I’ve never lived in Gardena, “Freeway City,” a community south of downtown near the on- and off-ramps of the 110, 91, and 405. I did not spend much time there as a child. My neighborhood sat at the base of the purple San Gabriel Mountains in Altadena. Early memories include being carted through crowded Japanese markets around vats of radishes pickled in stinky fermented miso.

My first full introduction to Gardena came in my early twenties, after I began working for The Rafu Shimpo, a historic Japanese American daily newspaper, founded in 1903 in Little Tokyo. Reporting on the community, I found comfort in Gardena’s small ranch homes arranged in a grid on numbered streets, reminiscent of a Monopoly board with single houses on each property. In contrast, the commercial areas of Pasadena were on the verge of a complete makeover. Developers eventually swept away antique stores and tiny Japanese markets on listless blocks of Old Pasadena to make room for a Tiffany outlet, a Cheesecake Factory, and numerous chain clothing stores. Gardena, on the other hand—aside from the swapping out of one of its ubiquitous card clubs for a monstrous Hustler Casino—largely looks the same now as it did in the 1980s.

Gardena is home to a number of seminal Japanese American cultural and faith institutions. Its psychic umbilical cord connects people like me to our community lifeblood. There is political representation: In 1972, Ken Nakaoka became mayor of Gardena, the first Japanese American to be elected to lead an American city in the West. And there is economic development: Not only did Japanese car companies—Toyota, Honda, Nissan—make their first American corporate home in Gardena, but so did Japanese American businesses like Mikasa, launched by George Aratani after his release from Gila River concentration camp and a stint with the Military Intelligence Service in Minneapolis.

Gardena in the 1970s and 1980s seemed like its own ethnic island, a place of folklore. The typical Gardena Sansei girl, this Pasadena girl imagined, fastened slivers of scotch tape over her eyes to create double eyelids. This same Gardena girl inspired Sansei young men from Northern California to drive more than three hundred miles in search of romance.

Wealthier Japanese Americans have since decamped to Torrance or Rancho Palos Verdes. But some of the community’s younger middle and working class, many of them artists, have slowly moved back into neat and more affordable (by Los Angeles standards) apartments and ranch homes, some owned by their grandparents or parents.

There’s always a party in Gardena; even the municipal events are reminiscent of backyard celebrations. City Hall will host a wine and cigar festival followed by a pet adoption the following weekend. There are ice cream socials, a koi show, heritage festivals, and annual holiday events.

My collaborator, Edwin Ushiro, moved to Gardena a few years ago from Culver City because he and his wife Lynn wanted to be close to her 100-year-old grandmother. Gardena has that small-town feeling without being so remote, writes Edwin, who is renowned for his dreamlike illustrations of his native Maui. Gardena feels like Hawai‘i, only a Hawai‘i in the 1990s.

In contrast to credit card-only transactions in Culver City eateries, Edwin found himself going down the Gardena rabbit-hole. In line at a local market, he was ushered in front of two seniors who were writing checks and didn’t want him to have to wait for them. At Meiji Tofu, an artisan-level, non-GMO tofu maker on Western Avenue, the cashier wrote his first name on a piece of paper and said that he could pay later after Edwin discovered that he had no cash on him. (Being a dutiful Maui boy, he of course went immediately to an ATM and returned to pay a few minutes later.) Then, he stopped by Sakae Sushi, the beloved takeout-only spot. His jaw dropped when he saw the cash-only sign.

There’s absolutely no place like Gardena in the continental United States with its legacy Japanese American food. No matter what new pop-ups or food trucks emerge in gentrifying neighborhoods, nothing can replicate what has taken root in a valley that once was the fertile host to strawberry fields.

*

Gabrielino Indians and then settlers, part of the Rancho San Pedro land grant, were the first to come to Gardena Valley. They were followed by Chinese agricultural laborers. At the turn of the twentieth century, the Japanese immigrants arrived, who grew strawberries in Gardena and adjacent Moneta and Strawberry Park, areas later absorbed within the city’s official borderlines.

