We are thrilled to feature an excerpt from editor-at-large Karen Tongson’s new book, Normporn: Queer Viewers and the TV That Soothes Us, which will be published by New York University Press on November 7, 2023. The following section is from Chapter 2, “An Intermezzo on Alternatives: From the 1990s to Normaling and Normcore.”

New to You

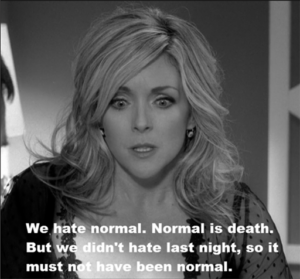

In the penultimate season of 30 Rock (2012), the sitcom’s resident kinkmeisters and genderqueer lovers, Jenna and Paul, are faced with a profound sexual crisis.1 After chatting about their day, they pass out fully clothed, nestled together beneath an afghan. Unable to accept this egregious lapse into long-term companionship, Jenna and Paul conclude that “normaling” must be a “whole new fetish,” a heretofore undiscovered playground of genuine perversity.

Comedy writers like Tina Fey and her team of 30 Rock scribes were prescient enough to comment on the fact that “normaling” was becoming a thing as early as 2012. Indeed, the televisual landscape was littered with references to a “new normal,” including a short-lived Ryan Murphy production about two gay men and their surrogate. As sitcoms like 30 Rock (2006–2013) and The New Normal (2012–2013) make apparent, all the hoopla about these purportedly “new” varieties of normalcy in the early teens were bound up with the sense that queer lives had been absorbed into the matrimonial and reproductive matrix.2

Meanwhile, scholars and cultural observers argued that heterosexuality itself—the purported baseline for normalcy—has become more flexible.3 Gay marriage has been legal across the land (though it’s imperiled by an overreaching Supreme Court as I write this) since Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015. Queer folks in all configurations have popped out “gaybies” left and right, and self-identified “queers” have been complicit in gentrifying urban neighborhoods all over the world for thirty years. Meanwhile lifelong cis-heterosexuals are now, and really have been since the late 1990s, officially allowed to call themselves queer. If the 1990s were about imagining the possibility that “we are all queer,” the postmillennial period between 2008 and 2016 told it to us straight: we are all, in fact, normal.4

Within two years of Jenna and Paul’s discovery of “normaling” on 30 Rock, life—or at least the New York Times version of it—began to imitate art. In 2014, a new lifestyle trend called “normcore” caught the eye of fashion observers from London to New York to Los Angeles. Trend-forecasted in the Times’ words by “a theoretically minded” group of brand consultants at a company called K-Hole in New York, normcore eschewed both couture and fashion-forward street trends to embrace off-the-rack basics: untrendy clothes easily sourced from big box shops or free corporate giveaways, which suburban tourists might wear unwittingly, and definitely unironically, to Times Square.5

K-Hole, a quintet of graduates from RISD and Brown University, introduced normcore to the marketing world with a forty-page white paper, which was also a manifesto expounding upon the “difference-seeking” and increasingly niched patterns of consumption and behavior among young trendsetters. Titled “Youth Mode: A Report on Freedom,”6 the report presented normcore as the next edge, or more precisely, the no edge.

K-Hole open their position paper (or in branding parlance, their “trend report”) by reevaluating the developmental lifecycle as it unfolds through the logic of cultural capital. I quote here at length:

It used to be possible to be special—to sustain unique differences through time, relative to a certain sense of audience. As long as you were different from the people around you, you were safe. But the Internet and globalization fucked this up for everyone. In the same way that a video goes viral, so does potentially anything. . . . The assertion of individuality is a rite of passage, but generational branding strips youth of this agency. Belonging to your generation becomes an inescapable truth—you’re a Scorpio whether you believe in astrology or not. At the same time, responsibility for generational behavior is partial at the max. (“It’s not you, it’s your whole generation.”) For a while, age came wrapped up in a bundle of social expectations. But when Boomerang kids return to their parents’ Empty Nests and retirement fades into the horizon, the bond between social expectations and age begins to dissolve. We’re left using technological aptitude to divide the olds from the youngs—even though moms get addicted to Candy Crush, too. Demography is dead, yet marketers will quietly invent another generation on demand. Clients are desperate to adapt. But to what? Generational linearity is gone.

