I’m a sucker for a good performance. I’ll endure sore feet, plastic cups of cloying wine, and poets who read double their allotted time, all for a chance at experiencing those moments of potential meaning and feeling that become available in listening to a poet like Laura Henriksen read.

I first encountered Laura’s poetry at a reading at Molasses Books in Bushwick: standing room only, everyone holding their winter coats, pressed tight against the steamed-up windows. There was no mic until an audience member provided one spontaneously, miraculously; the stage was a corner of the room. The crowd hadn’t come for frills. We were interested, as Laura describes, in what happens when bodies gather to “hear each other listen.”

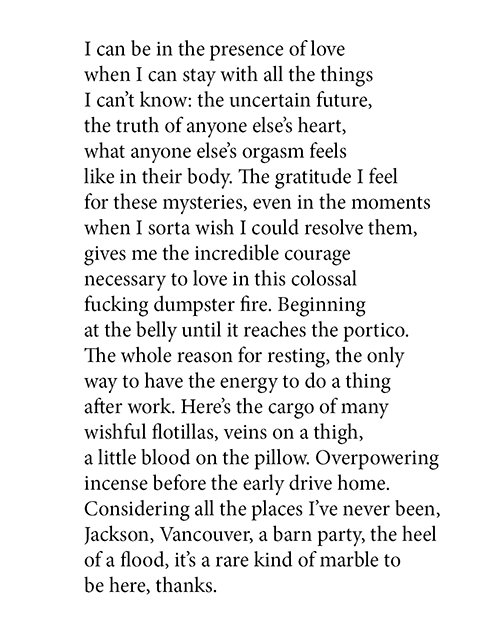

“Laura’s Desires,” the eponymous long poem of the forthcoming Laura’s Desires (Nightboat, March 2024) examines bodies and how they gather–in subway cars and movie theaters, on camping trips and at living room sex parties. The poem manages to create on the page the same spaces of possibility that I seek at an in-person reading. Encounters between the speaker and lovers, friends, strangers, art, and the natural world provide sustained and fleeting moments of proof that

Permanence

in intimacy is an unnecessary goal

since each intimate exchange in some

way forever alters all participants

regardless of what shapes they go

on to maintain between them.

In this interview, Laura and I discuss oceanic selfhood, unstable desires, and embracing imperfect interpretation.

Stella Harris: I want to start by asking you about the “I” of this poem. Lately I’ve been interested in discussions with poets regarding their “I.” Some favorites of mine have been Maggie Millner on LARB Radio Hour and Ama Codjoe and Solmaz Sharif on Between the Covers. I am especially curious about the “I” here given the poem’s use of the name Laura, as well as the speaker’s obsession with the impossibility of locating a stagnant or true self, and the alternating terror, freedom, and ambivalence that this impossibility brings her. Can you start by discussing this poem’s speaker, this poem’s self? Is it important to you that readers take seriously the distinction between the speaker’s perspective and your own?

Laura Henriksen: It’s interesting; I teach writing at Pratt, and I do the thing that people always do of going into workshops and saying, We’re never going to confuse the “I” of the piece with the people in class; we’re always going to be really clear that these are different; they’re coming from different places, and we’re not going to mistakenly place one directly on top of the other as if it were just one circle of a voice. I do that to create a space where there is a little bit of distance to think about the work together in a way that has a kind of criticality and spaciousness. At the same time, it’s not that simple, and in this particular work, the “I” is just so my own “I.”

In a previous version of the poem, I had experimented with including things that were just straight up lies, as a way to test, How do I feel about writing this poem where it seems so much like it is me? Then gradually, I realized, Well, it really, really is me. And I had to take all of the lies out.

They were all joke lies, little lies, lies about seeing movies that I’ve never seen–this kind of separating myself from the speaker of the poem. And then, as it got closer to publication, I got uncomfortable with those moments where there wasn’t a transparent relationship between my experience and the “I” in the poem.

Do you follow the really wonderful poet Angel Dominguez’s Instagram meme account?

SH: Yes!

LH: I saw one today, the Maury meme that’s like, “when the workshop thinks the speaker of the poem is the poet,” and I was returning to how much this is a thing that we learn and that is so often true: that it is so necessary to have a kind of spaciousness between the two. But then there are the ways in which in [this poem] I feel like the spaces are touching; they’re touching the whole time.