Strawberries, a labor intensive crop back then as well as now, require workers with skilled hands and sturdy bodies to stoop down and pluck the red fruit from vines planted on elevated beds. The Japanese were good with their hands, it was said. We played into the stereotype because why not? Both men and women labored in the fields, sometimes even on Sundays, causing white Protestants to protest that this disregard for the Sabbath and gender roles gave the Japanese an unfair advantage. For the Issei and Nisei, the concern was for economic survival and also family.

You didn’t need much acreage to eke out a living with strawberries—this was a perfect crop for Japanese immigrants who didn’t have much capital but did have a built-in labor force. My father was part of this strawberry legacy. Not in Gardena, but in his birthplace in Watsonville, part of John Steinbeck’s Salad Bowl. After being relocated to his parents’ native Hiroshima when he was about three years old, he returned to Watsonville in his late teens, after World War II. He went to Texas to pick tomatoes as a migrant farm worker, then returned to Watsonville to tie up asparagus and work in an apple dehydrating plant. It was only a matter of time before he turned to strawberries. Strawberry tenant farming sustained him and his older brothers as they acclimated to post-World War II American life. Just like the fruit that they picked, my father and an uncle moved from one location to another before ending up in Southern California.

*

Being the child of people raised in Japan meant my Saturdays were spent at a Kyodo System Japanese language school. I, like my classmates, held two identities. During the week at public school, I was a dutiful student, maintaining close to a straight A average. But on Saturdays, this facade melted away, revealing my other more notorious self, a hell raiser and regular cheater. That week’s assigned kanji, complicated Chinese characters, were written on the underside of my forearm or on scraps of paper hidden in pockets, which I brought out during weekly quizzes. It made sense that we young Japanese Americans were revolting at this effort to infuse in us the exact culture that the larger society told us was a source of shame.

Gardena had at least two Japanese schools, one connected to the Gardena Buddhist Church. Most dreaded were Japanese speech contests, in which I couldn’t remember what came next in my memorized speech. I had no choice but to stumble forward. Yet even as I shamed my family, I learned an important lesson. You won’t die if you make a blunder on stage.

Beyond the speech contests, the undokai, athletic competitions, were the most F.O.B. (Fresh Off the Boat) activity in which I participated. What made the Japanese school experience so unpalatable was the way it imported Japanese cultural practices into my teenage American life. Saturday language school began with students lined up in a grid for “Radio Taiso,” a Japanese national calisthenics routine that continues to be followed in schools and workplaces. Imagine my surprise, during a Zoom for artists sponsored by the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center in the early months of the pandemic, when a young community activist led us in a session of “Radio Taiso” in our chairs at home. The sing-song recording no longer provoked the same pang of embarrassment. Moving my body together with others—no matter how separated we were geographically—provided a brief physical and psychological relief from the isolation we were experiencing.

While I sometimes resented the undokai activities—the wearing of red or white hachimaki around our foreheads to identify which team we were competing for—I did relish the picnic food. My mother and other Japanese immigrant women were the original reusing queens, holding to the principle of “mottanai,” or “don’t waste [anything].”

Broadway and Bullock’s square, embossed boxes were repurposed and lined with wax paper to hold perfect rectangles of onigiri, rice balls wrapped in black dried seaweed, or makizushi, rolled vegetable sushi, colorful with tamago-yaki (a type of egg omelet), blanched spinach, and kanpyō, brown strings of shredded calabash gourd. Certain triangular onigiri contained the embedded treasure of a red pickled plum, salty enough to serve as a semi-preservative. Those boxes of rice balls were prepared and brought to undokais, kenjinkai (prefectural) and gardener picnics.

The distribution of door prizes was a necessary practice of such gatherings. I won my first door prize at a gardener picnic. I can still remember that flush of excitement, going forward with my winning ticket. I didn’t care that my prize was a clear plastic trash can. I proudly placed it in my room next to the desk that my father had built for me.

