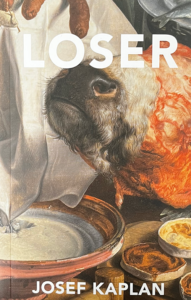

Loser

by Josef Kaplan

Make Now Books, 2021

150 pp, $20.00

Rhetoric gets a bad rap. Employed most often to dismiss an opponent’s position out of hand, the word first appears in a dialogue of Plato’s as an epithet to diminish the teaching of his interlocutor, the sophist Gorgias. Rhetoric has the look and feel of truth without being the truth. It plays on our worst tendencies, we say, candy coating otherwise impolite opinions and excusing our baser instincts.

The positive correlate to mere rhetoric is, of course, sincerity, a mode of speech that provides an immediate and unambiguous manifestation of one’s true self. But as we all know, displays of sincerity can easily be captured and used for rhetorical purposes. Hence virtually all of politics, marketing, PR, and social media. It seems, then, that in the antagonism between rhetoric and sincerity, rhetoric always has the upper hand.

It is precisely at this point of contact, where sincerity is meant to solve the messy relationship between poetry and politics, that Josef Kaplan’s newest book, Loser (Make Now Books), deploys a highly rhetorical style to hold open the space between speech and belief, highlighting the critical importance of this mutual independence not only for poetry but, ironically, for politics as well. Readers familiar with Kaplan’s previous books—Poem Without Suffering, Democracy Is Not for the People — will find in Loser a continuation of the stylistic preoccupations evident in those books, namely a highly ironized, performative orality channeled into a rambling monologue, full of artfully deployed clichés and phatic expressions.

Loser comprises two long poems, “Crying” and “Begging,” the first in verse and the second in prose and both taking the form of a monologue by an unidentified speaker. The monologues take place in the aftermath of an unspecified but clearly violent social event. In the first poem, the speaker is on the losing side; in the second, they are on the winning. “It was a catastrophe. / Plain and simple,” the speaker says about their loss in “Crying,”

An utter

disaster.

There’s nothing

redemptive about it,

no speck of comfort

to glean,

no lessons

to appreciate,

nor ghostly

whiff of optimism

Similar descriptions of defeat and expressions of fear of reprisal gradually shift toward regret and self-loathing, particularly regarding the speaker’s former position within a sub-sub-culture of political (or perhaps, aesthetic) gadflies. Far from a popular movement, the speaker forms part of a self-styled vanguard whose entire essence is devoted to rationalizing its irrelevance and whose obscurity is a function of its resentment:

To say we were

“minor” is

too generous,

To say we were

“obscure” is too

romantic.

. . . . . . . . . .

we seemed hermetic,

contradictory —

an obstacle,

obnoxious

at the very least,

and at most,

a relatively

determined

hindrance.

Readers of Roberto Bolaño’s work, particularly The Savage Detectives, will recognize that such language can describe both a political cell or an avant-garde literary group. And as the poem progresses and the violence reaches a crescendo, this sentiment of defeat becomes uncannily familiar, a familiar part of a contemporary world that consists of a long string of defeats and disappointments.

Even more than “Crying,” “Begging” is ambiguous as to its context and digressive in its content. With the generosity of a righteous victor, the poem’s speaker implores, in Psalmaic cadences, that their “enemies” be either punished or granted various powers and insights:

Let them bear no fruit.

Let their talents, dazzling and unprecedented, elicit only pity.

Let every courageous deed immediately wane, let their certainties meet only indifference.

. . . . . . . . . .

Give them a buoyant, righteous heart.

Give them humor.

Give them a cool head and firmness in conversation.

Give them a beautiful physical life—attractiveness, fitness.

The tone is by turns kind and cruel, and the language can become so oddly mannered that it’s difficult to gauge the sincerity (or the insincerity, for that matter) of the voice. Employing the rhetorical figure exergasia, repetition of the same idea using different words, the speaker imagines,

My enemies and myself, laughing together, as one — our laughter combining into rising intervals of more and more complex, interwoven patterns, the harmonics of our individual voices laced through each other, gaining in volume, gaining in strength and depth, delighting each other, climbing into more greatly compounded registers of intonation, lengthening and increasing, spiraling nearer still towards a spectacular richness of contrast that, at first notice, seems outside the possibilities of a throat’s articulation. . .

