I submit, below, a manuscript for our consideration titled “Introduction to New Hires.” I’m not sure what the document is—maybe we can call it an unfinished pamphlet. It’s something my father wrote, or had been tasked to write, but never finished, at a job he was fired from three days after he started it.

I found “Introduction to New Hires” in a box of writing my father, Eddie, left behind when he died. He was not a career writer. He was unpublished except for a single piece in The Philadelphia Inquirer about a vacation spoiled by a hurricane: “Better Safe Than Soggy.” The same box also contained his unpublished voodoo novel, titled Daddy’s Little Doll (I never read it), his unpublished memoir that doubled as a takedown of the Catholic Church (I read this; various angry notes and attempts to beat the church at its own logic), and numerous family eulogies (he wrote eulogies for each of my mother’s deceased family members, which—I found out later—he’d forced on everyone as the self-appointed “family eulogist”).

I’d never seen the manuscript before, but the story around it had become a thing of legend to me. On the one hand, it was the most banal piece of writing he’d ever done, and yet his passionate attachment to its construction got him fired from the best job opportunity he’d ever had. He’d spent most of his working life as a night shift mailroom worker at a major investment firm. And he hated it. Hated it. This pamphlet-writing job was his opportunity to get out, but he was fired before the end of his first week because, as he told it, he fought for his vision that “Introduction to New Hires” be written in a way that was unlike any other pamphlet that had ever come before it.

*

It all started when, after nearly twenty years in the mailroom, someone from management in the Communications Department noticed that Eddie was a smart guy and a good communicator. This manager said, “We gotta get you out of this mailroom, I’ll find you something.” And soon enough, Eddie was brought into the Communications Department for a chance at a 9-to-5 office job—not only that, but a job as a writer. For his entire life, Eddie had wanted to be recognized as a writer, “a published author” as he called it, but he never knew how to make it happen. With this opportunity, he felt his time had finally come.

My mom took him suit shopping. They bought five suits. She had them pressed. She ironed all his shirts. And like a well-trained 1950s-era American Girl, she also ironed all his socks and underwear. By the time his new job started, he had a week’s worth of complete outfits ready to go.