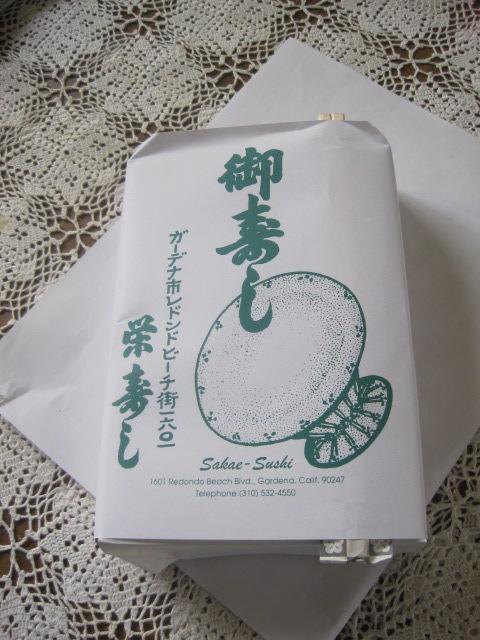

For all of these reasons, Sakae Sushi is the heart of Gardena. It’s take-out only and, as mentioned, cash only, thank you. Before the pandemic, you could peruse the menu inside a small room where old People magazines were lined up on a table for those waiting to pick up their orders. Most offerings are vegetarian, including the type of makizushi served at undokais and community picnics. There are also what Japanese Americans call “footballs”: inarizushi, deep-fried soybean pockets that are simmered in broth before they are stuffed with rice. You can choose both seafood and egg options; most reminiscent of country life are the marinated saba (mackerel) nigirizushi. I travel back to the days when Fish Harbor on Terminal Island was full of Wakayama immigrant fishermen when I take a bite of those salty silver fish slices over a ball of vinegar rice.

For Edwin, Sakae Sushi connected him to his hometown in Maui. On one of his early visits, he encountered Emi Tani Castillo, part of Sakae Sushi’s new generation. She picked up on his pidgin and asked if he was from Hawai‘i. As it turned out, she was related to a Maui family, one of whom had been Edwin’s old friend from Boy Scout days. Every holiday season, the family travels to Gardena to help Sakae Sushi with its overwhelming New Year’s Day orders (comparable to the demand for tamales for Christmas). These things don’t surprise me anymore, he says. While turning a corner on the streets of Gardena, he may be bumping into ghosts that have traveled across the Pacific Ocean.

Both Edwin and I agree that Sakae’s presentation of the sushi is exquisite. The pieces are arranged in a cardboard box lined with wax paper, just as it’s been done by families for decades, and then wrapped with paper featuring the store logo in green. It’s a masterpiece of presentation and taste, all for under ten dollars. In an era where we idolize scarcity, I value the accessibility of Sakae Sushi’s beauty and deliciousness. Even though the pandemic has necessitated certain changes—call-in orders are now requested and pick-up is from the back, through a plexiglass window—it’s still cash only and the food is thankfully the same.

*

Gardena is working class, which reminds us of our roots, whether that means the sugar plantations of Hawai‘i or the gardening routes of people like my father, dressed in a white T-shirt, jeans, work boots, and a baseball hat. The city is more ethnically diverse now, with Black and Brown families living in apartments and those single family, detached homes.

The community has a notorious side with its history of card clubs and burlesque shows, now eclipsed by Larry Flynt’s Hustler Casino, which dominates one of the main thoroughfares, Redondo Beach Boulevard. For decades, Gardena had a monopoly on poker clubs in Southern California, despite constant efforts by disapproving residents to shut them down. Then in the 1960s, neighboring cities such as Bell Gardens and Hawaiian Gardens legalized card clubs, which led to the closure of many historic ones in Gardena.

