A couple of years ago, I saw Elizabeth Povinelli speak at the West Hollywood Library about her forthcoming book, Between Gaia and Ground. As is typical of her work, her talk wound through an impressive breadth of topics, including climate change, decolonial movements, and questions of sovereignty. Povinelli has the capacity to work within and beyond the terms of academia, making complex, heavy topics seem urgent and accessible. She also screened a pair of films made by the Karrabing Film Collective, of which she is a member along with over 50 of her Indigenous colleagues. The collective is based in Belyuen, Australia, where Povinelli has worked as an anthropologist, activist, and collaborative artist since 1984. Povinelli’s works in different mediums echo and intensify one another while remaining singularly of their genre.

A couple of years ago, I saw Elizabeth Povinelli speak at the West Hollywood Library about her forthcoming book, Between Gaia and Ground. As is typical of her work, her talk wound through an impressive breadth of topics, including climate change, decolonial movements, and questions of sovereignty. Povinelli has the capacity to work within and beyond the terms of academia, making complex, heavy topics seem urgent and accessible. She also screened a pair of films made by the Karrabing Film Collective, of which she is a member along with over 50 of her Indigenous colleagues. The collective is based in Belyuen, Australia, where Povinelli has worked as an anthropologist, activist, and collaborative artist since 1984. Povinelli’s works in different mediums echo and intensify one another while remaining singularly of their genre.