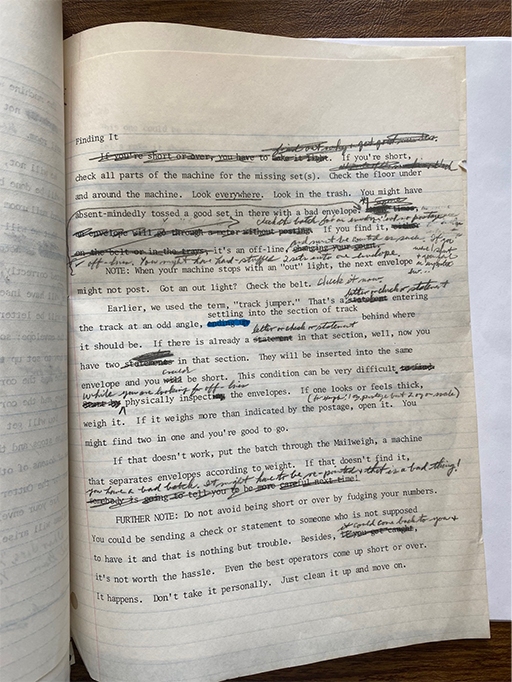

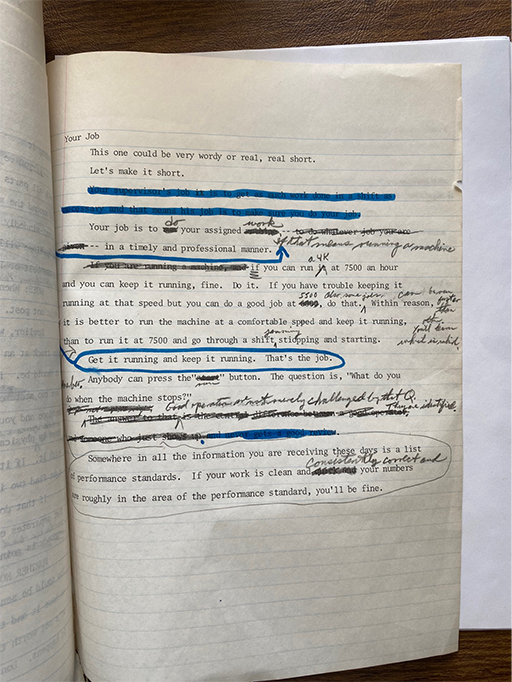

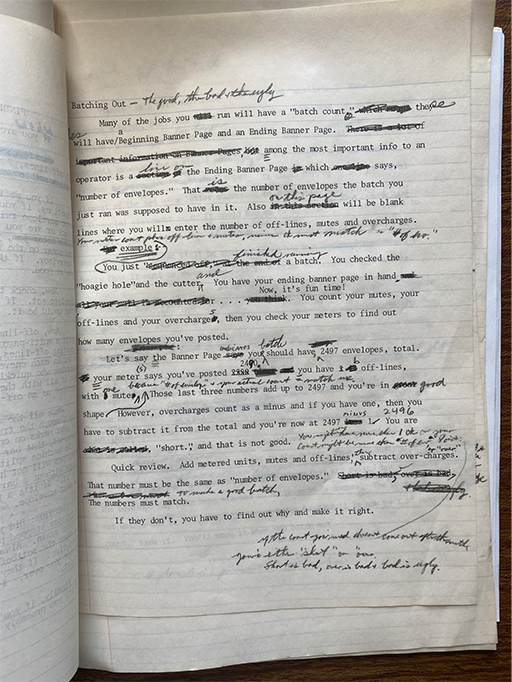

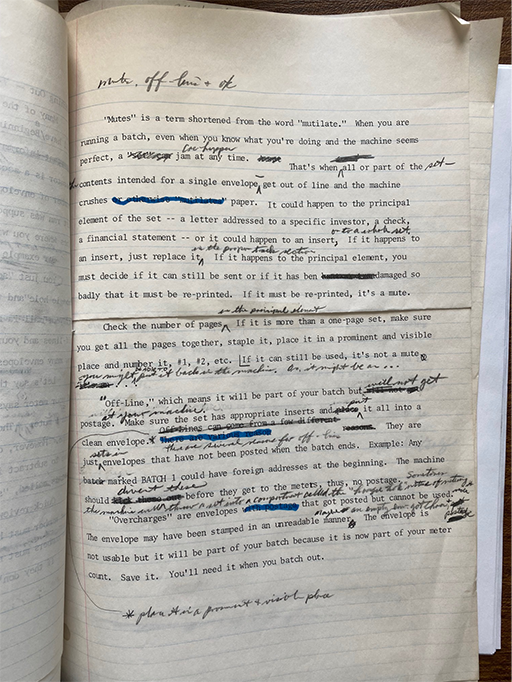

On day one, he was given his task: write an introduction to new hires in the mailroom. He was given earlier manuals to use as guides. He was instructed to keep it basic, informational.

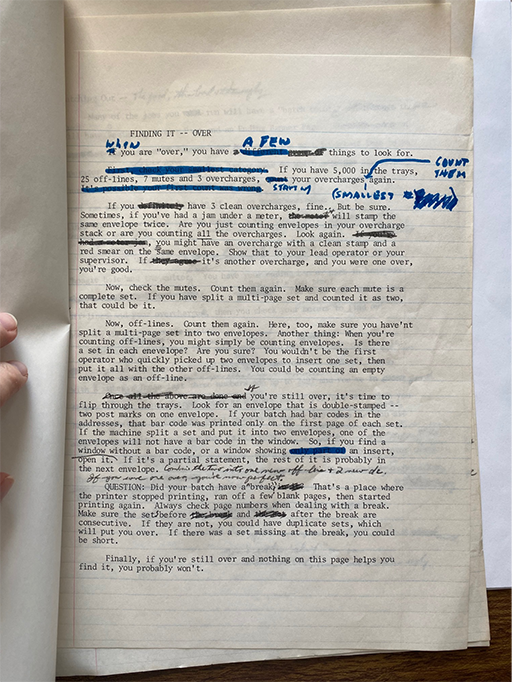

He wrote his first draft. And he did it his way. He felt he needed to invent a new way to write an instructional pamphlet; necessary, he explained, because the examples he had been given were too dry. He wanted to really speak to these new hires, but also to innovate, and make it entertaining to read.