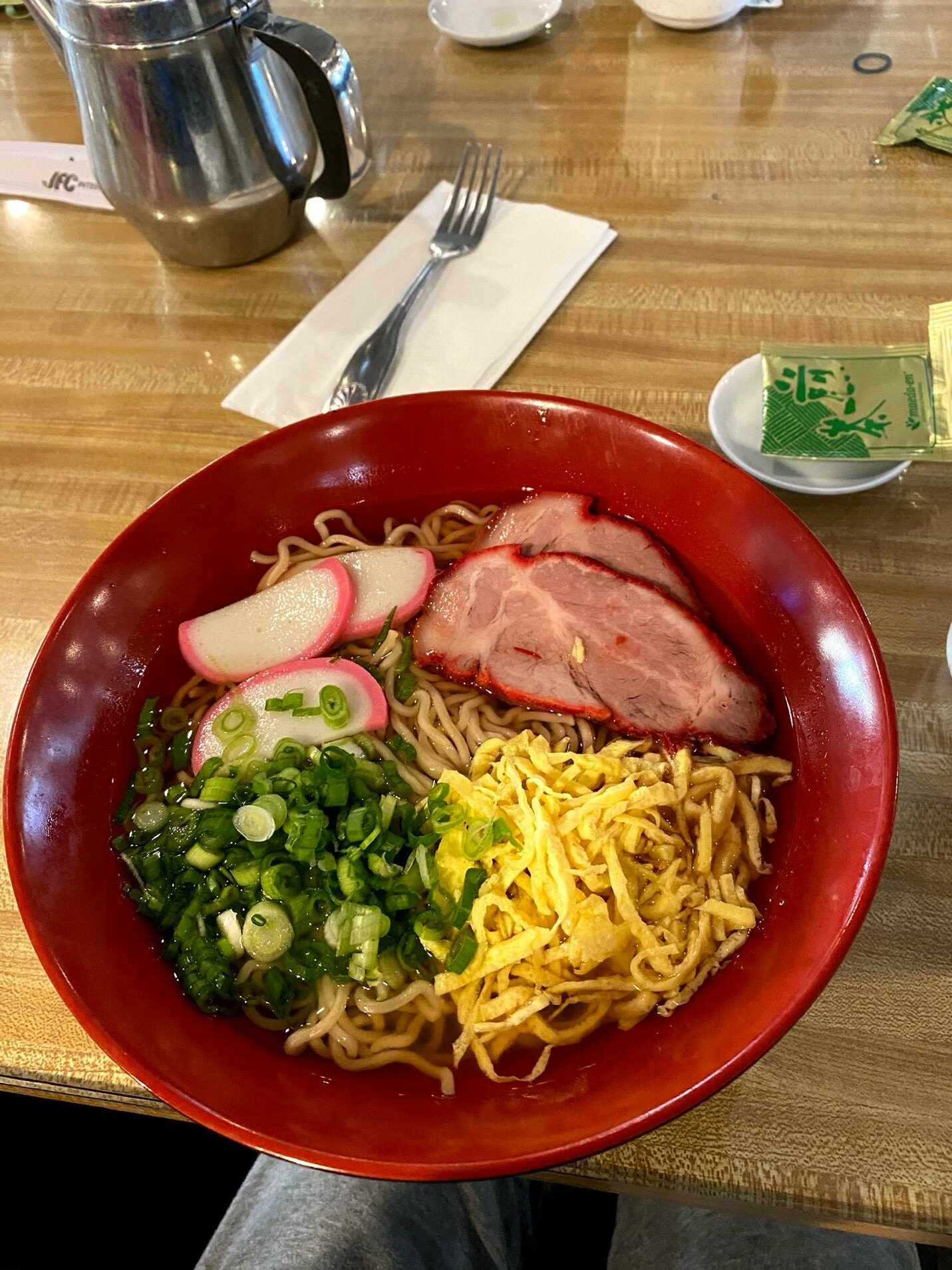

My father was a gambler, frequenting the local gas station after hours to play poker. When I began work at The Rafu Shimpo, I began to understand the full embrace of gambling in the larger Japanese American community. Many Japanese American retirement celebrations, veteran and World War II gatherings, and family reunions were held at the California Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. After a long night at the gaming tables or slot machines, you could order a hot bowl of saimin noodles—a Hawaiian standard—at its Asian restaurant. Saimin is similar to ramen but is usually served in a clear broth. Its egg noodles are distinctive, wavy and chewy, and usually topped with char siu, Cantonese-style roasted pork.