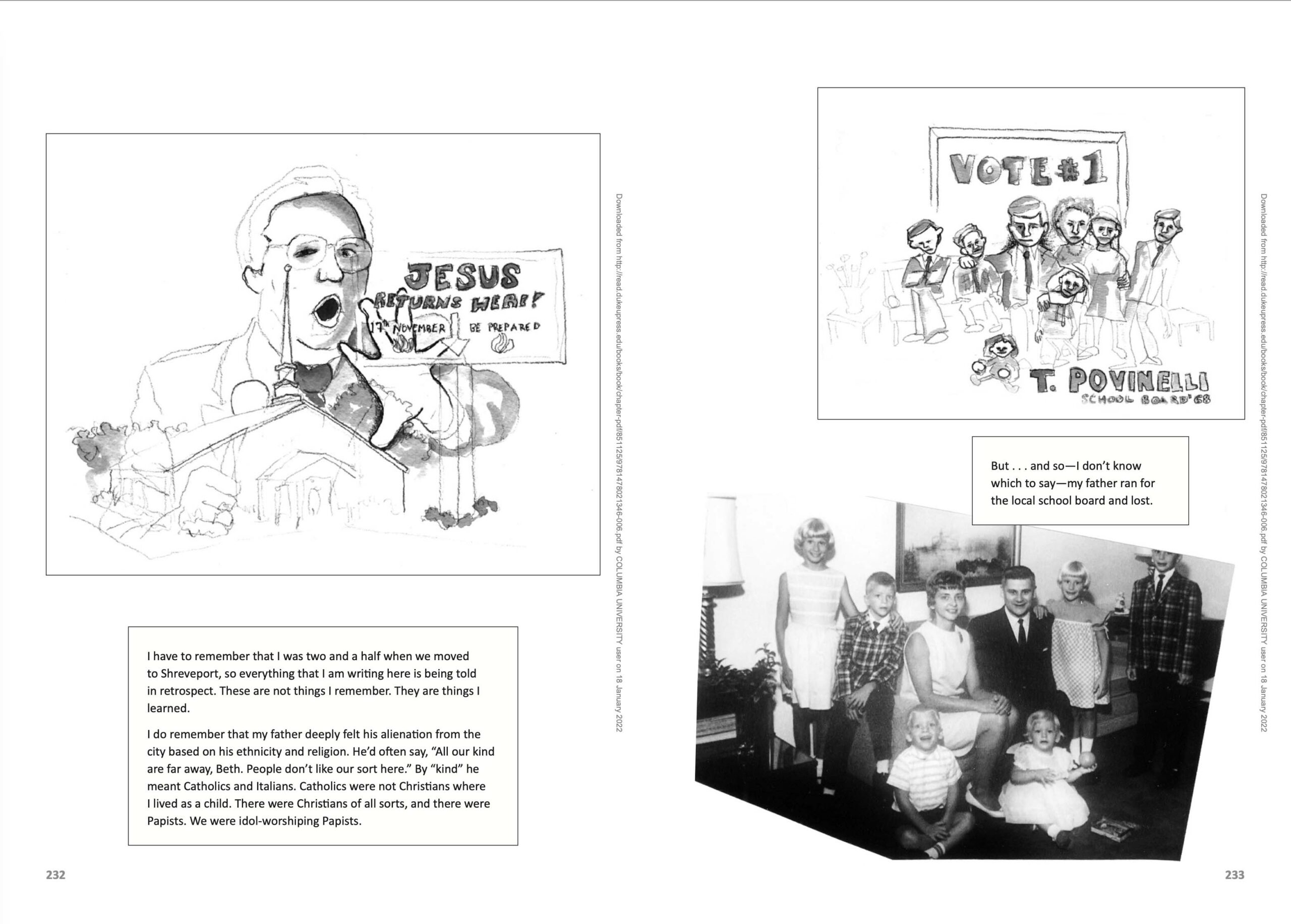

Povinelli’s latest cross-genre experiment is the graphic memoir The Inheritance (Duke University Press 2021). The Inheritance seamlessly blends the creative and the critical as Povinelli tells the story of her upbringing in 1960s Louisiana and a crisis that unfolded in her family around questions of lineage and identity. The result is a theoretically, narratively, and visually sophisticated take on the important question of inheritance, of how we imagine the stakes of the present in terms of the (often contested) past.

I spoke with Povinelli over video chat recently. She called in from New York City, where she is the Franz Boas Professor of Anthropology at Columbia University. In our wide-ranging conversation, we talked about art-making and scholarship, as well as the conceptual and stylistic underpinnings of The Inheritance.

Many of your previous books include drawing, paintings, and hand-written notes. What role did drawing play in your scholarship and thinking prior to The Inheritance?

My drawings have been of two sorts in my research-driven writing. On the one hand, I have used them as covers for some of my books. For example, the cover of The Empire of Love is a painting of mine. This same painting shows up in The Inheritance. I included this image in The Inheritance because it situates me and my five siblings within Lacan’s diagram of the mirror stage. The cover of Geontologies is a collage of gesso, pen drawings, and dictionary extractions. The image has a built-up surface that you can just make out on the cover if you know what you’re looking for.

Another sort of drawing has populated all my books, that is, diagrammatic thinking—I often supplement moments of my arguments with diagrams not merely as illustration but as a different way of conveying thought. And I always think, “Oh, this will really help people see what I’m saying.” But then someone once told me: “You know, Beth, I think I’m understanding you, and then I get to your diagrams and I think, Oh my god, I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

So, drawing is a mode of thought for me, one of the dominant modes in which thought appears to me. And this mode of thought has always littered my academic work. But there’s a pile of this kind of litter, including little videos, drawings, and sculptural works, in my nonacademic life. Sometimes pieces of it blow out of the pile and float around in the academic public sphere. Most doesn’t. Still, all this debris is crucial to how I create a surround that allows me to feel-build concepts.

The “otherwise” is a key concept in your work: a recognition that other worlds are possible and that other modes of being and knowing persist within settler late liberalism. You’ve also said you are pursuing an “anthropology of the otherwise.” Could you talk a bit about this aim and how your experiments with genre—both your artwork and your collaborations with the Karrabing Film Collective—might support it?

