Last March, near dusk, I walked from my hotel on Divisadero Street in San Francisco to W.S. Di Piero’s Cole Valley flat for a warm dinner he’d prepared of chicken, potatoes, and green beans. Lots of wine.

Di Piero, who is 78, loves to cook. He tends to the doings at the oven as he does most everything: writing, reading, conversation, dancing (in his youth, he briefly pursued a career), even basketball. Intensely, studiously, joyfully.

The apartment is at the top of a small walkup, and the kitchen bay windows overlook the west side of the Sunset District. On a clear day, you can see the Pacific. The living room is lined floor to ceiling with books; there’s a computer in the kitchen, on a small desk.

It is here that Di Piero works.

We spoke for a few hours that first night and another eight hours during the following two days, including a late-night session at the Metro Hotel the night before I returned to Portland.

I’ve known Simone (as Di Piero is known to friends) for thirty years, beginning in 1993, when I studied at Stanford as a Stegner Fellow and he was my teacher. We’ve spent many hours together over the decades, and sometimes during this interview, it appeared hard to know when we were just talking, poet to poet, friend to friend, and when we were formally on task.

W.S. Di Piero was born in 1945 in Philadelphia. A poet, essayist, art critic, and translator, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2001. He traveled to Italy on a Fulbright scholarship in 1972, where he began working as a translator. A contributor to The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Poetry, Threepenny Review, and other publications, he is the author of some two dozen books of poetry, criticism, and translations. As Christian Wiman observed when Di Piero was awarded the Ruth Lilly Prize from the Poetry Foundation in 2012, “R.P. Blackmur once said that great poetry ‘adds to the stock of available reality,’ and that’s certainly true of Di Piero’s work. He wakes up the language, and in doing so wakes up his readers, whose lives are suddenly sharper and larger than they were before.”

David Biespiel: I wanted to show this to you. Poetry magazine’s golden anniversary issue of 1962.

David Biespiel: I wanted to show this to you. Poetry magazine’s golden anniversary issue of 1962.

W.S. Di Piero: You own this?

You want it? You can have it.

Where’d you get this?

I can’t remember. A used bookshop somewhere. I know that the Poetry of that era, for you, was seminal. Henry Rago was publishing a lot of West Coast writers.

Look at this! Look at this! Jim Cunningham is in this issue. And Robert Duncan and Alan Dugan. Thom [Gunn] is in this. Denise [Levertov] is in it. Merwin, of course. Merrill. Who is Rosalie Moore? “Poet as Bullfighter.” Delmore [Schwartz] is in here. “Time is the fire in which we burn.” That’s the great line of Delmore’s. Interesting, about a third of these names are gone forever.

Henry Rago, as editor, was important to you, yes? What were his editorial values, the curatorial values, that inspired your writing?

When I was eighteen years old, I subscribed to Poetry magazine. What affected me was whatever it was I found there.

Can you remember when it came in the mail what it felt like?

I didn’t quite have to hide this stuff, but it had to stay in my room. And my bedroom was small. I was also beginning to buy books with whatever money I had in my pocket back then. Poetry became part of that. It was all this protoplasmic, amorphous searching for meaning in me and a purpose in my life.

You read Denise Levertov?

I loved Denise’s work. I owned a couple of her books. When I was nineteen years old, I wrote her a letter telling her how interested I was in her poetry.

How was your relationship with her at Stanford when you two taught together?

It was collegial. Until it wasn’t. We were friendly her first couple of years. Then that friendship and collegiality thinned out. In part, because Denise would say things like, “I read this poem of yours. It’s very iambic.” Something pissy. Because she had her ideology, and it wasn’t mine. But, as a young writer in particular, I thought some of her poems were beautiful.

She was gigantic.

She was. She was everywhere. Denise could be really prepotente. She could be a bully. And if you had to work with her, you had to push back. If you pushed back, you got into a fight. So we became estranged for a number of years. Those years coincided with when I got quite sick. In 1995, I had a nervous breakdown. I didn’t know why or what was happening to me. My marriage was coming undone. I hated going to Stanford. Because it took me away from my work, and I couldn’t process any of it or deal with it. I was trying to support the family. All this other bullshit. So I broke down. I cried a lot, too much. That’s what it was like. I hope this doesn’t embarrass you, my saying this. I did seek help. I was just in a bad place, man.

If you have any consciousness left or self-reflectiveness left, you realize that you reach a point where suicidal ideation—that’s the term they like to use now—is becoming less and less ideation. Right? You start cutting on yourself. You start driving suicidally. You want to self-destruct. Well, that’s what I was. And the marriage was ending. So that was a rough ride. It took me a couple of years to get my legs under me again. Emotionally, to survive.

I came to Seattle once. I had a reading somewhere. Denise had retired to her place in Seattle. And I wanted to see her. I just wanted to talk with her. No Stanford and all that pushing and shoving. She could be so manipulative, I mean, as an academic, and she knew how to use power. She knew how to do that. And I didn’t give a shit about that stuff. She was also a public poet who very few people dared to say no to. She had a very large sense of her own importance. So, that time in Seattle, I went to her place at the lake. The first thing I remember she told me, the first thing she told me, she said, “You look different.” I said, “What’s different?” She said, “Your face is clear.” I know what she meant, because I was on the mend finally. Because I hadn’t been sick for quite a long time.

Until you get like this, you don’t understand that you have some degree of psychosis, until you get so sick that you can’t function. And, then, if you’re lucky enough to have a good doctor, the doctor tells you what it is that was going on. This required a lot of work, a lot of attention. We had a marvelous talk. We would both cringe at this notion of a healing session, because that’s not what it felt like. It was just trying to return to whatever it was we first had as just two poets.

Did you meet Robert Duncan?

Yeah. Oh, yeah.

They were close, Levertov and Duncan.