He also refused to use a computer, and instead brought his old typewriter to work. He line-edited things by hand. He assured the manager that he’d enter it into a computer when it was done.

The manager rejected the first draft, told him he was getting too into it, that it was just a pamphlet. Try not to take it too personally, Ed, the manager told him, it’s just a generic introduction to the job, nothing to lose sleep over.

But Eddie wasn’t about to waste an opportunity to lose sleep.

“No,” he insisted, “this is your introduction of the company to new hires! Don’t you want them to think that you are the best, that we are the best, that you hire the best writers who take writing seriously, who innovate, I mean, isn’t it right there in the name of the company? Vanguard? We tell everyone we are out ahead of the others, we do things differently here. Don’t you want to show them that?”

I know my father’s temper well. I imagine him sitting across from his new boss, end-gaining off the edge of a cheap office chair, red-faced and getting belligerent about it. I imagine his manager finding it all a bit odd.

“Just write the manual, Ed.”

But Eddie was determined to prove the boss wrong. He spent the next few days working tirelessly on the manuscript. He brought it home at night. He skipped his TV shows. He ate dinner at the typewriter. And every morning, his drafts were rejected. He skipped breaks, worked through lunch, and tried new angles and approaches. But every afternoon, he was rejected just the same. Twice per day, for three days straight, he was told no, that they just wanted him to write a basic, ordinary instruction manual. And every day, twice per day, Eddie refused.

Before the week was over, Eddie was sent back down the mailroom. He didn’t even get through all five of his new suits.

*

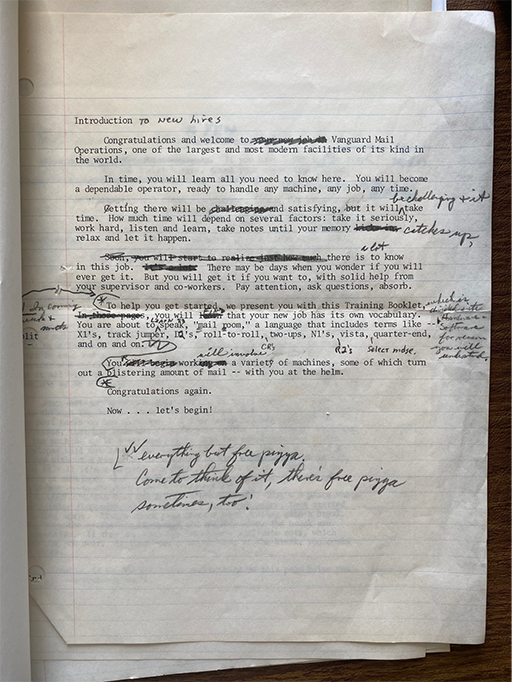

I learned all of this from my mother, who told me the story as it unfolded. The only time Eddie ever discussed it with me, he referred to one segment where he notes, in his characteristic angular handwriting, an idea for a joke he might include: “Everything but free pizza. Come to think of it, there’s free pizza sometimes, too!” He said he fought hard for these lines. His point was that this thing needed humor. Management disagreed and found it not only unnecessary but not actually that funny. If there’s pizza sometimes, why keep the line “Everything except free pizza”? In a pamphlet where the aim is to keep it brief and informative, a line that is about to be revealed as false should simply be erased.

But in Eddie’s mind, this was solid gold comedy and the boss was an idiot.