Yet even in saying that, [“Laura’s Desires”] is so much about the impossibility of any kind of stable and consistent speaker or voice or narrator or self. I’m interested in the incredible complexity of this consciousness that is receiving information and responding to it moving across time, and the ways in which this unified consciousness is absolutely, fundamentally part of our experience of being in the world and has memories and moves forward and has a temporal continuity. And then all of the ways in which it is so much more strange and complicated than that.

I think that’s even part of why I was interested in bringing the name Laura into the poem in so many different ways. The “Laura’s Desires” of the title is from this old porno film where Laura is the main character. So simultaneously the title is both meant to be pointing towards me, Laura Henriksen, and my desires, and then this fictional Laura figure that I encountered in the movie–who even in the space of the movie is also reaching out towards Laura Mulvey. Bette Gordon included the poster in Variety as a kind of homage or nod to the centrality of Mulvey’s work to the film. I was interested in having a Laura that points in a lot of different directions, that makes room for Petrarch’s Laura or Laura Palmer, so that even a poem called “Laura’s Desires” that would appear to have a direct relationship to an exploration of my own desires is also thinking about the desires of many other possible Lauras.

I feel like that interest [in evoking multiple Laura’s] evolved over time, too, insofar as the original version of the poem was significantly less personal. It was shorter, and I was often evading any actual reflections on my own desires–social, romantic, sexual; all of that was just sort of outside of the poem. It was still an investigation of the possibility of desire or the experience of desire, but not really the content of my own desires.

I was so nervous to write something with this level of intimacy and directness, where I am disclosing so much about my own experience and life and wishes and desires. For a long time, the only way that I could even write it was by having this fantasy that nobody would ever read it. If that were the case, then I could say this, then I could articulate this, I could admit this, describe this. That was the only way to make that kind of self-disclosure possible: if I was just speaking it to myself, or to no one, into a kind of void or like, my own room.

I was able to get comfortable with such a direct “I” in the idea that it was an “I” speaking to no one, which allowed it to become an “I” that speaks in a different kind of way. It’s taken such a particular welcoming of vulnerability to make a space where the “I” has this circular relationship, where the “I” of the poem and the “I” of Laura…it’s just one “I.” It’s one big “I,” to the extent that one big “I” is ever possible.

SH: You mention the comfort of speaking to no one, that in being able to have an “I” that is speaking to no one, it lets you go somewhere else as a poet. At the same time, there are many moments in your poetry in which the speaker of the poem struggles to understand if a self is possible outside of articulation or performance.

Throughout “Laura’s Desire,” for example, the speaker wonders, “What do I do when I’m not evaluating?” or “When do I ever stop being myself? Where do I go when I’m putting on a show, when I’m not performing?” She also mentions the unexpected pleasure that she finds in reading the poem to other people, that she can’t stop reading it to other people any chance she gets.

For you, what is the function of expressing one’s desires through language? What happens in that kind of utterance?

LH: I remember long before I wrote this poem, when I was writing poems that felt a lot more evasive of my own life, or for which I didn’t find it necessary to offer any details of my life particularly, I was still being called a confessional poet in a way I experienced as very dismissive. I remember being confused by this label and confused by my own reaction to it and why I found it offensive, why it made me feel critiqued in a way. Gradually I got to a place of thinking, well, maybe I can have a different relationship to being understood in this way, and maybe also find a different criticality in analyzing why someone might categorize a poem as “confessional” or not.

I also talk in the poem about the idea that I’m writing a poem and that, through this process, I will finally figure out what my desires are. Through the attempt to articulate a desire, I was also intending to figure out in that articulation what the desire even is, what its contents are. I feel like that’s so much connected to the possibility of a self as well: if you could figure out what you really wanted, would that mean you now know who you really are? Or something like that. And then in that search, it was necessary for me to start to recognize that this really wanted thing, this fundamental desire that would explain all of my choices and set me on a path, it just wasn’t going to be like that. It’s like expecting to drop onto ground that is sturdy, that can be traveled over in a straight line, but instead falling into water, a body so much more amorphous and ambiguous and shifting. And so I am interested in finding ways to be in the oceanic space of a desire that isn’t stable, and of a self that is also not stable

That this process was happening in language was also really fascinating. I was trying to make the spaces where I could begin to imagine or express feelings that were always exceeding my grammar, such that simultaneously it was possible to get closer to the wet heart of desire, while also recognizing that there was no heart, no central pump, nothing to point to and declare, here I am and here is what I want.