They were, until they weren’t, and then they were again.They had this big fight. If you were a poet, it passed for a public fight. Because he said things to Denise that nobody else would say. He said, you’re using politics for self-advancement. This is ideology. This does not have to do with poetry. They had one of these enormous fights. It’s all worked out in their letters. Eventually, they made their peace, as Denise eventually made her peace with Adrienne [Rich]. Because they, too, had a big falling out. It was over very similar things. When I think about Denise now, I remember that her early work was beautiful. And when I was a kid, it meant a lot to me.

What brought you to San Francisco in the late 1960s?

I was twenty-one years old. I’d never left Philadelphia. My plan was to gather my resources, whatever they were, and to leave. I had applied to San Francisco State. I wasn’t sure I was accepted. And I didn’t know how I’d pay for it. I wasn’t married yet. I wasn’t thinking about where, really, I would land or how comfortable the landing would be. I wanted out of Philadelphia. But it was also a forwarding. I wasn’t just leaving something.

Literary ambition?

It was more general than that. It was a setting out. It was a drivenness.

Were you trying to prove something to people?

I wasn’t trying to prove anything to anybody.

Did your family think you would make it?

The last thing my mother told me was that she hoped I failed and came back. Shit like that. But what are you going to do?

Coming from South Philly, that Italian neighborhood, did you move to North Beach?

I didn’t identify with that. And over the course of my writing life, I’ve had to make that decision, over and over again, when occasionally, you know, somebody pops up and says we’re making an Italian American writers anthology. I cordially decline.

This was Bishop’s position, too. She didn’t want to be in anthologies of women poets.

There you go. I wanted independence. I didn’t want either Italian Americans or non-Italian Americans to read me by referring to me as an Italian American poet. That didn’t matter. That’s what was given to me as a writer. That’s all that matters. It was given to me. But, as a representation, how I present—I don’t do that. And I wasn’t doing it then. And so I developed over the years, over a long course of years, an alertness or cautiousness toward any writer who presents as a member of a group.

So much of contemporary American poetry is X-hyphen American.

I get it. In the 1970s, after living for two years in Bologna, I came back to the United States. Although I was offered a job teaching at University of Bologna, I didn’t want it. Emotionally, I felt like an American. And I wanted to get back to my country and to write out of that. That’s the way it was.

Did you feel like you were writing as a tourist in Bologna?

Not the way we lived, my wife and I. We couldn’t afford to feel like tourists, not in the Italy of that time, the early 1970s. I want you to hear this. It’s amusing. This is not special pleading. We lived wonderfully for two years without a telephone. So, living in Bologna in the early 1970s, it was like living in the Gilded Age, when people would stop by in their carriages and leave cards, saying so-and-so will call on you at a certain time. Once a day, we would go to the local bar and buy these tokens. That’s what you needed to do to use a public telephone. Right? We lived mostly by giving English lessons. I did some commercial editorial jobs. We were flying by the seat of our pants.

Who were your teachers at San Francisco State?

There was a fiction writer there, Herbert Wilner, who took an interest in me. Herb was a pretty good writer. He was a serious man. Just full of literature, full of reading and writing. At the time, I didn’t realize that somebody was actually taking an interest in my work and in me as a writer, you know, when he would suggest things to read and he would take me to lunch and talk about stuff like that. There was also a Professor Renaker who taught Renaissance literature. I think he was bored by teaching. But that didn’t matter to me. All I needed were titles of books and the reading lists.

Where did you live?

I landed, in the first two weeks, in a hotel in the Tenderloin. Then I rented a room in someone’s house. Then I lived at three or four other addresses over the next couple of years, in the Inner Richmond, which I loved, West Portal, Eureka Valley (before it became known as the Castro), the Inner Sunset.

And you were writing poems? What motivated you?

It was passion, drivenness. That was the foundation. I was driven by aspiration and desire.

Who were you reading?

Who were you reading?

When I was still living in South Philadelphia in my mother’s house, when I was going to college, the first three books I bought were by Thom Gunn, Philip Larkin, and Laurie Lee. How weird it is to talk about this. I was eighteen years old, nineteen years old.

Laurie Lee?

Laurie Lee was as famous as the others, then.

You and Thom became friends in San Francisco. Did you ever meet Larkin?

No.

Even if I didn’t know those were the first books you bought, I’d make that connection. The other poet I don’t know, Laurie Lee. But Gunn and Larkin, in terms of all three of you possessing a high degree of comfort with making poems out of lines, that’s one place I see your poems in conversation. Another place is being concerned with precision and the peculiarity of real life. That would be, in Larkin’s case, resiliency. In Gunn’s case, a care for the erotic.

Larkin was a great poet, and I don’t like his work much. Except for maybe three or four poems.

Which ones?

“The Explosion.” It’s one of the best. One of the best poems ever. “The Whitsun Weddings” is a beauty. “Church Going” is one of the first poems I read in college.

Were you attracted to the argument of “Church Going”? The rejection and the power of faith?

I was eighteen years old. I wasn’t that sophisticated.

In “Church Going,” there’s a feigned slackness. There’s “stuff …”

… at the “holy end.”

He pronounces, “Here endeth,” too loudly. But at the end, he acknowledges the spiritual draw. That’s the Larkin move. Mock, reassess, ask what does it mean? Then, finally, come to see the world afresh. Especially in your earliest poems, you were trying to navigate that space also, sacred and secular. You’ve written that the arc of art and poetry begins in religious intensity and moves toward estrangement. That characterization is reflected in Larkin’s poems, in Gunn’s, and in yours.

Thom was an atheist. That was fundamental to him. He was a man of such expansive intelligence. He could write about religious desire, but it’s not because he shared it. “In Santa Maria del Popolo” has this quality to it.

Thom was an atheist. That was fundamental to him. He was a man of such expansive intelligence. He could write about religious desire, but it’s not because he shared it. “In Santa Maria del Popolo” has this quality to it.