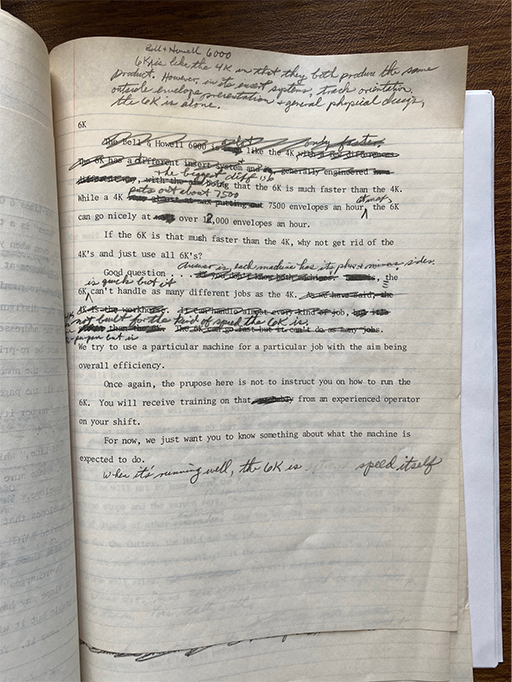

While humor was important to Eddie’s vision for the pamphlet, the real star of “Introduction to New Hires” is The Bell & Howell 6000 which, my father wrote, is “speed itself.” This piqued my curiosity, so I googled “Bell & Howell 6000 + speed.” The BH 6000, or BH6K to those in the business, sorts 12,000 envelopes per hour and in its time was the fastest mail sorting machine in history. My father worked 40 hours a week, so that’s 480,000 envelopes per week, which is 25,000,000 envelopes a year. He worked there for 23 years, so that’s 575,000,000 envelopes processed by Eddie. Is processing mailers for a huge investment firm a kind of writing?

DATE OF FIRST USE 1995-09-20

™ EXPIRED 2020-05-01

SN 75-114,469 BELL & HOWELL MAIL PROCESSING

SYSTEMS COMPANY, DURHAM, NC FILED 6-5-1996

BH 6000

FOR MAIL PROCESSING MACHINES (U.S. CLS. 13, 19.

21. 23, 31, 34 AND 35).

HRST USE 9-20-1995; IN COMMERCE 9-20-1995.

I talked about the pamphlet with my friend, the artist and writer Alejandro Crawford, who was doing a job that involved drawing 3D digital schematics of machines. He suggested he could try to create a model of what the 6K might have looked like, if I could get him some information about its design or inner workings. So I called the sales and marketing departments at the firm to see if they had images of it, but they didn’t. I tried to find a company archivist, but there wasn’t one. I even asked the nice person who helped me process Eddie’s death paperwork at the firm’s HR Department. She knew of the machine, but had no further information.

I called various departments at the firm and tried everything from being honest that I was writing about my father to making up stories like “Hi, I am a tech reporter writing about the history of mail sorting machines and need information about the BH 6000, as it was a huge innovation. I seek patent or trademark documents, images of the BH 6000 or design diagrams, archival records, or contact with someone who would have such documentation.”

But there is absolutely no record of the BH 6000 at the firm except that everyone seems to know it is a machine they once used and no longer use, and that it was once “a big deal.” There are no images of the BH 6000, no pamphlets, no instruction manuals. The firm’s new mail operations division uses different machines now.

*

My mom, Eileen, grew up as a fairly sheltered girl who liked to have fun. She married Eddie expecting to be a stay-at-home mom and the wife of a writer/editor, which is what Eddie had imagined for himself. But it didn’t work out that way. By the time I was eight, she was the one working and he stayed at home—but without taking over the cooking, cleaning, or childcare. She still did all those things, too.

She was from a solid, kind, wholesome family. She was the oldest daughter of eight children and most of her siblings have multiple children. More of a traditional Irish clann than simply a family, there are about seventy-five of us. Every weekend there’s a christening, a communion, a graduation, a wedding, or a funeral. We do everything together.

My parents grew up a few blocks from each other, in Mayfair, the Irish Catholic neighborhood in Northeast Philadelphia where our whole family is from. My mom had known Eddie since kindergarten, including his abusive hateful mom, his silent ghostly dad, his lovely and hilariously disassociated sister, and a brother he became estranged from.

