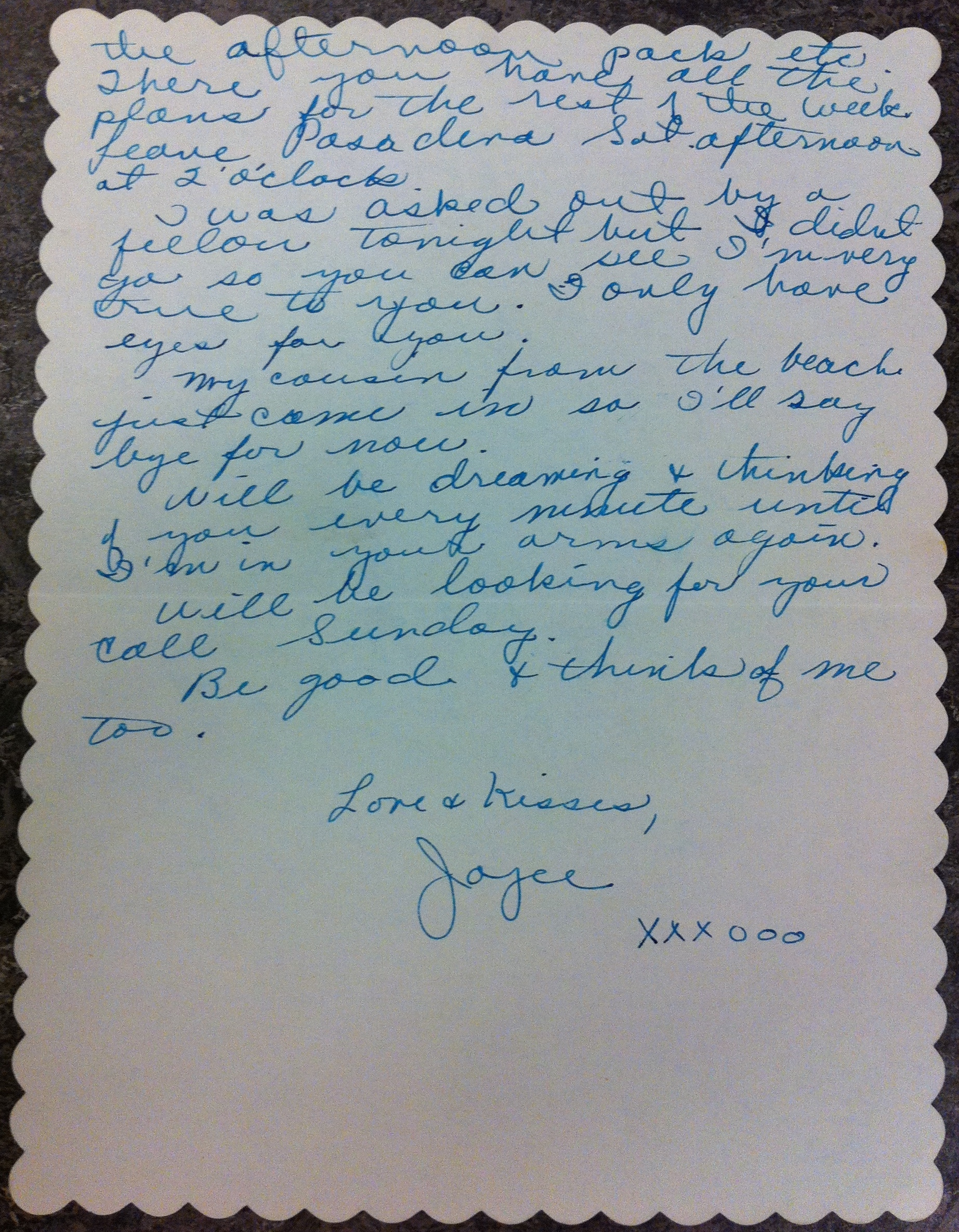

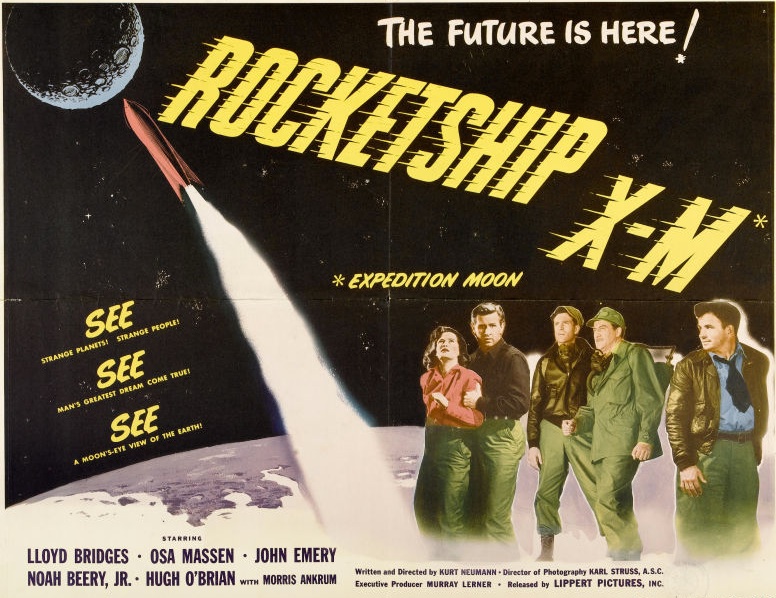

On Wednesday they have plans to go to the cemetery where Joyce’s mother and grandfather are buried. Eighty miles round trip, in the borrowed Lincoln. “Kind of dread it as it’s always so sad, but no telling when I’ll be back this way.” She wonders if Rupert has seen the movie Rocketship X-M. “Bet it was good.” A “fellow” asks her out on a date, but she refuses; she only has eyes for Rupert. “Will be dreaming & thinking of you every minute until I’m in your arms again.”

My mother's handwriting

My mother’s love letters are not boring—at least not to me. They bring her alive for a moment. A teenager listening to pop songs, shopping for a new sweater, gossiping with high school friends. And missing her boyfriend. She will attend UNM (majoring in Home Ec), but drop out after one semester—her stepfather needed help at the paint store. She and Rupert will get married in four months, on December 7, the ninth anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. My brother will be born nine months later. (It was 1950; they waited.) Then I will be born in 1953, after they move to Los Angeles, where my father will start working for Lockheed. Hard to believe I was so afraid to read these letters. Rather than uncomfortably intimate, they are simply sweet. “I’ll be so glad when I see you again. I’ll make you kiss me a million times.” I wondered why my father’s card, which she was so happy to receive, was not with her letters. My mother was so sentimental; she saved everything. I wouldn’t be surprised if the white ribbon wrapped around the letters was from one of their wedding presents. I looked up the song she mentions, “Count Every Star.” A 1950 hit by Ray Anthony and His Orchestra. Listened to it on YouTube. A lovesick crooning number. The lyrics do mirror my mother’s predicament: “Heaven knows I miss you.” And looked up Rocketship X-M. Released in May 1950, it was, according to Wikipedia, the first outer space adventure of the post-World War II era. Starring Lloyd Bridges, it tells the story of an expedition to the Moon (hence “X-M”) that goes awry; the crew ends up on Mars instead. I watched it on YouTube: pure 1950s sci-fi cheesiness. Not to mention sexism. Bridges refers to the female astronaut, Osa Massen, as “the weaker sex.” My mother’s world. Massen: “I suppose you think that women should only cook and sew and bear children.” Bridges: “Isn’t that enough?” It would take nineteen years (twice my mother’s age) for real astronauts to reach the Moon—a prospect my young parents could only imagine. I’ve always taken pride that they landed on the Moon on July 20, my sixteenth birthday.