Is the arc of poetry beginning in religious intensity and moving toward estrangement a fair characterization of your earliest poems?

I suppose. It’s because I was a believer when I was younger. I’ve fallen from Roman Catholicism—I’m still falling.

It’s a long way down.

Yes, it is. Then I became more of a suspecter, an inspector, of the relationship among actuality, immanence, and transcendence. That’s still true for me.

That’s still a quality of your poems.

Absolutely.

The endings of your early poems typically pivot toward the mysterious as religious expression because that is what you knew. I mean, you were young.

As I revisit those early poems, I wonder what feeling that came out of. I’m sure it came out of a feeling of: If only. If only … it was true. If only … I could make an argument against, say, Wallace Stevens in “Sunday Morning,” that heavens are imagination.

You admire Stevens, yes? And Hart Crane? Two poets for whom the medium of poetry is supreme.

I like a lot of Stevens. I love Hart Crane. And Hopkins. My feeling about them is, I don’t need to understand them. They each crafted their own expansive, musical idiom.

Keats, too.

There’s no question that Keats is everywhere in Wallace Stevens. To my mind, Hopkins is very different. He didn’t quite invent a language. But he came pretty close. And he insisted that his language was common speech. “I caught this morning morning’s minion, king- / dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding / Of the rolling level underneath him steady air …” What is he thinking!? We all develop whatever it is that sustains us in our pursuits. Pursuit is everything.

I want to ask about your family.

I want to ask about your family.

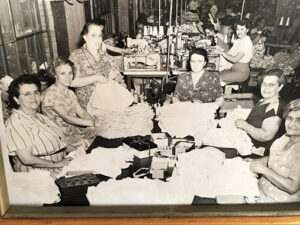

Come, look at this. [We gather around a wall of black and white photographs in the kitchen next to his desk.] See that brick facade. That’s where I was raised. That’s my grandmother. That’s her husband who died shortly after this picture was taken. That’s my father, right there. He was a babe-in-arms when they came over. That’s South Philly. [He points to another photograph on the wall.] That’s my grandmother working in a sweatshop.

Your grandparents emigrated?

Yeah. My mother’s mother was pregnant with her when they made the journey over. S, she was born just after they got here. I’m a first-and-a-half generation American.

Your grandparents came to the United States from Italy in the nineteenth century?

Your grandparents came to the United States from Italy in the nineteenth century?

No, sometime in the early twentieth century. My father’s father’s name was Aurelio. The Italian version of Aurelius. He came over first. He was in his late twenties, early thirties. It was just a standard thing. The wage earner would come first, establish himself, and migrate to a community where a lot of people looked like him, and thought like him, and could help him find a job. Then, my grandmother made the crossing. My father was a babe-in-arms. They made the journey from Abruzzo to Naples, then ship and steerage to New York. From New York, they went directly to South Philly because that’s where everybody was who came from their community.

My grandmother had two kids. When she was pregnant with her third, her husband died. She was thirty-five. So she was pregnant, the husband dies, and she doesn’t speak English. Sounds very familiar, right? She has to start to learn English, and she has to go get a job. The important thing is to get a job where people don’t speak very much English. My first lesson in Marxism was when I asked my grandmother what kind of work she did. And she said, I make bathing suits. I said, What do you mean? She said I’m a seamstress. I make bathing suits. I said, What kind? And she said, Jantzens. None of us could afford to wear Jantzens bathing suits. So here was this immigrant woman doing that kind of work.

How old were you when she died?

I was in my twenties. I had already been to Italy and back. I remember, when she was dying, she wanted to dictate letters to me for her relatives in Italy, in English, and have me translate them into Italian. Apparently, this is a common thing, that when immigrants age, even if they develop really good English, it returns. The armies come back. The armies of words. And so, I’d be talking to her in her late years, and Italian words just popped out of her mouth.

Was your grandmother devout? Where did she locate herself in Catholicism?

Everybody went to church. There was no question. Everybody. Protestants were very exotic to me. I wasn’t quite sure what a Protestant was. My grandmother came from a Roman Catholic village. They didn’t know from Judaism or Protestantism. And when they emigrated, they emigrated to neighborhoods where everybody was a Roman Catholic who looked more or less like them. Just the way it was, man.

What were the qualities, do you think, of her religious feeling? Spiritual fervor? Inner reflection?

It wasn’t fervor. I never experienced it as fervor.

Did she like the incense, the rituals, community, ceremony?

None of that. I did. The incense above all. As a kid, I didn’t give a sweet goddamn about community. But the sensuousness of High Mass, of being surrounded by all these sculptures in walls and stations of the cross? I saw suffering. You know, I was at home. On my father’s side of the family, the Di Piero side, they were quiet-spoken people. They were church-going people. They had a moral compass.

There’s a whole thing about names on that side of the family. When I went to live in Italy in 1972, the week before I left, my grandmother said, Oh, I have to tell you something before you go, because you’re going to go to Abruzzo, and you’ll meet our people. She said, they don’t know you by your name. I grew up being called Bill or Billy. When I was born, my grandmother on my father’s side, she wanted me to be named after her husband, Aurelio. And my mother said, Are you crazy? This is America. We’ll give him the American equivalent of Aurelio, which is William. But that’s not right. The English equivalent of Aurelio is Aurelius, the English equivalent of William is Gugliemo! So, my name was a mistake from the very beginning. Fortunately, as a middle name, they gave me the name of my grandfather on my mother’s side of the family, Simone. So, before I go to Italy for the first time, I’m an adult. And my grandmother says this is something you need to know. She says from the time you were born, in all my letters I’ve always referred to you as Aurelio. She says, they had no idea that you’re called either Bill or Simone. So, when I finally arrive in Abruzzo with my wife—we were young marrieds at the time, and this was real long time ago, right?—here’s this cluster of robust, beautiful people waiting for us at the train station in this remote part of Abruzzo, calling, “Aurelio! Aurelio!”