My mom was part of a standard-issue late-fifties high school girls’ club, the kind of thing that looked, in movies like Grease, like a gang. But my mom’s “gang” was a gang of “good girls.” They called themselves “The Checkers.” Their motto was—and I am serious—“fun, but not too fun. And everyone knew exactly what it meant,” my mother proudly declared. They were fun party girls, a guaranteed good time always, but they weren’t letting you do more than kiss! They kept it “in check.” Hence, “The Checkers.”

*

My father didn’t start working at the investment firm until after I went to college. About a week after I left, my mother gave Eddie an ultimatum: either get a job and start helping around the house or I am leaving you. She was able to get him to agree to dust, vacuum, and do the dishes. But on the question of taking an office job, he was stubborn. She could only convince him to try temping. “Temporary” was the only kind of job he was willing to take. He could not face the idea of himself as anything but a published author or a big-time editor. Since neither of those things was happening, he became a temp. Ironically enough, he quickly found a somewhat permanent gig, where he was still a temp but they needed him all the time. For ten years, he worked the night shift in the mailroom, but for temp wages, with no health insurance and no retirement plan.

Then one day, my mother found out that this large investment firm paid full-time mailroom workers fairly well and provided them amazing benefits: a generous 401K, long paid vacations, a life insurance policy, secondary health insurance during retirement, and hundreds of thousands of dollars automatically placed in a health saving account. She was beyond infuriated when she found this out; she was disgusted that they could have been collecting on this the whole time. She confronted him and, after a long and wrangling battle, forced him to accept that he did, in fact, work in a mailroom, and that after a decade of working there for a pittance, he needed to accept the pay and benefits that came with the full time job. He had to do it, or—this was her second such ultimatum that I am aware of—she would leave him.

He did it.

It turned out that the main thing holding him back had been that as a temp, he did not have to wear the polyester mailroom worker uniform. He just hated the idea of the uniform. He said it was like “a confession of failure.”

*

Alejandro’s idea to design a BH 6000 still seemed interesting to me. Recreating it felt like an homage to labor. We can ask questions about the place of this machine in the economy—the investment firm’s mail sorting machine, infernally bound to the constantly churning financial market—and the person who must sacrifice nighttime sleep to work it.

Since I got nowhere with the firm, I began writing to everyone I could at Bell and Howell. But no matter what I wrote or who I pretended to be, I got the same reply:

Thank you for your inquiry. The BH 6000 was a Bell and Howell inserter introduced around the early to mid 90’s and was the fastest inserter of its kind at the time. However, we discontinued this product and have no information to share with you.

You can find the current listing of Production Mail equipment on our website at https://go.pardot.com/e/138131/production-mail-solutions-/2qz12p/247992038?h=FuxFYJinP1t87T4wjIspOPVQTbu5MMRpUlfGco8GUTA

Thank you,

The Bell and Howell Team

I contacted the lawyer who oversaw the trademark, but he didn’t have images of the BH 6000, either, and had nothing much to add.

I searched for patents. Through this, I realized that the BH 6000 is not so much an object, a thing, but a union of various gears, switches, cranks, funnels, and levers, put together in a sort of way that stuffed and moved envelopes really fast by 1995 standards. Like an industrial Ship of Theseus, the patent might not be for “the machine,” but for its various parts, each with their own separate patents, and each infinitely replaceable.

By now, the BH 6000 has evaporated from history, in part because it barely existed as a unity in the first place.

*

I had imagined the 6K like the Star Wars Imperial Star Destroyer: sleek, metal, pointed, thousands of tiny black windows conveying information. I imagined it defying human perception of time and space.

I imagine my father, standing at its side, rocking slightly back and forth, focused but in an altered state, some mix of tired and wired; one with the machine, absorbed in its codes, its sounds, ready to respond to its incessant need for more paper, more envelopes. He occasionally moves to the output end to lift the box where the finished jobs fall and pile up, a box that will be taken away by someone with a different job, the mailroom box carrier job.