One way of answering this question is to recount an event that happened at the Melbourne International Film Festival. About eight Karrabing were present at premiere of When the Dogs Talked and Windjarrameru, The Stealing C*nt$. After the screening, we shuffled down to the proscenium for a Q&A with the audience. Now, picture us as a group—seven Indigenous people and me on the stage. An audience member raised their hand and directed this question to me: “It’s so interesting that you’re now doing ethnographic film. How do you think it affects your theoretical work?” The question made clear the issues of public visibility and Indigenous voice, if it wasn’t clear beforehand. I said something like, “Thank you for the question, but these are not ethnographic films, and they are definitely not my films.”

I think I said some stuff about us as a collective and that we don’t think of the director as auteur, but there kept being a repetition of the “Yes, but…” And I thought, What am I doing? So I said, “You know, maybe I should just let someone else onstage answer the question.”

Linda Yarrowin, an Emmiyengal Karrabing member, took the mike and said, “You know, we know Beth is an anthropologist because we know our parents made her be that. But like Beth said, Karrabing got nothing to do with anthropology.” Someone asked, “If it isn’t ethnographic film, then what kind of film is it?” And she said, “It’s Karrabing film.” I thought, “That is such a brilliant way of answering.” And, after having made eight-plus films together one can really see that there is a Karrabing genre. And I think that Linda’s answer gets to what I should mean by an “anthropology of the otherwise,” namely, to keep open and put effort into spaces that diverge from the governance of the self and other—it’s neither anthropological ethnography nor should it be defined by genres external to Karrabing social worlds.

So, Karrabing and I have thought a lot about the governance of genres; and I have thought a lot about how academics sometimes seem to feel most comfortable folding all aspects of their lives within the governing logic of discipline as genre. “As an anthropologist, I…” or “As an English professor, I…” “As an academic, I…” So sure, The Inheritance is a graphic memoir—or, a graphic essay in the guise of a memoir. But I would hope it has a much more awkward body than these summaries. That it has a genre-waywardness. Then maybe it can contribute to concept work, because concepts come from spaces that don’t fit into the current topology of power. This said, artwork is the place in which I can let other modes of thought run wild.

How did The Inheritance develop as a project? What were some challenges along the way?

The story of little Elizabeth has been with me a very long time. So has the broader story the book tells. And I have been drawing little Elizabeth with her funny little bowtie for years and years.

The Inheritance as a focused project began during that weird moment when DNA capitalism exploded. I started noticing the proliferation of commercials in which white people would say, “I thought I was Scottish,” and they’d have a kilt on, “but now I realized I’m Austrian,” and they’d now be wearing lederhosen. And I was, “What is this about?” Obviously, it’s about making money—capitalization of genetic technology. But what’s the anxiety behind it? This question intensified with the rise of White Nationalisms in the U.S. and Europe. I began to think about what I am now calling a post–late liberal “white counter-reformation.” Like the Catholic Counter-Reformation we’re seeing an attempt to retrench a form of global domination that simply doesn’t work anymore—we can say that white DNA capitalism and White Nationalism are symptoms of the effectiveness of the critique of white supremacism and settler colonialism. Whites are trying to find an Indigenous difference by digging into a precapitalist, precolonial, often pre-Christian past.

I started thinking about that, and I was like, “Girl, if anyone can do this kind of Euro-Indigeneity, I can—I’m a Simonaz-Povinelli; we were clan-based families who participated in subnational, village-based common governance stretching back at least to 1480.” But I wanted to use this as a history to show the false homology between Indigenous as a mode of settler dispossession and these older European forms of relationality as part of the infrastructures of this dispossession.

I initially tried to tell the story with almost no words, just images. I shared this version to see how much people could follow, and what affects it produced. Readers understood much of the story but then something didn’t work—like they couldn’t really separate out the parents and the grandparents. So, I slowly built out the writing section trying to give enough narrative sense without losing the visual disorientation. The drawings took years to complete.

Did you have any comics or memoirs in mind while you were making The Inheritance?

