A breeze blew into the kitchen from the cooler in the living room as Grandma Nellie made scrambled eggs with nopalitos (chopped prickly pear cactus paddles), chopped yellow onion, and a sprinkle of salt for my younger sister Cynthia and me. During summer breaks from elementary school, Cynthia and I spent weekdays at our mother’s parents’ home in the San Bernardino Valley. Grandma Nellie would serve us the nopalitos for breakfast or lunch, with flour tortillas made by hand and warmed over the burner flame. Cynthia and I tore the tortillas into triangles that we used to scoop our food and eat. Such a simple dish, yet so delicious.

I savored the tart flavor and thick texture.

Later, when I was in my mid-twenties, Mama began to make cactus salad for family parties—inspired by a Japanese-Filipino American co-worker who brought one to a potluck at the San Bernardino County courthouse, where they worked. This is the first and only dish I remember Mama making with nopalitos.

Although nopalitos are a staple in many Mexican immigrant and Mexican American households, Grandma and Mama rarely served them, so I considered them special treats. Neither Grandma Nellie nor Mama had a nopal plant in their yards when I was growing up. They used jarred nopalitos from the local Stater Bros. market. Mama got the recipe for her cactus salad from the label on a jar. Over time, she substituted and added ingredients, finally settling on Anaheim chiles, green onions, garlic, tomatoes, oregano, cilantro, carrots, bell peppers, and black olives. Not long ago, stumped about what dish to bring to a Mardi Gras party, Mama created what she referred to as “Mardi Gras cactus salad” by adding purple cabbage and corn to match the traditional colors of the celebration.

Her salad was a hit.

I never ate fresh nopalitos until I was in my early thirties. They made nopalitos from a jar seem limp, rubbery, and vinegary. Naturally mucilaginous, fresh nopalitos have a mildly earthy scent and are meaty and tender-crisp, like blanched green beans. I promised myself that when I became a homeowner, I’d grow a nopal in my yard.

In early 2010, a few months after buying a home in North Long Beach, my spouse Jorge and I planted a nopal in our backyard. I learned to harvest and clean the cactus from YouTube videos, as well as articles on websites and a lot of experimentation on my own. Honing these skills and making dishes with nopalitos gives me joy and connects me with my mother and maternal grandparents, as well as my Mexican roots. Through trial and error, I mastered positioning my body to avoid the prickles—many as thin and translucent as baby hairs and tiny and sharp as metal slivers—that would get stuck in my clothes and hands when clipping the shiny green nopales. Some prickles have remained in my clothes through hard shakes and multiple washes, surprising me when they pierce my belly or my hips. This is a continual reminder to be cautious and move slowly when navigating the nopal.

I tried several strategies to remove the prickles from the nopales without getting them stuck in my hands. Some were so miniscule that a magnifying mirror was required to find them on my fingers and the curves of my palms. Gloves were out of the question because I find them cumbersome. One article I read suggested burning off the spines and prickles, but it made a mess in the sink and colored the skin of the nopales a sickly gray. Not only that, too many spines and prickles were left behind. In the end, patience and a paring knife worked best. I’m sure there’s an easier, quicker way, but taking the time to find and remove the tiniest prickles centers me.

Today, my nopal is taller than our neighbor’s one-story garage and as wide as our Meyer lemon tree. It looks like a giant otherworldly being, a descendent of nopals planted by goddesses during pre-Columbian times in Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Aztecs. Large, oblong jointed nopales extend from the base like outreached arms. Tunas—prickly pear fruit—the color of orange sherbet and just as sweet, grow from the edges of the large nopales like fingers, fanned out and reaching skyward toward the sun.

It seems I’m carrying on a tradition. Recently, Mama told me that during her childhood, Grandma Nellie grew a nopal in the furthest end of their backyard. Grandpa John harvested and prepared the nopales for cooking. Mama fondly remembers helping him remove the “picas”—the word our family uses for prickles—from his hands with tweezers. She only recalls two of Grandma’s nopalitos dishes: the same scrambled egg dish she prepared for Cynthia and me, and chile colorado, a Mexican pork or beef stew in red sauce.