Gardena Bowl, much like the now shuttered Holiday Bowl in the Crenshaw District, is perhaps more famous for its food and communal gatherings than for its bowling. Edwin claims its coffee shop boasts the best bowl of saimin in Southern California. It’s simple, which is difficult to find these days, he writes. Gardena Bowl makes their own char siu and I think that makes a difference. The noodles are not overcooked and the broth not too salty, has good clarity (I don’t like foggy broth) and is very hot. Important on those cold nights. Presentation is clean. You see the pride in the care of their food.

But you have to eat the bowl right there, not to-go as it is offered during the pandemic. I look forward to the day when I can saunter into the coffee shop, bump into an old friend, and let the steam of a bowl of saimin moisten my eyelashes.

*

Along Western Avenue, on the central southern edge of the city, sits Gardena’s Japanese section. It’s not called that, but I can’t help but think of the blocks stretching from north of 162nd to 166th streets in such a way. Once upon a time, the area was home to Yo’s Custom Rods and Tackle Shop, where you could get a saltwater fishing pole wrapped to face a 100-pound bluefin tuna on a deep-sea expedition, or Saeko Oyama’s Let’s Knit Yarn Shop, where a bride- or groom-to-be could order a 1001 origami crane display. Those places are gone now, but other landmarks continue to buoy this legacy neighborhood.