AN AGELESS YOUTH DEMANDS EMANCIPATION7

Filled with sweeping generalizations, K-Hole’s white paper makes facile transitions between eras and generations, with a mix of some critical reflection about the negative impact of “globalization.” In short, technology, specifically “the Internet,” has made it so that differentiating one’s self is pretty much impossible. Typologies as disparate as generational branding and astrology (though implicitly these are just stand-ins for the many other marketing niches and demographic strategies available) have reduced everyone into lumpen masses. Not only are individuals no longer special, but the mere idea of specialness—the bread and butter of advertising and millennial capitalism—is off the table. “Clients,” meaning brands and other corporate entities, are at a loss for how to market amid this apparent loss of neat generational distinctions and the expansion of youth cultures and tastes to include the olds, or those “moms addicted to Candy Crush.” And yet, one of the first conclusions at which these purveyors of normcore arrive is recognizably almost queer: “an ageless youth demands emancipation.”

Queer writers and thinkers as far apart in era, style, and orientation as Oscar Wilde to Jack Halberstam, with plenty of subtler pivot points in between, have relied upon the stubborn attachment to youth and an antinormative relationship to developmental time—birth, marriage, children, death—to theorize queer difference, and ultimately queer emancipation. This emancipation, at least in a strand of queer theory from the last thirty years or so, has been routed through the subcultural. This is the gist of the argument in Halberstam’s A Queer Time and Place, and much of his oeuvre from that point on, which contrasts “normative time” and space with the subcultural undoing of generational propriety.

In his critique of David Harvey, for example, Halberstam catalogs some of those who purportedly “opt out” of living in normative time and space, and thus also “the logic of capitalist accumulation: here we could consider ravers, club kids, HIV-positive barebackers, rent boys, sex workers, homeless people, drug dealers, and the unemployed.”8 Halberstam then incorporates this motley assortment of opt-outers—bracketing aside the fact that perhaps the unhoused and the unemployed have never been given the opportunity to opt in—as potential “queer subjects.” Obviously, this notion of the queer outlaws who extract themselves from the demands of a plodding normative life is a captivating one, and has been since figures like Wilde were put on trial for their perverse relationship to age and desire.

I gently critique this line of argumentation in Relocations, my first book, largely on the grounds of its sustained attachment to subculture, and eventually take issue with it casting its many avatars, including an atavistic relationship to “the wild,” as an unproblematic and necessary site for queer politics and cultural resistance.9 As I and many others argued then, the discourse about anti-normativity still thriving within subcultures, especially in the vein Halberstam argued, presupposes one’s ability to opt in and out of normative demands, while expecting the continued, unadulterated existence of subcultural formations, even formations named outside of culture that are purportedly anarchic or “wild.”

As we’ve come to learn, punctuated by the time the GAP began selling Lesbian Avengers T-shirts during pride season in 2021, this isn’t really the case anymore. The aesthetic and political economic framing of queer life as perpetually outside and against a mainstream still fails to acknowledge how fundamentally interwoven, and indeed complicit, queerness has become with mainstream, corporate political economies since at least the 1990s, largely by becoming normativity’s edge play since that era.

Obviously, I’m nowhere close to being the first person, nor am I the only queer theorist (whatever that is anymore), to point out the shiftiness of norms and normalcy.10 One of my favorite writers and intellectual touchstones, Lauren Berlant, has written volumes about the caginess of norms, constituted as they are by our most wily, if not necessarily wild, desires. “Our” desires are wily because a sense of what’s ours is always imbricated with what is “theirs”—with a collective unconscious as well as consciousness about certain structural, formal, generic, and nationalist impulses and demands.11

To break this down for any general readers who may have just wandered in looking for some stuff about TV shows: norms, though they are meant to give the illusion of stability, are actually always shifting, absorbing, and incorporating those things that seem to exist outside of them—especially “others” of all stripes, from exiles to perverts to gender traitors and queers. This is why norms are so cagey.