Your father was born in Abruzzo, and he came to America as an infant. He died when you were very young.

He was forty-three when he died. I was seventeen.

What is your memory of the days and months after your father died?

It was a time when, in certain cultures, if you were a teenager and you lost a parent, that’s just what is given to you. Nobody ever told me to tough it out. But nobody ever said, “You want to talk?” This isn’t special pleading. I want you to know that. And because I was seventeen years old, I never got it back then—though I have since—what it must have been like for my mother to lose her husband when she had two kids.

What images come to mind when you think about your father?

I grew up in a beer and shot culture. The men of my neighborhood, they worked jobs that they didn’t like. They were hard, dangerous, dirty jobs. And many of them, when they came back to the neighborhood, they would go to Mike’s. That was the name of the tap room on the corner. They were all Italians, except for the occasional Pole. I remember my mother saying, “Go to Mike’s. Bring your father home.” I did that quite a lot. And why would they want to come home, especially if you’re someone who, like my father, I think, was chemically given to depression and darkness? Who’d want to go home to my mother? The first thing—you walk in the door—she starts scolding you. She had her own point of view, I’m sure, her own story. But that’s not a story I can tell. I can only imagine what it must have been like for my father. The images are of a cowl. He was a sad man. He was a depressed man. He was an alcoholic. His own father died because he got sick during an influenza epidemic. What I remember is wanting to be left alone.

From both your parents?

Basically from the inherited culture. It grew into that. And, you know, it was a time when my mother would say, why don’t you go and play, go out in the street and play. And if you go out and play on the streets, then you’re going to get into trouble. On any given day, somebody was going to step in front of you and say, “What the fuck are you looking at?” What I don’t remember from my childhood, and I should, is tenderness of any kind from anybody. It’s just the way it was.

My parents were mismatched—but there was no concept, no structure for even thinking in that way. These were two really beautiful people. My father was quite a handsome man. And my mother, she was literally a pinup girl. Her picture was in the knapsacks of thousands and thousands of GIs in World War II. I don’t know how that came about. But she was one of these girls that was scouted, and they took her picture to give to GIs. If they ever wanted to look at a pretty girl, all they had to do was take this picture out and look at her. That was the grandeur that was lost in her life.

Tell me about your ancestors through your mother? Are they from Abruzzo?

No. They came from a town, a village probably, somewhere between Naples and Pompeii. They were basically Neapolitan. They were called Girone. But like so many Italians, they anglicized it by dropping the terminal vowel. They said Gee-Rhone. Girone is also the word that Dante uses for circles in Hell. Because girare, in Italian, means to turn. So girone is a path, a level, a tier. That was their name.

Do you think of who you are as what your stories are?

That’s a hard question. And the reason it’s a hard question is because it’s the ongoing task in life to try to change. Pursuing origins, if you take it seriously, is a species endeavor. I mean, it’s not just the origins of family, it’s the origins of species, and the origins of one’s own development as an artist, as a writer. I don’t want to get too intense, it’s not good for me—but, as a writer, being aware of origins of every kind, whether Abruzzo or Giacometti, is foundational.

There’s a shift in your poems over the decades, from deep musical play to expressive clarity. I would point to “Skirts and Slacks”  as the poem where the border is clearest to me. From that poem onward, your writing moves in a new, less sonic direction—not sonicless but less richly hypersonic, the old echoes from Stevens or Hopkins, Dickinson or Keats, where the medium is everything. Over the last few decades, you have treated the medium differently than you did earlier.

as the poem where the border is clearest to me. From that poem onward, your writing moves in a new, less sonic direction—not sonicless but less richly hypersonic, the old echoes from Stevens or Hopkins, Dickinson or Keats, where the medium is everything. Over the last few decades, you have treated the medium differently than you did earlier.

Yes. Beginning with the collections Shadows Burning and Skirts and Slacks, something changed. It happened when I gave myself over more, gave my work over more, to an accounting of what it feels like to be physical, to be embodied.

As opposed to, previously, what was more literary?

Yes. Earlier it was a more literary aspiration, rather than an aspiration coming from out of the body. Being cellular.

When did you acknowledge that a change occurred?

The change, I now know. We don’t know these things as we’re going through them. Maybe Yeats knew it.

But was it something you forged? Lowell forged a change in his writing from the stiff early poems to the looser iambics in Life Studies. Roethke forged a change from the Yeats-inspired rhythms of his first books to the expansiveness of The North American Sequence. You know what I’m talking about.

Yes, I do. But it was not my experience. I was engaged in a pursuit. And I was dissatisfied with the kind of poetry I had been writing, the poems that came before I wrote Shadows Burning and Skirts and Slacks. This was 1995. I was fifty years old, and I was killing myself doing it. I had a conversation with Thom about this. We were talking about early work, middle, late. This is the kind of stuff we’d talk about when we’d be having lunch, when he wasn’t talking about fucking. He was a fabulous man. He said something in passing that stopped me. He said, your early work always struck me as being symbolist. I told him, that’s the worst thing. I hate to hear that. But when you think about it? When he said it, I got it.

A younger poet is looking for hand-holds, something with authority.

You know, when you’re young, first of all, and if you’re me, you have too many other voices in the room. Biblical. Medieval. Renaissance. The whole lot of literature. Now, the voices in the room are just my select guests. That would be Keats, for aspiration and texture. And Hart Crane.

When you think of Keats, is it his sensibility that everything is in play all at once that you feel connected to? When I read your poems, I’m continuously aware that everything is perceivable all at once. Almost simultaneously, in a single poem, you could be on Downey Street in San Francisco, while there’s an overlay of a street in South Philly, and then, too, a piazza in Bologna. All at once. That’s a lyric sensibility.