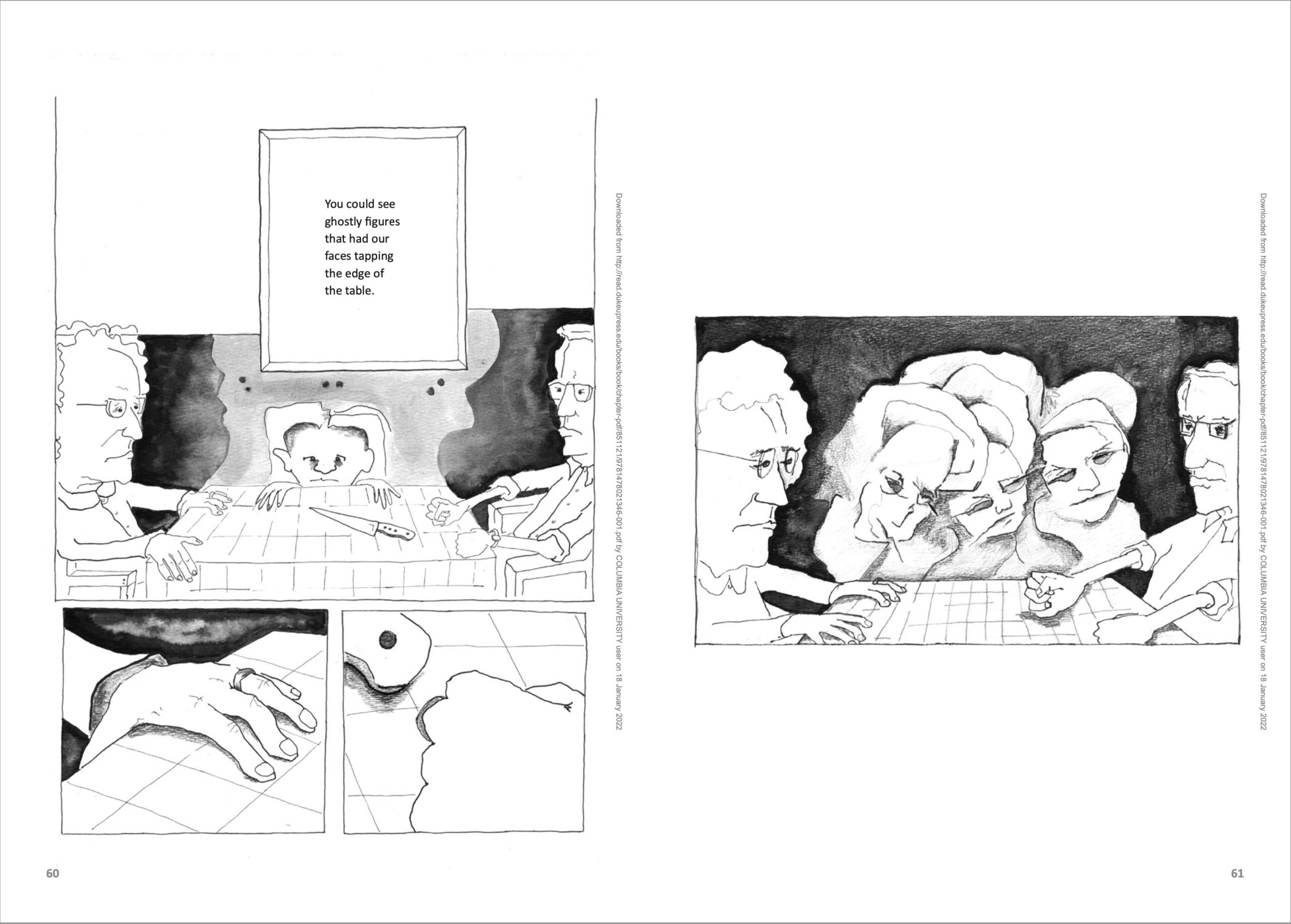

One of my touchstones was the works of Lynd Ward, one of the first graphic non-fiction writers. His books were based on wood carvings; no written text, so you just follow it like a silent film. I loved the way the textual silence produced such loud inner soundtracks. I intentionally avoided a comic-strip style. I wanted beautiful, stand-alone images—as many pages as possible to be something you could put a frame around and stick it on the wall, like the main character of the book itself: the framed image of Trentino/Tyrol [Ed. A region straddling the border of Italy and Austria]. Comic strips were too syntactic—too much like narrative film.