What is “normal,” then? The standards for normalcy made available to us at any given historical moment don’t remain the same across time, hence all the hullabaloo about a “new normal” every five years or so. This makes it difficult to argue that what is putatively “queer” is simply something that is aberrant or abnormal, because the normal, like late capitalism itself, is cravenly adaptable and adept at tapping into our desires.

Notes

1 Paul L’astnamé, played by former SNL cast member Will Forte, is not only a female impersonator by trade, but his signature drag persona is Jenna Maroney (Jane Krakowski’s character on the show, who is a narcissistic comedic actress on an SNL-style variety show).

2 On the heels of these comedies parrying with gay normalcy, Honey Maid graham crackers released an ad depicting gay fatherhood as “wholesome.” This inspired GLAAD’s approval and incited relatively little controversy given some of the flare-ups that occurred in the 1990s about any form of gay representation. GLAAD’s coverage of this treacly TV moment is archived here: https://www.glaad.org/blog/ video-honey-maids-wholesome-ad-includes-gay-dads.

3 See Jack Halberstam’s chapter on “heteroflexibility” in Gaga Feminism: Sex, Gender, and the End of Normal (New York: Beacon Press, 2013).

4 Not all of us, of course. My arch use of the royal “we” here is not to say that everyone has equal access to the status of “normalcy” (which has always been reserved for a primarily white, cis bourgeoisie). This is obviously far from the case, and increasingly so as we are consumed by the metastases of end-stage capitalism. But insofar as this book focuses on the question of what is “representable,” especially in the televisual world driven by ad dollars and the consumer capital of the middle and affluent classes (or those who aspire to join them), the “we” signals precisely those among us—like academics and cultural critics—who have both the cultural and financial privilege to fret about our relationship to normalcy to begin with.

5 The better part of a decade later, normcore has evolved into more niche regional versions like the NYC-based Zizmorcore (https://www.thecut.com/article/zizmorcore-nyc-fashion-trend.html) and Cheugy, which was purportedly spawned in Beverly Hills by a tween.

6 K-Hole, “Youth Mode: A Report on Freedom” (October 2013), the original white paper that spawned normcore, can be found here: http:// khole.net/issues/youth-mode/.

7 Ibid. Emphasis in original.

8 Jack Halberstam, A Queer Time and Place (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 10.

9 See Jack Halberstam’s Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire (Durham, NC:

Duke University Press, 2020), which in effect rebrands “wildness” in its many guises, with an emphasis on its queer iterations, as the oppositional force to normativity. “Wildness” as a feature of queerness, according to Halberstam, is what shines a light on what underlies the normative taxonomies of sexuality.

10 Michael Warner’s classic The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life (New York: Free Press, 1999) disabused a broader readership of the idea that all same-sex relationships could be construed as nonnormative, especially with the centering of gay marriage in mainstream activist agendas. In 2003, Lisa Duggan established the term “homonormativity” to describe this process and its increasing dominance and circulation in LGBT “equality” discourse. As she writes in The Twilight of Equality?: Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics, and the Attack on Democracy (New York: Beacon Press, 2003): “the new homonormativiity … is a politics that does not contest dominant heteronormativity assumptions and institutions but upholds and sustains them while promising the possibility of a demobilized gay culture anchored in domesticity and consumption” (50, italics in original).

11 Berlant has explored these questions and tracked the entwinement of norms and affect across several popular forms in the U.S. in books like The Queen of America Goes to Washington City (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997), The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), and the short primer Desire/Love (Brooklyn, NY: Punctum Books, 2012). My own efforts at classification, taxonomy, and generic specification here are deeply inspired by the meticulous work they have undertaken to describe the processes of normalization as they are routed through desire and “national sentimentality” in forms like the romantic comedy, the melodramatic novel, and political theater itself.