That all-at-onceness is how it has lived in me. I still experience this, that everything is happening all at once. If you’re lucky, you continue to be able, just physically and mentally, to tolerate that. Because it’s painful, man. It’s overload. If I bear these kinds of recollections, whether they’re personal recollections in my life, or they’re recollections that somehow are affixed to poems that I’ve read, not to speak of the poems that I’ve written, then—and this is not a generalization—I experience it very often as pain. It’s an emotional pain.

A delight in pain? Enlightening pain? A wound?

It’s enlightening pain. But it’s also a wound because there are sources. It’s not as if one claims one’s pain because it’s a good resource for poetry. That’s not what it’s about. For me, it’s always about what has been given to me in my life and what I have lived into in my life, and all of that is: now. And that can be painful.

Has doing translation helped?

I don’t know. I do know I translated Leonardo Sinisgalli because of the plying of experiences of his work: his origins in pagan Lucania, to which he returned throughout his life, layered deep into his professional life as a graphic designer in Milan and Rome. I translated Leopardi in part to go with this consciousness of our most darkly skeptical thoughts.

In your translations, as in your poems, you’re someone who is attentive to the sonic qualities, the musicality, of language. Was that an early field of play for you as a poet?

My plan was, from the beginning, that I would be a poet who also knew how to write. Wanting to be a poet who also had some presence in the public life, even if the public life meant another language. Even if the public life meant writing reviews. When I started out, my notion was I would be able to earn a living by reading and writing. I would be able to earn enough money translating and doing literary journalism. That’s how I launched myself.

What did you take from your work as a translator into writing your poems?

A respect for the mission, a desire for clarity, a desire, which was hard for me to realize, of being in words and around words all the time.

I take that to mean a care for noticing how words and the world coincide. And yet, you know the risks that come with that. You’ve written that the danger of holding too rigorously to enthusiastic noticing is that enthusiasm, finally, will be made to do the work of the imagination. Yeats calls this the problem of the will doing the work of the imagination.

I take that to mean a care for noticing how words and the world coincide. And yet, you know the risks that come with that. You’ve written that the danger of holding too rigorously to enthusiastic noticing is that enthusiasm, finally, will be made to do the work of the imagination. Yeats calls this the problem of the will doing the work of the imagination.

Someone once asked me about what he said is an unusual degree of specificity in my poems. And my answer was the true answer. It’s that this is how I’m wired. It’s my nature. And that the details of physical reality can sometimes be difficult for me to bear.

This is what Giacometti says, too. He says, I’m not trying to make long heads. It’s just how I see them. I know Giacometti is important to you.

It all dates back to what I first saw in his statues, how he could have a vision materialized in the human. I didn’t know, at the time, any of the paintings. I came to love the paintings later.

I find the paintings more interesting.

For me, too.

To me, the paintings feel like they’re always in formation. He puts the lines in where the movement of the head sets or the eyes go, the mouth, and then he leaves them in there so that view and vision come together.

I always thought it was some kind of scarification process. Screams, scars, and then deciding the scars don’t look good. Changing them, scraping them down, until a human is going to emerge from all of these. And it was his presentation of something. I could not articulate this at the time. It was some articulation of life as passion and life considered as a suffering, that life is something we suffer, that this was the nature of us. “Speaking of Giacometti” is one of the first poems I wrote. It was about that piece called “Head on a Rod.” I had no idea why that Giacometti sculpture had such a special hold on me. I had no way to think about this stuff. All I knew was that it jumped on me and said that you need to come to some recognition, some accounting.

When you think of the process by which Giacometti worked, and what he produced, how does that relate to you in terms of, generically, the writing of poems and, personally, your own writing? How does that transfer into your work as a writer?

The way it transfers is, nothing is ever finished until your life ends.

I know you care deeply for Brancusi, too. How do those egg-shaped sculptures impress you?

Brancusi is my early poetry. Brancusi, in his way, was the anti-Giacometti. That was probably the appeal. Because his work shows no effort, except, what I learned later, after the fact, that he and his assistants, his studio assistants, they never stopped polishing those things that were finished. Brancusi was a Romanian woodworker. He made that—I don’t know what the specific title is—but that column that he built in Romania. Well, when I was first thinking about that piece of Brancusi’s, I was also reading Eliade, who was also Romanian. Eliade wrote about Brancusi’s thing, which he called “The World Tree,” because in virtually all indigenous cultures and ancient cultures, there was some figure of some kind which connected our middle earth to what was yonder. And, if it penetrated the earth, it went down to where Dante went. That was the vision, an extreme, ecstatic feeling and whatnot, a deliverance. It’s a deliverance from our mineralized, material condition. We are these animals who can aspire.

Assuming that one has certain tastes across the arts, who would be the Brancusi equivalents for you in poetry?

Oh, what a question. The closest recent poet who has something of Giacometti’s ethic about constantly working a thing is Alan Dugan. His poems are beautiful. They can be raw and gristly. He’s unafraid of extremities of feeling. And yet, there’s always this formal intelligence that’s holding it all together.

What poets come to mind—poets you care about, that is—who you would say are unafraid of extremity of feeling?

Hart Crane. Berryman, Neidecker, Plath, most recently Dugan. And for extremities of lift-off, Jerry Stern.

Your attraction to Stern surprises me. I say this as someone who has been deeply influenced by his poems and his materials. He has this pleasant rhythmicality, but not a great ear. He’s much more interested in the sentence than he is the line.

I agree. I mean, the thing about Stern is his shamelessness. His shamelessness about desire, aspiration, and ecstasy. Merwin was unafraid. I’m thinking of particular books. I’m thinking of The Lice and The Carrier of Ladders.

What about Lowell in this context?

Too willful. From beginning to end, there’s something in Lowell’s work that is willful and bullying.