Another touchstone for all my work is the old Looney Tunes. They have tons of wild sounds, that great elongated animation work, but no linguistic sense. There’s one Looney Tune that scarred my life: Pigs Is Pigs. A little pig keeps eating his mother’s pies warming on a windowsill. One day this pig gets trapped in the cellar, and some sadistic scientist says, “You want a pie?” “Yes,” says the pig. In goes the pie. Repeat until the pig starts begging not to be given any more. But now pies are shoved into its mouth until he explodes. The horror of Looney Tunes—there’s an edge of that in The Inheritance, I hope. “Everything’s not OK here. The children are not alright.”

There’s a broad range of additional imagery in the book, from the contested map of Karezol/Carisolo [Ed. A municipality in Trentino/Tyrol in Northern Italy] to blueprints and diagrams to family photos and film stills. How did this archival interest complement or complicate the graphic memoir focus?

There’s a warning at the beginning: This book is not historically correct and the author is biased. I have five siblings, tons of aunts, uncles, and cousins, all of whom would tell this story differently. It’s not a history of truth in the archival sense. It’s a history of distorted memories and affects. I don’t even know which part is real or not. And, because I wanted to draw these distortions of affect and memory, I didn’t want to master the existing archive. I didn’t want to know exactly what went on according to recorded, recordable history because, if I found out, that would distort the distortion I was trying to draw. I had a very fraught relation to how much I was going to submit to archival reason and how much I was not.

I felt some freedom around this because by the time I was finishing The Inheritance I was engaged with what Karrabing and I call “the two-clan project”—tracking how Karrabing clans and the Simonaz clan are absorbed into capitalism and colonialism from the 15th century onward. So, I knew I was going to do a deep dive into the conventional sedimentations of history.

Hearing you talk about the affective distortions of the past, I think there’s a Looney Tunes connection there, too—it’s this kind of warping and pulling apart.

I think that’s really important. We also know the limits of a Looney Tune approach to history in a post-fact society. That’s why I put a flag post at the beginning of The Inheritance. If we are doing a Looney Tune history, why are we doing it? For me it was to show how not knowing, being in a scene of radical dispute, creates affective disturbances intensified when these disputes are occurring in the wake of dispossession. How do we show, draw, or narrate the affective reasoning behind the cathexis to one or another kind of story? Early animation seems so spot on—very funny, slapstick, tragic, and horrifying.

The Inheritance is also largely a critical reflection on whiteness—how it is produced and reproduced, how it relates to questions of origin, nation, and, of course, inheritance. I thought the book was particularly successful at complicating the relationship between ethnicity and whiteness, at interrogating the familiar idea that Italian-Americans, for instance, “weren’t always white.” Could you talk a bit about this tension and how it informed your aims for this story? What do you see as the larger stakes of this whiteness-ethnicity debate, particularly in relation to structural anti-Black racism, or what Hortense Spillers calls (and you cite as) “the American grammar of race”?

Well, first, we were not Italian. We didn’t speak Italian, we spoke Ladin. So, the first thing to note is really weird: We were not even Italian but were addressed as Italian. With “Povinelli” what else am I supposed to say I am? But, according to my Papa and still my father, we are Tyrolian. And Tyrol was part of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. They would say Karezol, the German pronunciation of Carisolo. So rather than nationally identified, we were village cathected. Carisolo was governed by the vicini (the local families) until the Napoleon wars—so very late actually. And it was important to Papa that we were not Italian. My grandmother, my father’s mother, on the other hand, was identified more with Italy. She lived in the village until the late twenties, so after the Italians absorbed Trentino. So identity and identification is split and splintered.