Recently, my friend, the poet Eddie Hopely, also fascinated by dead media, searched for the 6K while in Rome and found an image. The image didn’t live up to what I had imagined. The copy machine at my job—at an austerity-bound community college—looks more space age than the 6K, which you can see incorporates a block of wood.

*

Shortly after taking the full time job, Eddie became obsessed with the firm’s founder and CEO. He read the CEO’s autobiography and talked about it constantly, for years. He also drank the wine from the CEO’s winery. He loved to open it, let it breathe, pour a small amount in a glass, swirl it around, smell it, take a sip, and say, “Oak.” He regularly reminded us of the heroism and genius of this CEO. It was strange. But we let him do it.

“As long as he stays employed,” my mother said, “he can like whatever he wants.”

*

After my parents died, in the process of cleaning up their house and going through all their old things, I kept finding trophies from the firm, countless clear acrylic fake crystal trophies of various shapes and sizes: globes, pyramids, cubes, bowls, all with the firm’s logo, a date, and some text naming whatever the occasion was. Things like “$500 Billion Milestone” or “Mutual Fund $1 Trillion.” These were never personal trophies except for the occasional “X-Year Anniversary” or the final “In Honor of Your Retirement.” None ever had my father’s name on it.

After what felt like a lifetime of listening to my father rave on about the glory of the CEO whose mailroom he operated, I felt a bitter hatred for these fake bullshit “trophies.” I threw each one in the garbage as I found it. Looking for silverware in the dining room, I found another drawer full of trophies; lifting the fake flower wreath out of the glass bowl centerpiece, I realized it read “Quarter End Record Broken” at the bottom, in a circle around the company logo. There must have been a hundred of these things crowding my parents’ little townhouse. Why do the mailroom workers need a fake glass pyramid reminding them the firm just made a trillion dollars? Once I realized the sheer volume of them, I wished I’d piled them all up and taken a photo of them and then melted them in a bonfire on the CEO’s lawn.

In the end, I saved one as a memento. It sits on my desk as I write this.

My father was proud of these pathetic little trophies. But all they said to me was that he had been hoodwinked. How many people are hoodwinked into worshiping a small group of super-wealthy people who earn their fortunes on the backs of the workers, workers who have real gifts but no real time or opportunity to develop them? The firm wouldn’t be so rich without the mailroom, and the firm wouldn’t be so rich if people weren’t forced to gamble their retirements on the stock market. But here, enjoy this fake crystal trophy, night shift worker, and please remember to buy a copy of the CEO’s ghost-written autobiography, too. Maybe you’ll learn a thing or two about hard work.

Then again, maybe the firm was just deeply invested in the acrylics market.

*

One way Eddie handled the humiliation of working in the mailroom was to tell everyone he knew that he worked “in communications.”

“Technically true,” he’d always say to my mother and me. “I have a gift. And that gift is communication. The mailroom is beneath me. I don’t know why I am there, or how this happened, so I will not allow it to be how I am seen. That’s not me. I am the guy who has a job in communications. And it just so happens that the mailroom is part of the communications department, so, technically, I do work in communications. I don’t think anyone needs to know that my part is sorting the mail.”

His strange relationship to the truth was part of his Irish inheritance. He had a gift my Irish therapist calls “The Blarney.” Not all Irish people have it, but it has something to do with the Irish way of storytelling—a gift for generating eloquent speech, including making shit up out of whole cloth when necessary, sometimes getting the truth confused, or getting carried away with talk, or maybe just being full of shit. Eddie’s mastery of The Blarney was possibly part of his creativity, but it also really sucked sometimes.

In 2004, at a Christmas gathering of “friends” from his youth, Eddie, fronting as an executive in communications, decided his “go to” conversation topic would be the wonderful new invention, track changes. Unfortunately for him, the party was full of successful, real executives who had been using track changes since the 1980s. Eddie, however, had only just learned about it and so imagined it was new. He kept describing how to use it in detail, as if no one at the party had yet encountered it.