Leaving the park, I would buy rock candy at the Candy Palace on Main Street. Last stop at the end of a long and exhausting (albeit magical) day. It came in a clear plastic box with a hinged lid and gold lettering. A little box of sweet white crystals that I could suck on the silent drive home. Over the years, I’ve collected bits of memorabilia: a map of Tom Sawyer’s Island, a wooden nickel from Frontierland, a silver Tinker Bell charm. A dozen Disneykins—I had them as a child—tiny, colorful, hand-painted figures. My favorite was Alice, in her blue dress and white pinafore. Several oversized maps of the entire park, one of which, framed, hangs in the stairway of my coach house. I pass it numerous times every day. Fantasyland was where I most wanted to be—“the happiest land of all.” I loved the Alice in Wonderland ride, though the fall down the rabbit hole wasn’t as dramatic as I would have liked. Peter Pan’s flight over London at night was always enchanting. And the part in Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride where you enter a dark tunnel and a train comes speeding toward you, always scary. Did I scream like the other children? My friend Jeffery recently told me that the Mr. Toad attraction no longer exists at the Magic Kingdom. All things must vanish, but not Mr. Toad! The merry-go-round and flying elephants were for kids. The spinning teacups could make you sick, especially if you’d eaten a tuna fish sandwich at the restaurant on Captain Hook’s ship (sponsored by Chicken of the Sea, the brand with a mermaid on the can). You could get your name stitched on a felt hat, though I never did. I envied the languid plumes that adorned them. As a child, Jeffery was terrified of going through the whale’s mouth, the portal to Storybook Land—all those miniature imaginary dwellings along a canal. “To your right are the houses of the three little pigs,” the guide “steering” the boat would announce. There was Geppetto’s workshop. And there, at the top of a hill, Cinderella’s pink castle.

I still have the little glass slipper I bought the last time I was there. Keep it in a small blue Tiffany’s box, like a piece of valuable jewelry. I regret that I gave away, in the eighties, a souvenir my brother got in Adventureland when we were young: a black plastic tiki god pendant, with two red rhinestones for eyes.