That said, when my great-grandfather and grandfather began moving between Buffalo and Carisolo, they were not the kind of immigrants that the Protestant elite wanted. We were semi-autonomous peasants. They were “uneducated” knife grinders. My family felt that. And when we moved down South my father felt unwanted because they saw him as a Catholic “dago.” That said, we were white, European. And no matter that for a long time Italians were “not white,” they were not Black and they were not Indigenous. In the U.S. this has always mattered. You could be spit on for being not quite white. But whatever you were, you were on the other side of the settler and racial line.

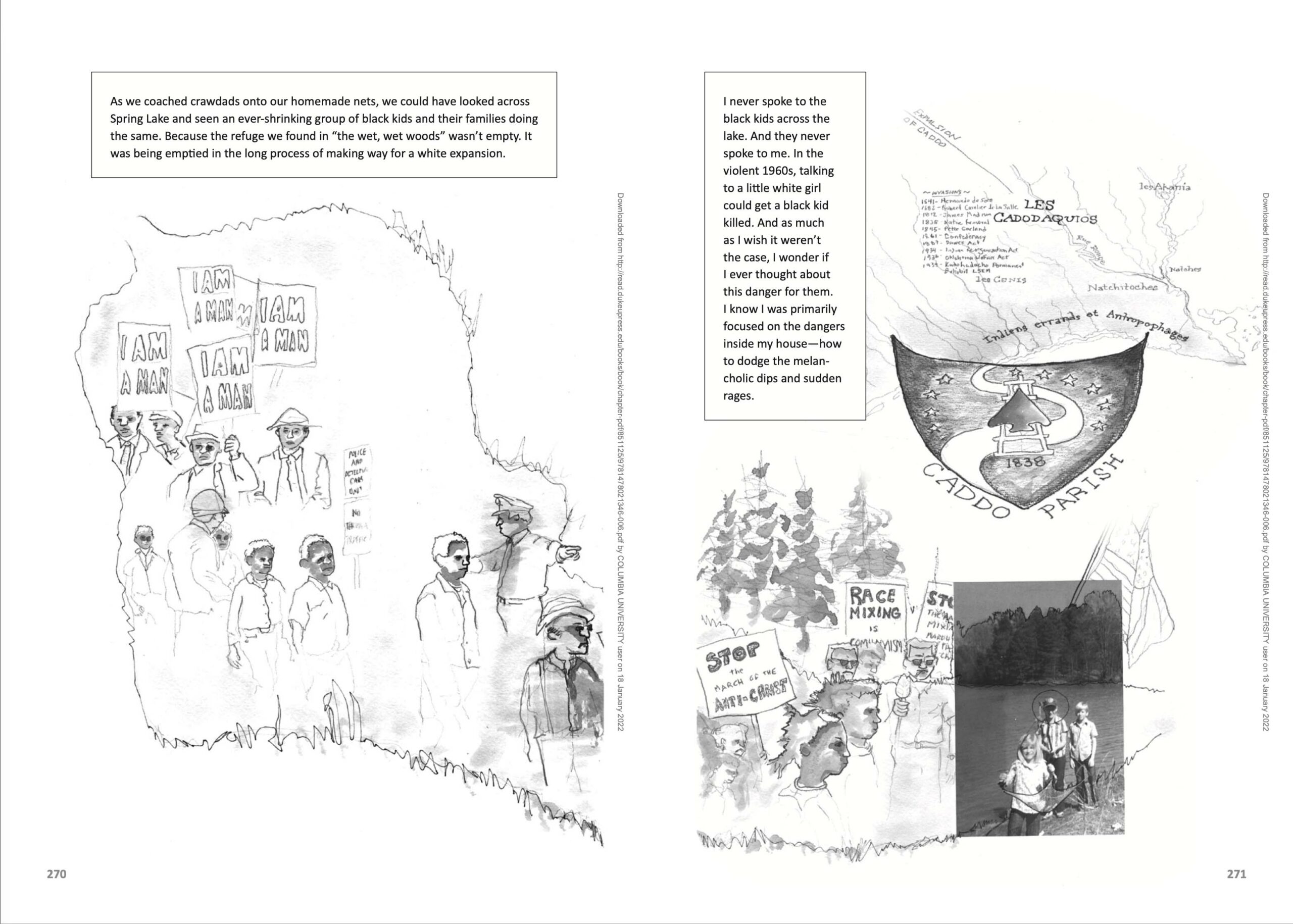

Of course, slowly ethnic whites are absorbed fully into whiteness. We know the history of the Republicans’ Southern strategy. Even by the time we moved to Shreveport, Louisiana, in 1964, our house was located within an area being developed as a white suburb. So while in our family drama, the drama is whether we’re Tyrolian or Italian, and about how Southerners don’t like Italians, from an infrastructural perspective we’re white. I try to get the internal drama on the page, but I also turn the narrative in Act III into this external, infrastructural drama—which frames us as just little white kids with a funny surname.

The Inheritance tries to show that we are actively inheriting the ancestral present rather than the ancestral past. We are inheriting the ongoing placement, or ongoing topology, of how bodies are absorbed in the infrastructures of power. My grandparents were within Carisolo and within the U.S. We got out of a European warzone because of an already existing path of dispossessed Seneca. What does history look like if you focus on these absorptions? I think this is what the white nativist counter-reformation is trying to get around—the sedimentations of values in bodies and lands. By pretending you can do an end-run around this history by saying, “We were also once Indigenous to places.”

Along that line, the idea of “the inheritance” is closely linked to issues of “accountability” and “privilege,” which of course are at the center of the national conversation but often elude concrete meanings. How can storytelling help to bring these crucial but complex issues into clearer view?

Yes, the question of accountability and privilege was always in the foreground as I drew and wrote. I thought of The Inheritance as a prehistory of my 38-year relationship with my Indigenous colleagues/family in Karrabing. When I met their parents and grandparents in 1984, we had rich conversations about belonging to lands through family and clan-based relations rather than nationalism. But we also talked about the histories of settler colonialism and racism that treated our ancestors quite differently. My family was proletarianized; theirs were targeted for extermination. When Black Americans were fighting against white supremacy in Shreveport and elsewhere, they were doing so against the ongoing racist infrastructures of enslavement. These conversations and contexts have been fundamental to how I think about privilege, responsibility, and accountability.