“Have you heard about track changes?” he’d ask.

And the person he was speaking to would respond half-seriously, “Sure, yeah,” as if the question was rhetorical and leading to something greater.

But it wasn’t.

Eddie would then launch into his routine no matter how anyone responded: “Track changes is this thing you can click on and it will keep track of different changes or deletions you make to a specific document. You can actually see, people can comment or suggest changes and you can accept them or delete them! It records all the changes and suggestions, and you can even restore things. You can change something and then undo it!”

My mother and I had to sit by and smile, gritting our teeth through the low-key horror.

It was painful and humiliating to watch the looks come over people’s faces as they realized what was happening. And of course, these people—people who had “made it” in the gross 1980s American Wall Street sense—were the inspiration for his need to lie in the first place. He cared so much what they thought of him. Everyone had “made it” but him. By their silent smirks, I knew that they found his humiliation entertaining. They just let him keep going, and when given any space to do so at all, Eddie always kept going.

*

Since my father’s retirement, the mail operations department has closed down, and the firm outsourced all mail services to a large mail sorting company in El Paso that uses the labor of day workers from Mexico.

A Reddit-style discussion board for people involved in the firm offers pages and pages of speculation about the outsourcing, everything from opinions about the company using labor from Ciudad Juárez to the idea that Texas’s lower humidity, compared to swampy southeastern Pennsylvania, might allow mail sorting to move faster by keeping envelopes from sticking together. I found out that all those great benefits that came with the job when my father worked it no longer exist.

*

My father was King of the Bullshitters. He raised me on the old Irish adage: Never let the facts get in the way of the truth, and never let the truth get in the way of a good story. Perhaps these are the rules of The Blarney: it’s a hierarchy where facts are lowest, story is highest, and truth is somewhere in the middle. He lived by this. I was raised to think of the truth through a storytelling lens. This meant the “truth” was less about a moral calculation or a strict accounting of fact-on-fact, and more about what my words cause a listener to imagine and feel in their heart, and a desire to connect and be accepted socially.

The storyteller’s work, as I understood it, was to tell the story that gets to the heart. If the facts don’t give the feeling of the experience, then we reshape, remix, resize those facts. You may need to twist something to drive home a point, use hyperbole, create incredible images—many effects can work towards creating the truth. It’s about the listener’s feeling matching the feeling of the experience that led to the story. This roundabout path, the theory says, cuts to the heart of the matter more than facts do.

But I’ve had to unlearn a fair amount of what I learned from Eddie on truth. Too often he took it, I think, too far. But also, as his primary pupil, I’ve sometimes taken it too far. Because I believed this was how it worked. The biggest lies I ever told were sincere efforts to point to my most inexplicable truths. Sometimes this worked out, other times it ruined relationships.

For most of my life, I believed it was totally okay to say I was “from” any area of Philadelphia that I had ever lived in, if it had made a deep impression on me. Certain places have, I feel, entered my DNA. I take places into me; I learn them forever; they rewrite me. I’ve told people I was from Mayfair, Kensington, West Philly, and Norristown, because each of those places marked me deeply. But I re-mixed the facts in a style I learned from Eddie: I told Norristown stories as if they happened in Kensington, I told Kensington stories mixed with Norristown stories as if they happened in West Philly. All of it felt true when I said it. Some of it still does. But I understand many comrades believe that where one is “from” needs to be something like the address your parents filed taxes from for more than ten consecutive years of your life before the age of eighteen. I get it.

Where I’m from can’t be where my grandmother kept me and my cousins loved me; it can’t be where I felt safe and where I belonged; it can’t be where I spent a year doing meth to avoid remembering what happened, gradually reducing myself to a skeleton; it can’t be where I learned people can live happily and functionally as anarchists in squats, and I never felt more liberated; it can only be the place I lived the longest before the age of eighteen, even though I reject it, because it rejected me, and good riddance, because its haunted ancestry has nothing to do with mine, and never did, and never will, and so I long repudiated it and excised it from the depth of my being. But yes, it must be that one, the place where the worst things happened; yes, that is where I am doomed to be “from.” And so I feel as if I am from nowhere in the end. I abdicate all my seats, afloat forever, odd of orbit, like Pluto: a raging half-planet no one can pin down.

