The art of curation is, in a sense, the art of arranging physical objects in space. It’s a practice in which the materiality of art, in a word, matters. An exhibition creates resonances between works through physical proximity. Two recent concurrent shows at the Whitney Museum of American Art, “Julie Mehretu”–a mid-career retrospective of the artist–and “Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950-2019,” emphasize this aspect of curation and and opens up new interpretive possibilities of the art itself.

Mehretu’s Sun Ship (2018; ink and acrylic on canvas) and Lenore Tawney’s Spirit River (1966; linen and steel rods) are standout pieces from these respective shows, whose titles imply motion, transcendence, journeying. The pieces are roughly above and below one another, facing us as we face the Whitney’s walls abutting the Hudson River. This implied dialogue brings out a subtle but significant thread in both shows, namely how a sustained contemplation of physical material yields unexpected routes for reimagining spirituality across visual culture.

Born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in 1970, Mehretu has charted a career as one of the most significant visual artists of the new millennium through a distinctive approach to imaging the African diaspora. Her aesthetic tends toward a monumental abstraction that blends the iconographic with the cartographic. Stasis and flux are the retrospective’s uniting principles. Earlier pieces such as Renegade Delirium (2002) and Stadia II (2004) are in the style most museumgoers will recognize if even cursorily familiar with her work. They have the appearance of an Olympics worth of flags digitally flattened into a camouflage of geometric abstraction. Mehretu’s paintings incorporate ancient visual sources like stelae and hieroglyphics, while swirling shapes complement curvilinear lines to form vortex spaces at their centers. Staring at her monolithic canvases is a look into the hurricane’s eye, with emblematic data flurrying past. These are paintings as meteorological weather patterns, where unruly and noodling geometries race across a defined surface layer. Babel Unleashed (2001) blends the cartographic with the cataclysmic, an exemplary showcase of Mehretu’s inquiries into urbanism and political upheavals as if viewed by a planetary consciousness.

Indeed, the more recent Sun Ship (J.C.) (2018) finds Mehretu shifting to a more cosmological ethos. In a recent interview in Rain she reflects that

we invent new names for new songs, new forms of music, or new ways of thinking or new ways of being in the world, so that’s kind of how I play with the marks. They’re being stretched and formed and pulled to mimic certain parts of early Renaissance paintings in terms of space, but also prehistoric moments in terms of marks, protruding into extreme forms of Afrofuturist possibilities.

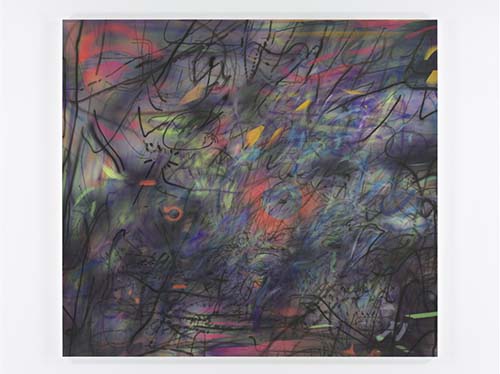

At Sun Ship’s center is what looks like a lunar eclipse near a planet-sized orb. The painting’s edges are choked in black smoke, while a purple fog drifts above a discordance of neon bands and calligraphic squiggles. The orbital marks of Sun Ship hover, luminously, within a scatter of lines and circles. Mehretu’s symbolic wellspring, from diasporic history to our scattered digital present, turns Sun Ship into a space odyssey through a collective visual unconscious. Marking is a form of mapping in Mehretu’s practice, a way to envision spiritual journeys of a wildly new kind.

In a previous generation, Lenore Tawney (1907-2007) was among a cadre of artists including Ellsworth Kelly and Agnes Martin whose formative years in Lower Manhattan’s Coenties Slip became a source of postwar minimalist lore. Her role in the development of fiber art established her as a central figure of craft art and has inspired renewed attention by contemporary art historians, signaled by the prominent display of several of her works in “Making Knowing.” In the show’s press release, the curators argue that “craft-informed techniques of making carry their own kind of knowledge, one that is crucial to a more complete understanding of the history and potential of art.” Craft art utilizes materials that have traditionally been dismissed in high art circles as a reclamation and reconfiguring of domestic and decorative materiality. The exhibition reveals that there are many ways to know, and many conduits to wonderment through the tactility of often unassuming materials.

“Making Knowing” boasts names such as Agnes Martin, Yayoi Kusama, and Robert Rauschenberg, but one of its great virtues is the sense of rediscovering spiritual, even supernatural, experience through craft materials. There is Kiki Smith’s Familiars (2001-02; a wool blanket made in collaboration with The Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia), which uses a pattern of constellated stars crowning a woman surrounded by animals and the English nursery rhyme lines “I see the moon and the moon sees me” to fashion an arresting iconography of witchcraft. Two thousand miniature porcelain teacups, goblets, and shakers comprise Charles LeDray’s six-level glass cabinet Milk and Honey (1994-96), a culinary meditation upon the infinite that suggests food’s mystical hold over our senses. “Making Knowing” celebrates art that endows familiar material with a magical sheen of possibility.

Tawney’s Spirit River and Mehretu’s Sun Ship are skeleton keys to an undercurrent that tethers both shows into a conversation about the power of physical material to mediate radical encounters with presence and transcendence. The title of Mehretu’s Sun Ship (J.C.) references the John Coltrane record of the same name from his late-period output of cosmically ambitious jazz spirituals. There is music within Mehretu’s canvas, a synesthetic encounter with ink and acrylic chords and scales akin to the diffuse yet detectable melodies embedded in Coltrane’s frenzied solos. Materiality generates a paradox of its own in Spirit River, where black and subtly evocative purple linen produces a hallucinatory glow, mimicking the liquidity of flowing water.

Meanwhile, Tawney’s Spirit River was completed in 1966. It is fitting that at the same time Tawney was weaving this piece in her Manhattan studio, John Coltrane was recording the saxophone solos for “Ascent” and “Attaining” in a nearby studio. The yogic practice that ultimately became central to Tawney’s spirituality is visceral in this piece, its linen and steel rods like woven sutras, tributaries of stillness flowing down this black and purple river suspended in midair, a weaving of water that is rightly transubstantial. The directionality of Spirit River, with thin strings becoming thick bands, has a questing, meditative quality reminiscent of Coltrane’s sonic prayers.

Like the utopic spirituality given form in a track like “Ascent,” Mehretu’s marks on the canvas of Sun Ship and Tawney’s weaving of a river become vessels for charting the physical manifestation of a spiritual journey.