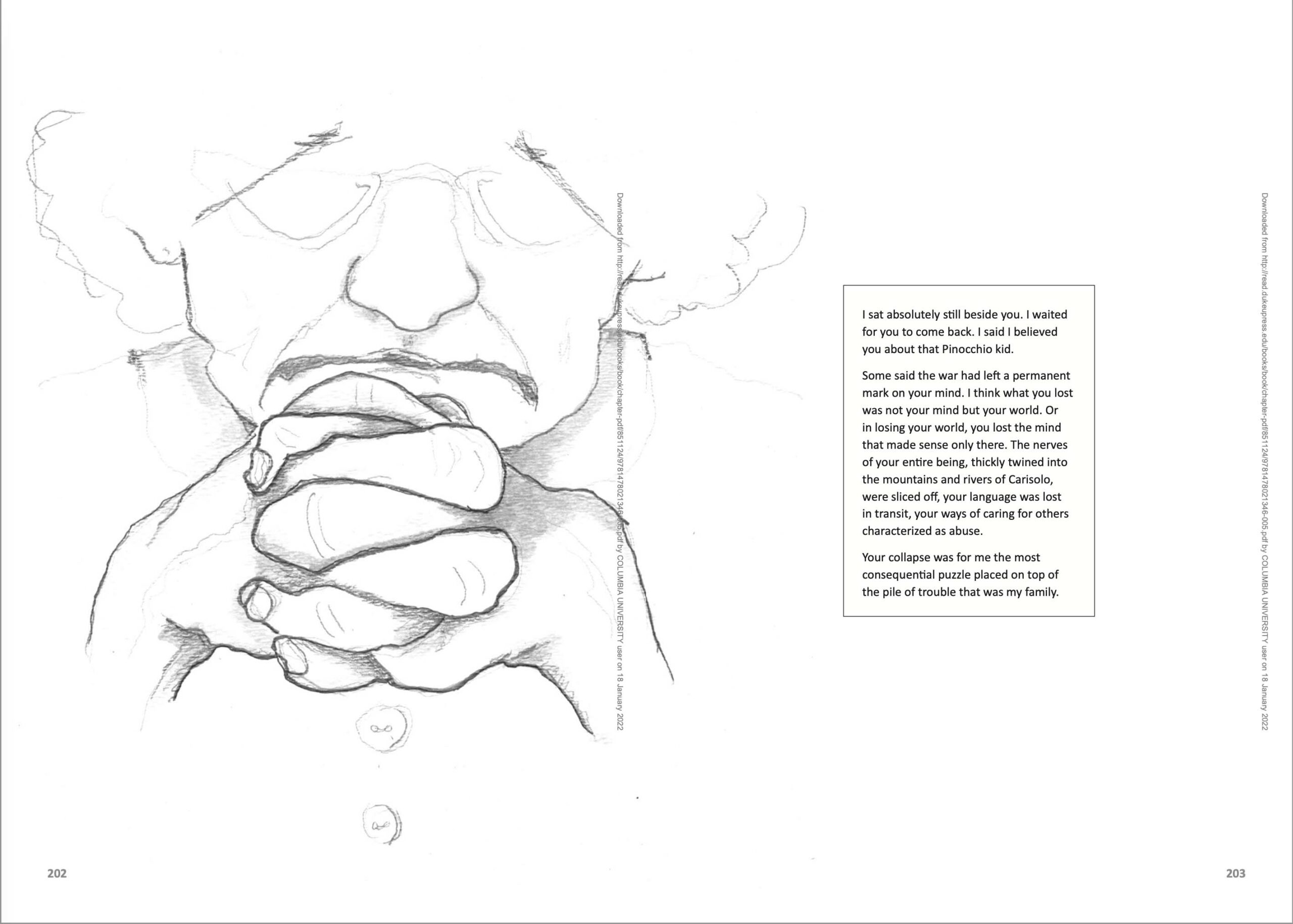

The Inheritance ends with a text box that says, “Inheritance doesn’t come from the past. Inheritance is the place we are given in the present in a world structured to care for the existence of some and not of others. My Gramma offered me an avenue into this insight. It took many others to force me to begin to use it.” Gramma lies at the heart of how I think about accountability and privilege and how I try to stage that thought in The Inheritance. I was hoping that readers would identify with the drama of my grandmother, feel for how she didn’t merely lose a place as she lost a world when she was uprooted from the village. Her language didn’t make any sense anymore; nobody spoke Ladin in the U.S. Her practices of care no longer worked or were valued. I wanted her Ambrosi story, the story of another family from the village, to stand as the ethical center of the Povinelli story. I wanted readers to feel, like we felt as little kids, that dispossession is both a psychic and social dislocation. But, as the last paragraph of the book says, she only offered me an avenue to understand the broad implications of the dislocations of dispossession. To really understand the ethics and politics of Gramma’s story was to understand it relative to different routes that sedimented from different kinds of ongoing dispossession.

To return to the beginning of our conversation: how do we interrupt the personalization and individualization of history based on DNA capitalism? “I thought I was but now I know that I am”? How do we understand inheritance as a sedimentation of values into bodies and landscapes? Ultimately, I hope that white people reading might, might, as they move from the drama of Gramma to the racialized worlds Little Elizabeth was actually living, be prompted to de-dramatize their personal histories of inheritance by placing them in the ancestral present. Will you treat your ancestry as some precious heirloom or are you going to use it to fully understand the world in which that ancestry is located?