I think that is also connected to my having to take out all of the parts of the poem that were lies. As much as the poem is invested in exploring the possibility of freedom or the space for doubt, within all of these things, there’s a very ongoing question about what it means to tell the truth, to be true, or to know something, even as that something is always changing, is capacious and weird enough to hold everything and be nothing.

SH: I encountered this poem for the first time hearing you read it aloud. Your voice very much struck me, and it was in my head when I later returned to the poem. As I read, I remember thinking, Oh, this would land really well with a crowd, or Wow, I wonder how she’d approach reading this line, this line break, the intonation of this word, this syllable. I was almost looking for your embodied voice when reading your voice on the page. Hearing you read the poem before reading it myself fundamentally shaped my experience of it.

Do you consider the act of reading your poems to people while writing them? Does the anticipation of sharing your words out loud influence the process of writing them?

It is an interesting and complicated kind of pleasure that I experience from reading this poem, or sharing this poem, because it is totally bathed in nervousness; it feels like an incredibly risky thing to do every time. I feel grateful to get to live in a way where I can pretty regularly do things that feel pretty risky, such as reading a poem that has so much vulnerability in it. And then of course I have to ask, what do I think I’m risking, you know, it’s a poetry reading? But I think the risk has to do with understanding myself in a particular way, and then making a decision to complicate or disrupt that understanding, to shift my own perception of myself being perceived.

At that reading at Molasses where we met, for example, I was so nervous to read. I’d never read those sections of the poem before. They were very new and intimate and personal and sincere and involved talking about a lot of things that I find challenging and scary to talk about. I think, in attempting to enter those feelings in a public way, to resist my personal proclivity towards overvaluing a kind of privacy, I am hoping to invite a different kind of connection and understanding in ways that are both personal and social, in ways that I want to believe are potentially transformative.

I’ve basically organized my life around a belief that spaces where people read poems to each other are potentially transformative, and often actually transformative, and that something particular and exceptional happens in the space of people listening together to someone, a friend or a stranger, offering words that they wrote in this area of language that is poetry, where meaning is potentially fresh and renewed each time it’s uttered, or each time it’s heard. I have a very profound dedication to this particular kind of social space and what can happen there. And also, I find it to be extremely challenging.

For a long time, when I was becoming more involved with active poetry community, I couldn’t bear to read my poems in public. I felt like a spectacle in a way that was totally agonizing to me. I didn’t want my poems to be so directly connected to my embodied presence on a stage. The process of developing a relationship to public performance was largely made possible by my experience of being again and again transformed and transported by other people reading. Hearing someone with their embodied voice speak their words to me impacted my capacity to connect with different poems. Still, it continues to be something that I don’t find casual at all, that I find really scary–in a way that is fun and sexy and exciting.

SH: I am curious about what the revision process looks for this piece, especially given its length–both revision in general, but also specifically in relation to pacing and movement.

My experience of the poem was characterized by these delightful, surprising moments in which the speaker is considering sprawling, abstract questions of theory and art, and she is allowing herself to take herself seriously enough to think about these kinds of things, to dwell on them. And then she moves–she goes from this sweeping wonder to quotidian observations and experiences with her friends and her romantic partners and sex and very personal daily habits and routines and commuting on the subway. She moves between and across these moments in ways that feel natural yet effective, intentional yet unstaged.

I understand her as a kind of daydreamer–someone who sits and thinks and lets herself go all the way up. And then she reigns herself back in to do the laundry. But she doesn’t necessarily separate it–she doesn’t necessarily separate like, the cinematic Nan Goldin meaning-making from the dirty sock in front of her. It’s both: it’s turning, but it’s never actually abandoning the other thing.

All that is to say, I was wondering if that kind of turning comes naturally to you, and how much you’re thinking about that. I’m also interested in your process of entering and reentering the space of the poem when you’re writing and revising something of this length.

LH: It makes me feel so glad to hear that that was a core part of your experience of the poem, because it is central to me as well. I’m very invested in both exploring and also participating in a kind of feminist analysis, and one thing that has been really important for my thinking and being in the world through my reading of different feminist thinkers who have offered so much to my life, like Angela Davis, is a careful attention to connection all the time–to not making the mistake of thinking that lots of different areas of one’s life, or the world, are these separate pieces that are each sort of operating in their own sphere, but instead, always understanding the ways in which flows of power and possibility are moving through all of them in this way where there’s constant connection and touching.