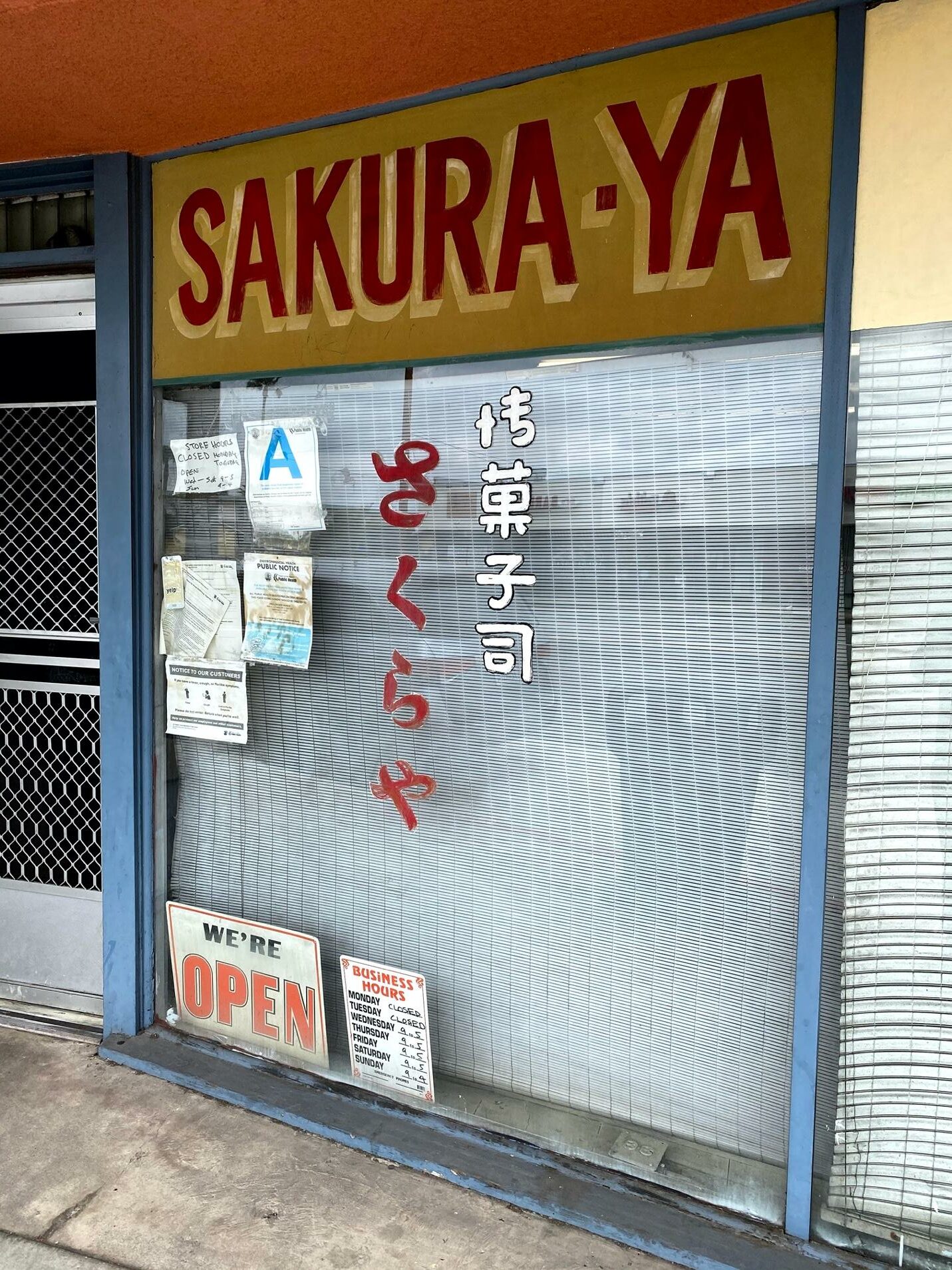

Whereas San Francisco’s Japantown is fighting to keep its one confectionery store open, the Gardena section has two—Sakura-ya and Chikara, only 256 feet apart. By confectionery, I mean a shop that sells mochi, the soft, sweet treats that often contain red bean (although I usually veer toward solid mochi), or manju, baked sweets.

You’d think there would be competition between the two family-owned businesses, because aren’t they selling the same product? Mochi/manju aficionados know better. Sakaru-ya boasts creations so soft that they practically dissolve in your mouth. Simple, unadorned disks, nothing unexpected.

Chikara, on the other hand, features confections as intricately decorated as a Fabergé egg. There are usually seasonal offerings. You buy a box of Chikara manju to impress friends at a party, bring cheer to a sick friend, or impress relatives of a romantic partner. Chikara signals that you are serious and committed.

I’m more of a Sakura-ya woman, I have to admit. Among my favorites are the orange mochi without filling and kinako mochi, a cylinder of soft green with smooth red bean inside and kinako, roasted soybean powder, sprinkled on top. As with the offerings from Sakae Sushi, these delicacies are in my mouth before I reach the car.

Edwin sometimes passes through this part of Western during his morning walks. During the depths of the pandemic, he observed four people, socially distanced and spaced appropriately in a line outside Chikara. A few steps later, two people were doing the same outside of Sakura-ya. We all needed a bite of comfort that could not be satisfied in any other way.

*

Further south on Western is a cluster of buildings that don’t match but belong to the same organization, the Okinawan Association of America (OAA). If you are not part of the clan, you’ve probably never entered the reflective multi-level central structure or the adjoining presentation spaces. It’s not that visitors and newcomers are unwelcome; it’s more that the buildings are hidden in plain sight. In one of my favorite Japanese folk stories, “Tongue-Cut Sparrow,” a wounded sparrow takes an older couple to Sparrow World, where life is animated and colorful, full of dancing. OAA is like that at certain times.

When I visited the OAA before the pandemic, there were traditional dancers, not in shibui, the muted colors of Kyoto, but in bright neon yellow and tomato red costumes. In another room, musicians strummed snakeskin-covered, banjo-like instruments called sanshin or shamisen, while students of all ethnicities practiced the endangered Okinawan language of Uchināguchi. Both sets of my husband’s grandparents were from Okinawa. His maternal grandmother, Kame, was more popularly known as Mama for her matriarchal hold over her blood family as well as the larger Okinawan American community.