Let’s change the cultural landscape. How about Miroslav Holub, Czeslaw Milosz, Joseph Brodsky, Adam Zagajewski?

Those aren’t the faraway poets that matter to me. I would replace those names with Antonio Machado, Marina Tsvetaeva, Zbigniew Herbert, Miklós Radnóti, Osip Mandelstam, and Anna Akhmatova.

These are non-Sternian poets who you just named. These are poets uninterested in the erotic or the ecstatic, although you might make the case that Machado and Mandlestam are, compared to the others.

I’m attracted to their formal fearlessness. I’d say the same about the great Lorine Neidecker: fearless, a range of effects from dry to marshy, an imperious humility. Also, she and the others didn’t have cozy groups around cheering them on with oohs and aahs.

Muriel Rukeyser?

She was a very good poet. She comes and goes in the public mind. I don’t know why that is exactly. But she comes when somebody decides to make a new anthology. Then she fades.

We were talking about the danger in enthusiastic noticing.

In the post-war period, especially with the influence of Williams, the act of noticing became so predominant in our poetry. All of us came of age under it, even if we weren’t aware. It was wired into us. That was my preoccupation. I guess the difference between a poet and other people is that a poet doesn’t let go. You’re trying to get what’s noticed and turn it into whatever equivalency you can get in words.

You don’t mean mirroring when you say equivalency?

No, no.

Dramatization? Simulation?

For me, poetry has not been the work of explanation. It’s not the work of interpretation. It’s, first and last, a work of expression.

As you think of expression, expressiveness, expressionism in visual art, what is your relationship to all that?

As you think of expression, expressiveness, expressionism in visual art, what is your relationship to all that?

One of the things about the visual arts and painting, above all, is it jumps on your nerves the way poetry does not do, because of the way poetry has to live through time—in the making of it, and the reading of it. It’s got to live in time. A picture? It jumps on you. Paul Klee’s “Fish Magic” made an impression on me when I was quite young. Another picture that made an impression on me was de Kooning’s “Door to the River.” What those pictures did, and I didn’t understand at all what was happening at the time, was it gave me a physical response because I felt like they were pushing back. They were pushing me back. It was a physical experience.

Pushing you from where to where?

From curiosity to feeling like I was being overcome by something. You see, it all goes back to Philadelphia. It all goes back to where I got my free education, which was at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Ever since those primary experiences with pictures, I’ve had the notion that I could make poems do that.

What you’re saying puts me in mind of what de Kooning might have called—is this his word?—“slipping” from one perception to another.

That is his word. He says, “slipping glimpses.”

The phrase, “slipping glimpses,” makes me think of a poem’s lyric space, where something’s happening, and then something else emerges from that. Simultaneity is a poem’s lyric space, where intensities of connections occur. It’s in the shared detailing. You say something akin to this in Mickey Rourke and the Bluebird of Happiness, when you write: “I want to say small things intensely.”

The phrase, “slipping glimpses,” makes me think of a poem’s lyric space, where something’s happening, and then something else emerges from that. Simultaneity is a poem’s lyric space, where intensities of connections occur. It’s in the shared detailing. You say something akin to this in Mickey Rourke and the Bluebird of Happiness, when you write: “I want to say small things intensely.”

I made peace with the fact that I’m a descriptive, scenic poet, and my ambition has been to be that kind of poet without being merely descriptive, merely scenic. I didn’t want to be a poet who indulges in local colorism, in “slipping glimpses.” I love those lines in Briggflatts, when Bunting is addressing Scarlatti and the sonata form, and he says one of the great things about Scarlatti is that his art shows “never a boast, or a see-here.” What I mean is, I’ve always been shy of global statements. I’ve been shy of wisdom. At some point, I thought of myself as—and this is not a very sophisticated view of what wisdom actually is—but I thought of myself as being an anti-wisdom poet. There are no generalizations. There are no global statements. All truths are local, specific to one’s experience.

What if your interest is in, say, grace?

Well, it is. There’s this poem of mine called “Some Voice.” And it’s very specific about place. It’s this tiny campo in Venice. And it has three time zones, overlapping. It’s about being in this place, and the window is open, and a voice comes out. The reason I say this is because the ending of the poem is “We take what’s given and work / with that. The rest is grace.” Both parts of that are important to me. Recognizing what the rest of it is, that’s grace, that’s mysteriousness, while also being able to live with the mystery, while you continue to interrogate it.

Related to that, you once said, “To write a poem that’s a sustained concentrate, a feeling, and that’s, at the same time, about that condition, that effort to live intensely, write intensely, and not be able to tell the difference.” That’s self-instruction, yes?

That’s a belief.

You have also written: “I wanted to write a poetry that enacted what it felt like to live in that impossible moment when a lived instant seems to recapitulate every previous instant.” To me, that is a characteristic of lyric time. When you are experiencing one occasion, multiple things or multiple occasions are also occurring vis-à-vis your consciousness, your memory, and your physical contact with the world, triggering some other connection.

Lyric time says it. My feeling about that is—and I know I’m not alone in experiencing this—it’s living with this constant feeling of all-at-onceness. Many of us live with that. It’s a condition of heightened consciousness. If you’re a poet, you choose to write out of a pursuit of recognitions. Writing is a way of continuing to try to clarify exactly what the experience is, what it has been.

I’ve been repeating to people, anyone who will listen to me, two things you say in the Mickey Rourke book about writing and rewriting. I think they’re related. One is about authenticity and artifice. The second is about revision. “If poets are artists really,” you insist, “authenticity and artifice are a single act of the imagination.”

I still believe that.

“Practice makes perfect,” you suggest. “Revision is a poet’s practice, just as musicians practice hours a day, reiterating sounds of those who have come before, been internalized, while also testing unknown chord changes, combinations, etc., while playing—as a child plays in a sandbox—over and over the sound one knows. Practice makes imperfect.” The part about revision as practice, I feel, is fantastic. I’d like to hear more about artifice and authenticity being a single imaginative act.