For a while, in response to all this, I became a truth purist. A fact checker, a side-eyer of others’ wavering half-truths. But I learned that this, also, does not work. Everyone lies, almost constantly. Language doesn’t tell the truth; as Vico says, it is used to “make truth.” The poet George Oppen says “truth is the pursuit of it”—the pursuit, a process. You can write your truth one day, then return to it the next day and find it lacking. You remember what happened but your brother remembers it differently. You tell someone your story, then they retell it incorrectly at your funeral. In the end, many aspects of Eddie’s theory of truth bear out. People tell you what’s true for them. Or what they’ve decided to believe. Or the version of the past that will make you see them the way they want to be seen today, because it feels true to who they are today, however metaphorically.

Nonetheless, I now suffer from a hyper-vigilance around my every speech act. Is this true? Am I sure? Am I deluded right now? Am I nervously overcompensating? Meanwhile, I’ve converted my blarney skills into becoming a fiction writer. All my stories are remixes of facts, with various amounts of fabrication thrown in. Whether I’m great at fiction writing or not is beside the point, I was born for it. My truth is fiction.

I’ve come to believe Eddie’s self-mythologizing—and my own, by extension—ultimately derives from a long lineage of ancestral trauma. We are Irish; the Brits cut their colonizer teeth on us. It’s not just about Eddie refusing to admit his position in life. It’s also about the need to hide weaknesses, to avoid being discarded by family and society, a desperate need to fit in, a bid for validation and connection with others, and for survival. It’s wanting to be seen and valued, but not looked at too closely; to share (and shed) certain feelings without being compelled to directly repeat the worst of what has happened to you; to suggest the worst of what has happened to you without having to recount it; and to suture one’s broken self back to the human group by trying to make oneself understood, by presenting the world with a version of yourself that you hope will track. Self-mythologizing is an act of defense through translation, telling stories as directions for how you want to be viewed, a cover for the rejected misfit in you, written by that misfit, however desperately or deludedly.

I don’t mean to pin these issues to an ethnicity; these problems are ultimately human. But I can see The Blarney as a survival strategy, a way of fast-talking to get oneself out of trouble that stems from colonial oppression. And it’s easy to see how this could evolve into a way to talk one’s way through situations of shame and anxiety. It operates on the assumption that social life is less about having one’s facts in order than it is about being preoccupied with, maybe even lost in, maps of human desire, obsession with belonging, looking for little signs of connection, knowing perception and language for the labile systems they are, and expressing oneself accordingly.

Once in my teens, I got myself in trouble by revealing facts about myself to cops who had arrested me. My father was not mad that I’d done something illegal, he was angry—and didn’t speak to me for three days—because I had not come up with a story good enough to get myself out of trouble. He admired my friend Denise for denying the wine cooler in her hand was hers.

“At least she tried,” he said.

I, foolishly, took a swig of my wine cooler and told the cops they were overreacting. That got me handcuffed. Lesson learned.

There is an ethics here, one that is easy to miss if you have a more puritanical, more actuarial take on life and language. The Irish don’t simply lie, as WASP culture has historically loved to say. In my upbringing, it was repeated often that you should never lie about your feelings, never pretend to be someone’s friend if you’re not, never share others’ secrets, and never break a promise. You had to be a person of your word in that regard, and emotionally honest always, at all costs, especially within your own community.

My father said often, with a stern austerity, sometimes even grabbing me by the arm, “Tell the facts when it’s important,” which, he explained, was when there are consequences that could materially affect people in a negative way. Then, to the best of your knowledge, you give the facts.

But otherwise, language is a creative art. For things like dealing with authorities who can harm you, or when trying to make the feeling of something understood, facts are labile, and are often not the truth. Facts never equal the suffering and wonder of the real story.