In her fourplex in the Uptown area of Los Angeles, she might be discovered stirring a pot of boiled snake, a delicacy in Okinawa, or giving goya, bitter melon, to her Dominican tenants. (We are still wondering how these neighbors prepared the melon!) Gardena is one of the few spots where a restaurant such as Kotohira (in Tozai Plaza on the corner of Redondo Beach and Western) offers an Okinawan menu, including goya chanpuru, a type of stir-fry with the bitter melon, and two kinds of Okinawa noodles. As Okinawans reportedly live longer than any other humans, their food is worth checking out.

*

In Life After Manzanar, a book I co-wrote with my friend Heather Lindquist, we traced the threads that led from the World War II detention center in the Owens Valley to Gardena. The head Buddhist minister at Manzanar, Shinjo Nagatomi, came to Gardena with his wife and two young daughters after being released from the camp on the day before Thanksgiving, 1945. He and his family had waited until all the inmates left. The last ones remaining, including the Nagatomis, numbered forty-nine.

I had heard of Evergreen Hostel in Boyle Heights but was unaware that Gardena Buddhist Church supported its own hostel as well. Its sanctuary and Japanese language school housed people released from the ten detention centers. Since I had an address for the hostel location, I drove around the perimeter of the temple, attempting to find the exact spot. The closest current building was a yellow stucco duplex with a white garage where pots of succulents were sold. The proprietor, an Asian immigrant, showed me a paper with a grid of prices for different-sized containers. Although my questions about the resettlement of Japanese Americans in 1945 were not answered, I did take home a medium-sized pot of aeonium for three dollars.