I can only speak for me. I’m always aware of pushing words around. Practice? I re-copy lines and poems endlessly because the repetitiveness will yield something, usually a mistake, a “moral” for a “mortal.” You knock a poem off its axis by changing “and” to a “but” or by adding or subtracting or modifying a beat.

That could be a good day’s work right there.

It’s a terrible thing to admit.

You’ve defined what you call the office of poetry as “to use shapely speech to express the radicals of existence and all their ambiguity.”

That’s right.

Also: “To answer idiosyncratically, privately, to a public world, given over to falsehood, fake facts, scuzzy rumor, casual murderousness, comedic denials, manic, vicious wind tunnel ideologies, to answer palsy language with vital language, gaiety of invention, and fabulation over opportunistic mendacity. If poetry can’t or chooses not to reveal what it feels like to live as a sentient being in a perilous enchanted world, then maybe it really is marginal or beside the point.”

I believe all that. It sounds a little strange to me. And it is political. Though I’m not a topical poet.

Would you say you’re a poet of class consciousness? What has been your interrogation of class?

First of all, I’ve never made a big deal of it. But I have never shed my identity to myself. It’s not something I talk about. I don’t try to make a fuss about it. But I remember my origins. My origins are still in me. I’m still a union man. This is visceral. This isn’t intellectual. I distrust management of virtually every kind. I distrust landlords and deans. Anybody in a position of power, I distrust. Stanford was the last place I ever should have been. Took me awhile to understand why I was getting so fucked up when I was there. This new book I have in manuscript is called Burning Money. So, class, yeah. I’ve written out of a class concern that’s been internalized. And then, if I internalize it, I know it’s going to surge when I’m writing poems. I don’t have to present it. It’s just going to show up. It saturates your being.

You’ve written: “Poets aren’t aware of their astonishment in the presence of reality until they’ve written out the astonishment.”

Sometimes, I’m aware of living in an occasion that might be an occasion for poetry. It doesn’t often happen that way. I’ve never been the kind of poet who thinks—the first time I heard this phrase it just made my skin crawl—of getting a poem out of an experience. Right? There’s a cynicism so deep into that it’s just unacceptable. But, sometimes, I do have that feeling. It’s an indulgence in mystery and a pursuit of clarification at the same time. It can be a very painful condition to live with. The process of the work, sometimes, forces me to get preoccupied about things. And recently one of my preoccupations has been wonder, the fact of wonderment, and awe. And how fine it would be to write out of my deepest sense of wonder of existence. The density of existence, the densities of consciousness without saying that’s what it is.

When you describe moving toward wonder, I’m reminded of something else of yours, a bit of a longer passage: “A tradition in Abruzzo, where my father was born, was to take a newborn after it has been washed and wrapped and set it down on the earth so that it touches its first mother and its soul is grounded. I like to think my father was thus grounded, though I have no proof he was. Born here instead of over there, I should have been made to touch the ground. It might have helped me mineralize the vapors of imagination.” Will you talk about what you mean, to mineralize the vapors of imagination?

Mineralizing really means to keep moving towards something that’s solid, weighted, textured. Everything we associate with material reality, with the fastness of things, you know.

It reminds me of this, also by you: “Coleridge, mad dog of discriminations and divisiveness suffered the differences among things: ‘Sea, hill, and wood, / This populous village! Sea, and hill, and wood, / With all the numberless goings-on of life, / Inaudible as dreams!’ He suffered most the abyss separating nature from consciousness. Wordsworth is the surveyor of things come together and mutual blessing. He views consciousness. He doesn’t suffer it.” That’s so right, by the way! And then, this: “He’s quick to admit strangers to his banquet. Coleridge must first question any stranger about his origins and destination and means of travel. Then he goes back to the kitchen to revise the evening’s menu.” Which are you?

I guess I’m closer to Coleridge than to Wordsworth. It has to do with a preoccupation with the particulars of existence and separating them out so that a poem becomes an occasion for bringing them together, for making a pattern out of them. Coleridge seems to me to be more honest about his feelings. He’s less extravagant and grandiose when speaking of a life of feeling than Wordsworth is. Coleridge is closer to physical reality.

What part of the preface to the 1795 edition of Lyrical Ballads do you feel is Wordsworth’s mind and what part is Coleridge’s?

I think whatever is interested in separating one thing out from another, anything that’s analytical, that’s Coleridge. When it has to do with synthesizing and gathering, accumulating, collecting, recollecting, that’s obviously Wordsworth. I just wonder what kind of conversations they had because Coleridge was, you know, an exhausting talker. He would just wear people out.

That’s what Keats says in his Letters. It’s an interesting divide, a Coleridge vein and a Wordsworth vein, two kinds of Romantic thinking for poets writing in English: the tactile and analytic, to use your terms, and the mutual blessing of synthesis. Then, modernism takes place and disrupts everything. What would you say modernism’s relationship is to those two veins?

Modernism probably owes more to Wordsworth than to Coleridge.

One outcome of Wordsworth’s continuous wavelengths, the going outward, is the eventual fracturing and slippages that are the imaginative foundations of modernism.

My head just now started spinning off into how important Browning was to those early twnetieth century modernist poets, too, and how alive the dramatic monologue was, and the appeal of that particular kind of psychic migration. And how, of all the practices that carried over from the nineteenth century to the twentieth century, dramatic monologue is the one most in disrepute now. My favorite lines in all of Browning are from “Fra Lippo Lippi.” You know the poem. He says that what he learned in his life is “This world’s no blot for us, / Nor blank; it means intensely, and means good: / To find its meaning is my meat and drink.” The power of those lines, emotionally, they get to me. The forthrightness of it. You pursue the things of the world. I do more pursuing the things of the world than I do in pursuing things of other worlds, the otherworldly. Now, that’s the kind of pursuit that has given us some of our greatest poetry. But it has not been the kind of poetry that I’ve written because, at some point, I became too skeptical of religious belief, skeptical of faith of just about any kind, for good or ill.