Cinderella's glass slipper

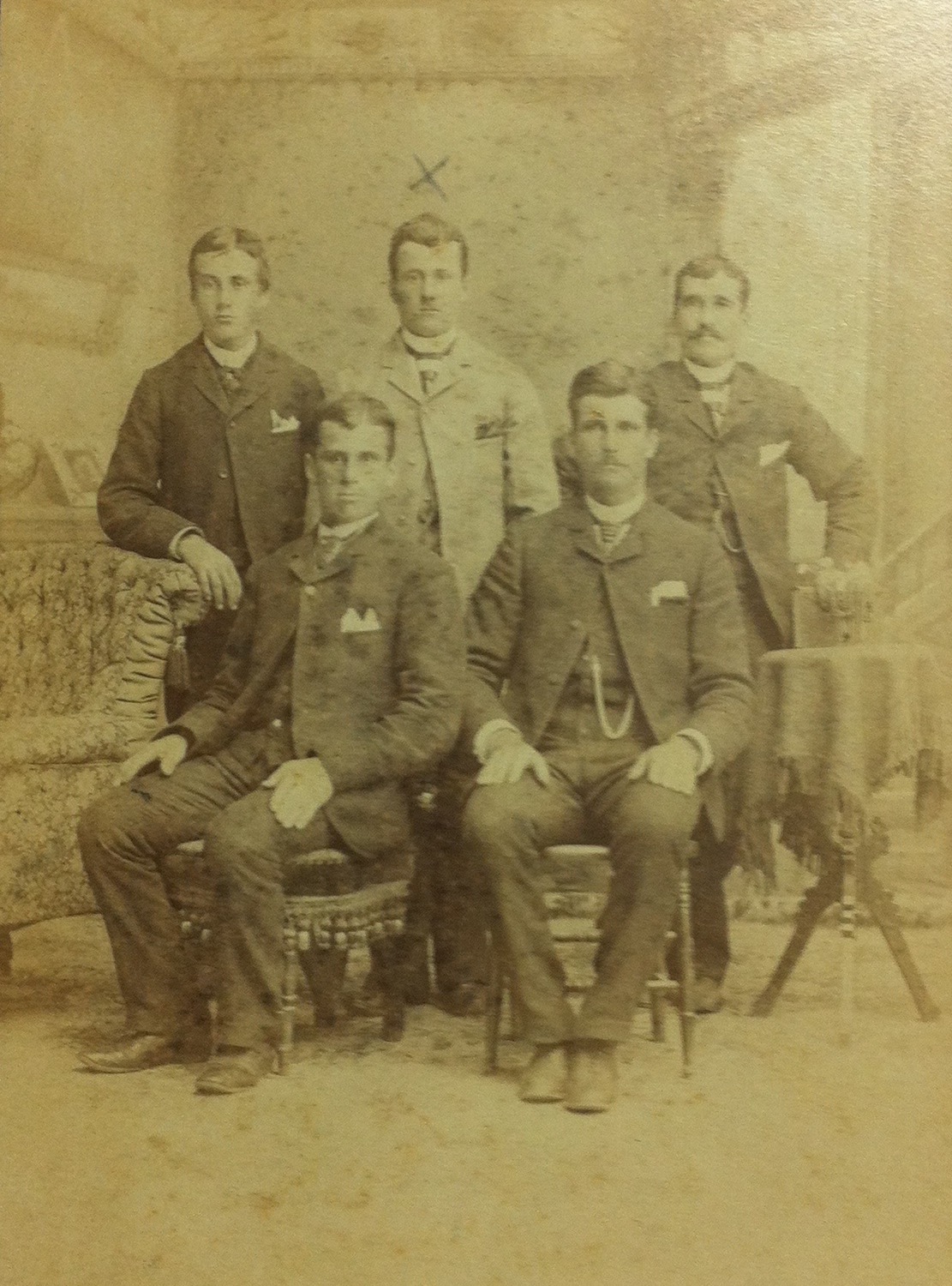

It is said that my Portuguese great-grandfather, Manuel Sousa Trindade, immigrated to the United States in the 1880s from the village of Cedros on Flores, the westernmost island in the Azores. And that one by one, he brought over four of his five younger brothers. (Nothing is known about the brother who stayed behind.) Too poor to buy his way out of the army, Manuel had been forced to spend two years in the Portuguese African colony of Angola. He wanted to spare his siblings this arduous service. Plus, Flores was a rugged island—despite its abundance of flowers. It is said that the wind blows there all the time, that the sea is stingy with its fish, and that the land yields produce stubbornly. (As a poet, I can’t help but be proud that my forebear came from an island named “Flowers.”) The five brothers settled in California, in the San Joaquin Valley, around the town of Merced. They worked on farms, plowing and planting barley and wheat; drove freight wagons; found jobs in the logging industry. (It is said that one of the brothers eventually became a “sweet potato king.”) Manuel married Louise Jacinto, who’d been born in a Mariposa gold mining camp in 1872. They moved to Oakland, had one son, Rupert Manuel, my grandfather (who was kind to me). It is said (I grew up hearing this story) that Louise changed the spelling of their name from “Trindade” to “Trinidad” because she was mad at some relatives and wanted to distinguish herself from them. My father recently told me that the real reason was convenience: “Trinidad” was a common name in the phone book, and people found the Portuguese spelling confusing. (Still, the rift makes for a more interesting anecdote.) Manuel owned a bar, but sickness (did he drink?) compelled him to sell it. He ended up sweeping gutters in Berkeley, until he fell from a truck and could no longer work. My father remembers him as lame and arthritic; he had difficulty climbing stairs. He died in 1946 at the age of eighty-nine. My father showed me a photograph (which I took a picture of) of the five brothers, taken in Merced around 1890. All of them looking very serious. And all of them seriously dressed: sack suits (with only the top button of the jacket buttoned, as was the custom), detachable starched collars and ties, watch chains draped across vests, handkerchiefs in pockets. Their well-worn shoes give them away. Manuel (with mustache) is seated in front, large hands resting on his thighs. Agostino is sitting to his right. Standing behind them: Joseph Maria, Ventura (who will die in a hunting accident; someone wrote an “X” above his head), and Antonio, the youngest, who looks like Rimbaud.

Manuel Trinidade and brothers, Merced, California, circa 1890