Disrupting the idea of now I’m analyzing, and now I’m cleaning, is one of the things that I’m really invested in trying to remember throughout this poem: the ways in which these kinds of work are always informing each other, are the conditions of possibility for all of these other things to happen, that their relationship is fundamental, it’s in there from the beginning. It is intentional in the sense that, for me as a reader, it is a refreshing thing to get to move through these different areas and see these connections and also see these differences. And I’m also not trying to flatten them by saying they’re connected; I recognize that they’re fundamentally different, that reading philosophy and doing the laundry and having sex are each different experiences, qualitatively and in other ways as well. I want to make room for that in the poem, too.

Then there is the editing process to bring these things together. It’s such a weird poem, because it is so long, and I wrote it over such a long period of time, but not in order. It is a very collaged piece of writing where a lot of the shifts do happen in an organic way, where I can let my attention move in the ways that it’s going to move and trust that the connections are there. There’s also a lot of going back in and growing apart or shifting apart, and so much of that had to do with my astonishingly brilliant and generous editor at Nightboat, the wonderful poet Caelan Ernest, who has a really beautiful book that just came out called Nightmode. They were so helpful in figuring out the ways that [these moments] could grow, that there’s a deepening that is possible.

That’s actually a huge perk, in my experience, of having the “I” in this poem be so close to my own “I.” It hasn’t been like, How do I get back into the headspace of this poem? or How do I find this voice again? It has been much more the opposite, much more, How do I write something that’s not part of “Laura’s Desires?”.

As I was writing this poem, everything, everything returned to it. It was such a relief to just be editing it and accepting, This is where I am at, and this is the writing that I’m thinking about and continuing to do. It felt surprisingly possible to edit this poem, other than needing to not get too confused when, for example, lines are next to each other that were actually written years apart. There is a particular wildness of a poem with that kind of temporality, that sprawling messy time, and the experience of moving through what kinds of openings and shifts and repetitions can happen.

SH: You bring up Angela Davis and other influences that make their way into your work. That is another striking characteristic of the poem and a core part for me as a reader–how you are able to bring in so many people and their work and lives into your writing. You’re in conversation with Bette Gordon, Kathy Acker, Nan Goldin, Otto Preminger, Laura Mulvey, Elaine Scarry, Simone Weil, Ludwig Wittengenstein, Kanye West, Nicki Minaj, Megan the Stallion, Cardi B., Fanny Howe, Geoffrey Shugen Arnoldi, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Audre Lorde, and I’m sure I’m missing others. You manage to bring in all these voices, all while allowing the poem to suggest, critique, admit, wonder, and, obviously, desire, something of its own. On an artistic level, on a political level, how do you approach the process of citation?

LH: In many ways, I’ve always felt, more than a writer, more than anything else, like a reader. That is such a central way that I organize my experience of being in the world. In many ways, it felt like a relief to be able to be openly thinking about these other writers that I was already always thinking about.

Sometimes I felt, not so much worried about whether or not I would be able to make my own offering or reflect on something original or different, but rather, that I had to find a way to be okay with the possibility that I was going to be wrong sometimes, that I was going to misread things. There are definitely moments where I had to accept, This is the offering that I’m making of this Simone Weil quote, but I don’t know what other people may [find] who have a different relationship to her, to her thinking. I think there’s lots of close reading that I do that’s probably pretty debatable. Finding the space to be open, to know that what I will get from something that I read or something that I am invested in will just be what I am getting from it, and that there’s all these different ways in which I could be mistaken, or I could return to it later and experience something totally different…finding a way to be comfortable with that was really interesting.

So often, when you’re engaging in this process of citation, I think there’s a desire to be right, to make a point that is true, or is accurate, to be the one who is saying the thing that is the truth. Finding ways to be open, to let things be questions or let things be openings to explore other things was really fascinating, in the way of writing something that is also a real act of reading as well.

SH: At least in my experience, I think that there’s an idea within the digital or social media landscape that your true self is supposed to be reflected by everything you put out there, especially online. There is a feeling that, not only is it all permanent, but also, it’s going to have all these audiences you never could have imagined, and you better have gotten it right, because it’s out there. That’s the you that’s out there. So I admire that you manage to keep that openness.

LH: There were some wonderful friends who helped me along the way with editing. They would point to moments and say, “It really feels like you’re covering your bases here.” There is a particular kind of vulnerability of being like, Ok, I’m not going to invest this time trying to make sure that every possible valence is addressed. Instead, I will just try, with all of the integrity that I have, to approach these things that I’m so deeply concerned about, and then from that, offer what I have in the most humble and vulnerable way that I know how: in writing a long poem about what I want.