I have a formulation about the arc of your writing. I’d call these braided arcs. There’s the arc from writing poems with a literary basis of perception to, in your more newest poems, simply trying to represent the world as it comes to you. Also, I think there was, at one time in your poems, a reliance on Catholic religious resonance. I don’t mean that as totally artificial, just that was the vocabulary at hand. And that language of Catholic feeling often reveals itself near the ends of those early poems. The more recent poems don’t require that but have found the spirit-resonance in things and in the relationships between you and those things. Finally, I would say the earlier poems tend toward “sensation and force,” to borrow a phrase of yours, while the later poems act more like a gathering of the materials that are present and trying to put them in relationship to each other. If I had to pick one poem where the switch takes place, it would be “Skirts and Slacks.” That poem marks a change, so far, ever after.

Your characterization is a fair one. I knew when I wrote that poem, and poems that immediately started to issue after that one, that I had found something new for me. Mostly in how much less I needed to say. How much more important it was to be as exact, as physical, and not to assume that my aspirations carry over into adequate expression. If you don’t have the means to do that, then aspiration simply sounds like heavy breathing of over-enthusiastic religiosity, because, literally, the grounding isn’t quite there.

In my reading, there is a precursor poem to “Skirts and Slacks” that bridges these two eras: “Shrine with Flowers.”

I knew that’s the poem you’d single out. I knew it. That’s how it happened. I found things in the writing of that poem, “Shrine with Flowers,” that I did not know I had to say. I was punching through to things formally that I knew for me were new and useful and instrumental.

To read “Shrine with Flowers” in the sequence of your poems is like coming upon the end of a literary hill, and then, after that, it’s a more naturalistic terrain. The way you handle the whole metaphor of the illness of the neighbor, Louisa, and, because there are two homes in that poem, by studying one home you are also revealing something going on in the other …

…and the garden and the racoons…

…and the neighbors, the garden, the house, the illness, the marriage—all that is presented, segmented, and sequenced in a way that one thing opens or slips into another, and the intricacies aren’t neglected.

That’s all accurate. They establish a field of meaning, a pattern of relatedness. I was also writing that poem when my marriage was breaking up.

Linkage is everything.

Linkage is everything. Yes, that’s true.

What about your poem “The Depot?” Formally, at least, it behaves not like a sequence but a series, an overlap.

It’s like a transparency. It’s like two imaginations being on top of each other. That’s the thing about the imagined waitress in that poem.

“The Depot” leads to “Blue Moon,” the Halloween poem that begins, “They’re gathering now / cone-head ghouls Spider-Man / fly-by-nighters’ burnt-cork cheeks …”

That’s a post-9/11 poem.

The way “Blue Moon” shifts in the bottom half is similar to the way “The Depot” shifts.

But the feeling tone is very different at the end of each of those poems.

I mean, the overlapping consciousness is similar.

We’re back at that conversation about all-at-onceness. If you take two things happening in two time zones, then it’s only in what you’re calling lyric time, lyric space, that you can do this. Because that’s what we do. Poets are not analysts. They’re synthesizers. One of my intellectual interests, preoccupations, for years, has been neuroscience. As I read more about it, as I live more, and as I continue these fruitless interrogations of what might or might not be a transcendent order, and if so, how can it be transcendent if it’s immanent? I mean, this is the kind of thing you start going around and around. The brain has produced the most fabulous imagined states of being for centuries and centuries. Fifteen or twenty years ago, I started reading Antonio Damasio’s books and other neuroscience books. Only later did I realize that, without knowing I had such an interest, I was reading all of Oliver Sacks’s books. And then I started reading about memory as a kind of brain circuitry, memory as physical organic reality.

As in dialects of a memory?

In place of dialect, I’d say idiolect. I love that word. I got it from my friend J.T. Barbarese. I didn’t know what it meant. The word turned up in a letter. It’s something person-specific. Language can be a person-specific thing—as dialect is a culture-specific thing. Any poet who merits re-reading has a distinct idiolect. Ammons does. Schuyler is this way. The idiolect is some kind of emotional, psychological signature. It’s only yours.

I got an email today from this friend of mine, and he had read some of my new things, and he wrote back to me. And he just quotes some phrases. He quotes lines from a poem I wrote about Nat Turner. The line is: “stout angels black and white hacked each other.” He quotes from a poem about Hopper, the painter: “Windows inflect an ethic of the washed” and also “the average, creamy, bumpy wet light.” That’s me! Never too many adjectives! Never. And what I’m going to say from now on is what he calls my work: “Di Piero’s tide pool life.” That’s it. And why is that accurate? Because it goes to my feeling for wanting to get everything in without doing it in a way anywhere close to what Whitman did to get everything in.

You once said to me, decades ago, that the way you can tell one poet from another is by the imprint of their consciousness, the imprint of their mind.

I still believe that. I confess to having borrowed the language of that from Henry James. What James said his fiction had to do with is—and the phrase is—“the moist, moral impress one consciousness makes on another.” That’s a fiction writer’s rendering of something similar to what I’m saying there. I do think that, with the good ones, if you put three, four lines of a particular kind of stanza in front of somebody, they will identify the sound and discern which poet is which. It’s like listening to Coltrane. You know the sound.

You can’t mistake a line of blank verse by Wallace Stevens for a line of blank verse by Robert Frost.

If you’re an artist, you’re an artifice-er. You cultivate many things at once. I have. I’ve cultivated a complete sluttishness of consciousness. Anything goes. Everything can be thought. Let everything through.