Grandma Nellie grew up in a Mexican immigrant and first-generation Mexican American neighborhood on the Westside of San Bernardino. Mama and I speculate that she learned to make these dishes from her mother, Pilar. Great-Grandma Pilar died two years before Mama was born. Most likely, she grew a nopal in the backyard of Grandma Nellie’s childhood home, as many of her Mexican immigrant neighbors did.

If Great-Grandma Pilar didn’t teach her to make nopalitos dishes, Grandma Nellie may have learned from women in the neighborhood. Mama grew up two blocks from Grandma’s childhood home. She remembers Nina Chole—her godmother and her mother’s best friend—teaching Grandma Nellie to make tamales for the winter holidays. My grandmother’s first-generation Mexican American girlfriends also gave her tips on how to prepare other Mexican dishes.

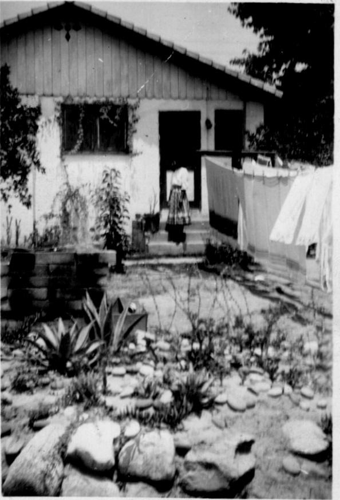

By the time I was born, the space where Grandma Nellie’s nopal had grown was paved over with asphalt to make a small parking lot for customers of the small grocery my grandparents ran in front of their home. Only a faded photograph of her cactus garden remains, the nopal outside the frame.

Grandma Nellie retired at fifty-two after having worked since she was twelve years old. My grandparents rented out their house and market and bought and moved into a second home two miles west on the border of San Bernardino and Rialto, in an area called the Rialto Bench.

Grandma Nellie didn’t plant a nopal or cactus garden at their new home. Perhaps because she now had a front yard to show off, she preferred to grow roses and other flowers. Perhaps Grandpa John no longer wanted to bother harvesting and cleaning nopales. Or perhaps Grandma Nellie felt that a nopal didn’t fit with her new neighborhood, which was mixed—Black, white, and Mexican American. Only two or three Mexican immigrants lived on their long street. None of the neighbors I knew grew a nopal.

Grandma Nellie died in December 2009. I wish I could show her my nopal and serve her nopalitos dishes I’ve created or learned from those served at restaurants and friends’ homes. Nopalitos stirred into frijoles de la olla, mixed in pico de gallo, tossed in a green salad, wrapped with avocado and kalamata olives inside a sprouted grain tortilla, or smothered with vegan mole oaxaqueño from Rocio’s Mexican Kitchen in Bell Gardens. The proprietor, Rocio Camacho, is known throughout Los Angeles County as La Diosa de Moles, the goddess of moles.

I’m not a good cook like Grandma Nellie, and certainly not like Rocio. I don’t enjoy making dishes that require more than two or three steps, so nopalitos are perfect for me. Although time consuming to prepare, they’re easy to cook—whether boiled in a pot with garlic or grilled in a cast iron pan. Not only that, nopalitos are good for you. The mucilage is anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, high in fiber. It decreases blood sugar and LDL cholesterol.

The tunas that decorate the edges of older nopales are nutritious, but much easier to clean. When they’re in season, I share them with friends and take bagfuls to Cynthia and my parents when I visit them in the Inland Empire. If the workers we occasionally hire to do repairs show interest, I tell them to take as many nopales and tunas as they like. And I can always count on the mockingbirds and fig beetles—their iridescent emerald green bodies and golden tan trim firme as a custom painted lowrider—to help eat the tunas. Yet many still get left behind to rot. Last year, I advertised free tunas on the neighborhood social media pages and was surprised at how many people responded. I met many neighbors for the first time.

I’ve failed at growing a basic produce garden with tomatoes, squash, and herbs. Meanwhile, my climate-friendly, giant nopal thrives. It flourishes in harsh heat with little to no care and generates nutritious, hydrating food for humans, animals, and insects.

Grandma Nellie would be proud.