Are Kaplan’s speakers talking about aesthetics or politics? Is there a difference and, if not, at what cost? It’s a question that has occupied critics at least since Walter Benjamin, and this sometimes-turbulent, always-fuzzy boundary between aesthetics and politics grounds the central ambiguity of the book. The ambiguity is not for ambiguity’s sake, but is central to the reading experience as a performance of inadvertent complicity, of not being able to buy or talk or perform one’s way out of history’s abattoir, and it is a testament to the charm of Kaplan’s style and the sometimes silly, sometimes sardonic humor peppered throughout that one is continually attracted and repulsed, empathetic and scornful, even having long put the book down.

In “Begging,” while the speaker is trying to win over their interlocutor, the conflation between art and politics is made explicit. In denigrating the work of their victorious opponents, the speaker complains in confiding tones that

There’s nothing being said about politics or art. There’s no real political stakes. They’re not proposing some kind of new aesthetic model… They’re not proposing anything, actually. Anyone who’s smart or paying attention will see that. It’s all just posturing and personal beef. It’s like a feedback loop of personal, ad hominem shit, elevated (they think) to the level of structural critique. I’m telling you, dude, you’ve just got to ignore it. You can’t do anything against that kind of performative bullshit. These people aren’t looking for any actual engagement, they don’t want to, like, be discursive, or challenged about any of this. They just want their narcissisms satisfied. They just want to be cheered.

The argument is not unconvincing, and that is precisely why the book continues to haunt the reader after reading it. After all, who doesn’t want to hear that their genius has—unfairly!—gone unacknowledged, and who among us (hypocrite lecteur) doesn’t know a writer or two who talks a good game but is really just vying for a cut of Lilly’s millions or a commission from this or that cosmetics line or fashion house.

The poems trade in the anxiety provoked by a generalized uncertainty regarding where the speakers stand in relation to one another and to us as readers. Kaplan’s work implicitly distrusts any simple unity between poetry and politics that would deny their antagonism. Kaplan’s book never resolves the tension between the vague allusions to political violence and the rococo locutions that constitutes the pleasure of the text. That is to say, he never decides between the two, neither grounding aesthetics in a political position nor dissolving politics in rhetoric’s ambivalence. Where politics depends on solidarity and unity of message, poetry continually insists on magnifying minor differences in phrasing and word choice.

Poetry may be in some ways anathema to politics in the sense of a rallying dogmatism (Plato certainly thought so), but that doesn’t mean that it is not concerned with how we might reconcile conflicting interests. Language, the very stuff of poetry, resists its recovery and its recuperation—but it is precisely this resistance which grants an odd sort of access to language as resistance. That is to say, language is grasped only insofar as it escapes as if behind a smokescreen. When Gorgias argued against Socrates in favor of Athenian tragedy, his reasoning went, “he who deceives is more honest than he who does not deceive, and he who is deceived is wiser than he who is not deceived.” But only in our desire not to be deceived are we truly deceived. The one who “gets it” is duped beyond recovery, worse off by far than those who continue to puzzle over it, and in poetry, the ah-ha! moment is often little more than the arbitrary repudiation of ambiguity and uncertainty (the intolerance of which is linked to authoritarian personality types).

Loser reminds us the true extent to which poetry is dangerous, and in their rhetorical excesses, in professing too much, these poems reacquaint us with a deep truth of language, one hidden of necessity, which is that sincerity most likely developed originally as a ruse and that language is as much a means of deception and manipulation as it is one of consensus building and speaking one’s truth—if not moreso.

Poetry, finally, turns all sincerity into a confidence game. The only difference between poetry and deception is that poetry seeks to gain nothing—except, perhaps, to make you a little wiser. If Kaplan seems a bit of a knave, it’s only because he is truly a poet, an honest deceiver, and thus the thrill of Kaplan’s style: an absence of sentimentality that is not simultaneously the aggrandizement of a vulgar realism or, perhaps, (if I may be cute) a Realpoetik.

It seems obvious to me, at least, that a lack of a sense of humor (and of irony) makes for worse poetry than a lack of unambiguous partisanship. If the road to hell is paved with good intentions, then one ought to wonder what lies under these high-toned pavés? “Give them humor,” says the voice in “Begging,”

Let this laughter be relief, softly arriving.

For my enemies, let it be the loveliest moment.

Let it be for them an opening into respite, a trust they can reach into and take hold of.