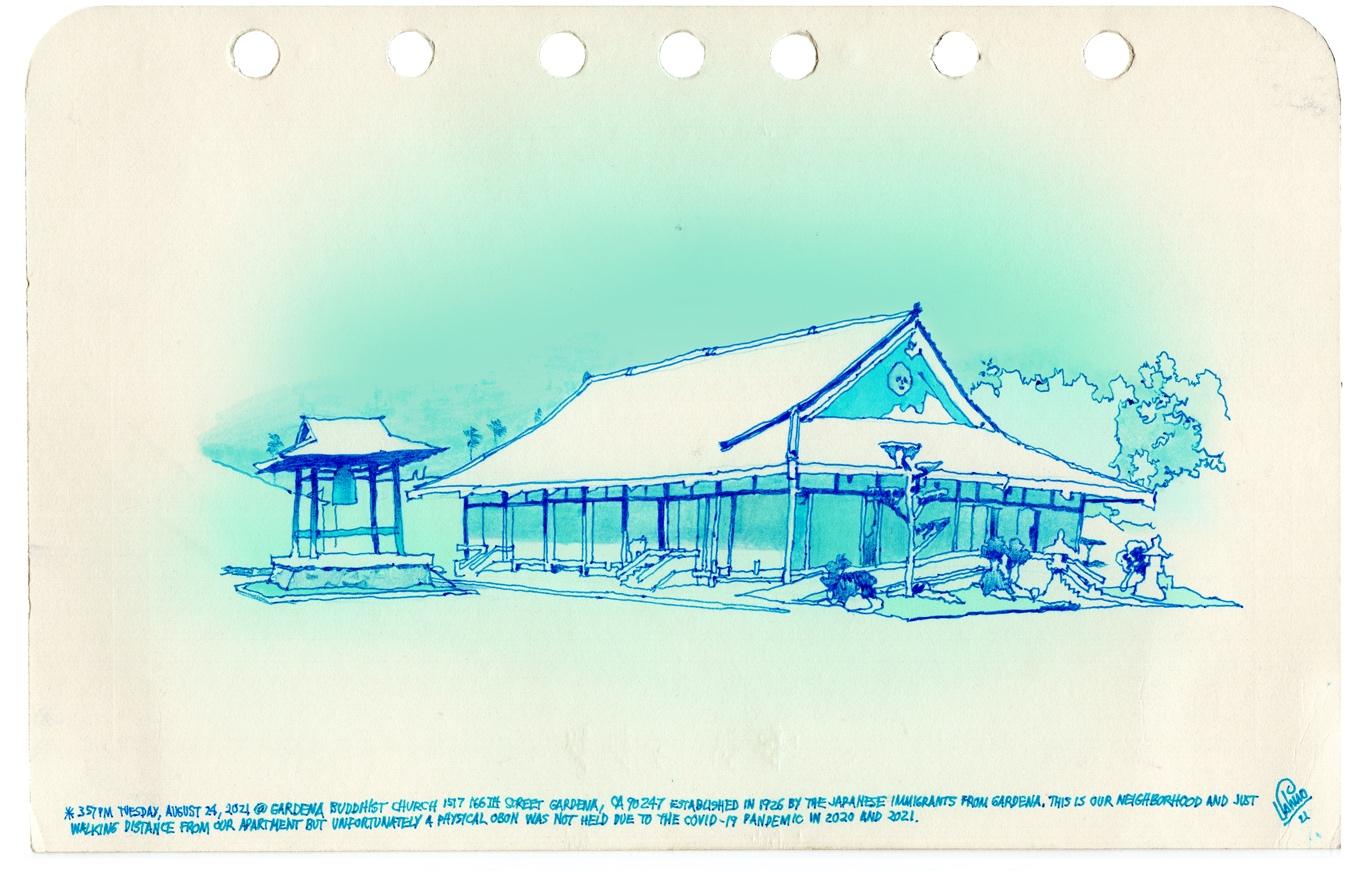

Gardena Buddhist Church, with its majestic sweeping black tile roof and bell tower, is a story of resilience. In July 1980, an arsonist burned the temple down to the ground. The members, many of whom had either been held in World War II mass incarceration camps or were descendants of people who had, raised funds to rebuild. Then in November 1981, the arsonist, still not apprehended, hit again. Unbelievably, the culprit struck a third time in February 1982. Luckily, this fire was discovered early and localized to a section of the sanctuary.

The perpetrator, a man named John Alden Stieber, confessed months later to Gardena police, who had been stumped in the case. In addition to the Gardena Buddhist Church, Stieber also set fire to two area Catholic churches, a Baptist church, and a Presbyterian church. The courts deemed him insane. He claimed that he was on a mission to stop a conspiracy by the Catholic Church, the Bank of America, and the Japanese people to take over the nation.

It cost more than a million dollars for the property to be completely restored. Now, the scars of this traumatic period have disappeared. Prior to the pandemic, community members in brightly colored happi coats and cotton yukata would gather every summer at the popular Obon Festival to dance, socialize, and eat goodies like Okinawa dango, similar to donut holes but much heavier and earthier.

I doubt younger members of the congregation are aware of the temple’s role in helping Japanese Americans make the transition back to the “free world” in the 1940s. That the temple was able to rise up multiple times testifies to the Japanese proverb, “nana korobi, ya oki.” Fall down seven times, get up eight. Today, as we attempt to recover from the pandemic, I hold onto that adage.

Maybe that’s why Gardena weighs powerfully in our collective Japanese American minds, or at least in mine and Edwin’s. We recognize the pain of removal and displacement while reclaiming the place, or at least a corner of it, as ours. So when I pull off the paper from that Sakae Sushi box or dip my hand in the bag stamped Sakura-ya, it’s not merely for the vinegary snap of marinated mackerel or stretchy pull of mochi. Contained in those culinary experiences are memories of what sustained our community, not only during my lifetime but even before I was born, when the strawberry fields dotted the valley. Each time I stop by Gardena, I’m breathing in snapshots of my very existence, the institutions and cultural practices that helped to form me, the care and preparation of food not for Michelin star status or Instagram but rather for walk-in customers with a balled-up ten-dollar bill in their pockets and a glint of anticipation in their eyes.