Two boys guide white stallions across gray and brown brushstrokes. Pablo Picasso’s boy is naked, and Enrique Martínez Celaya’s, painted 104 years later, has no face. One must be Job, and the other, Jonah. Storm clouds silver the canvases from left to right. Picasso died when I was five, but I’ve met Celaya. He named his Los Angeles studio “Whale & Star” and traded Picasso’s antiwar communism for a quiet Christianity. For some reason, his assistants asked me if I could connect him with art dealers. Art helps its makers find peace, but my son hedges his bets. He’s earning economics and English degrees and working on an application to Stanford Law. He says, “I’ll finish the novel once I’m set.” He loved the “Art Since 1900” class he took from a friend of mine at USC, where Celaya teaches—but tells me the humanities are dead. He plans a career in mergers and acquisitions. This third boy drives the girl with mascara eyes to the Getty Villa in his white minivan.

Julian Dashper did not make Painting of a Painting from the morphine he denied his body. Those paintings came later. This time, he stacked one square canvas on top of a second and used thin varnish or dirty turpentine to echo a third. The ghost image is hard to see, but when his pain needed treatment, the squares raged violet, and he paled quietly. The last time he visited, Julian hung Painting of a Painting from a nail hole in the dining room above the oak sideboard. He’d flown from Auckland with a film crew for a final performance. “The money’s from our rainy day fund,” he said, torn between legacies: art or family? I hugged Julian’s widow and son at a memorial in Brooklyn ten years after his death. Marie. Leo. I’d brought along my teenager, who’d been wearing yellow sweatpants in that film all those years ago. The three of us had walked past the Frank Lloyd Wright houses in Oak Park. Julian and I discussed an art critic from The New Zealand Herald. That man had denounced Julian’s art forty times. My son played with a stick.

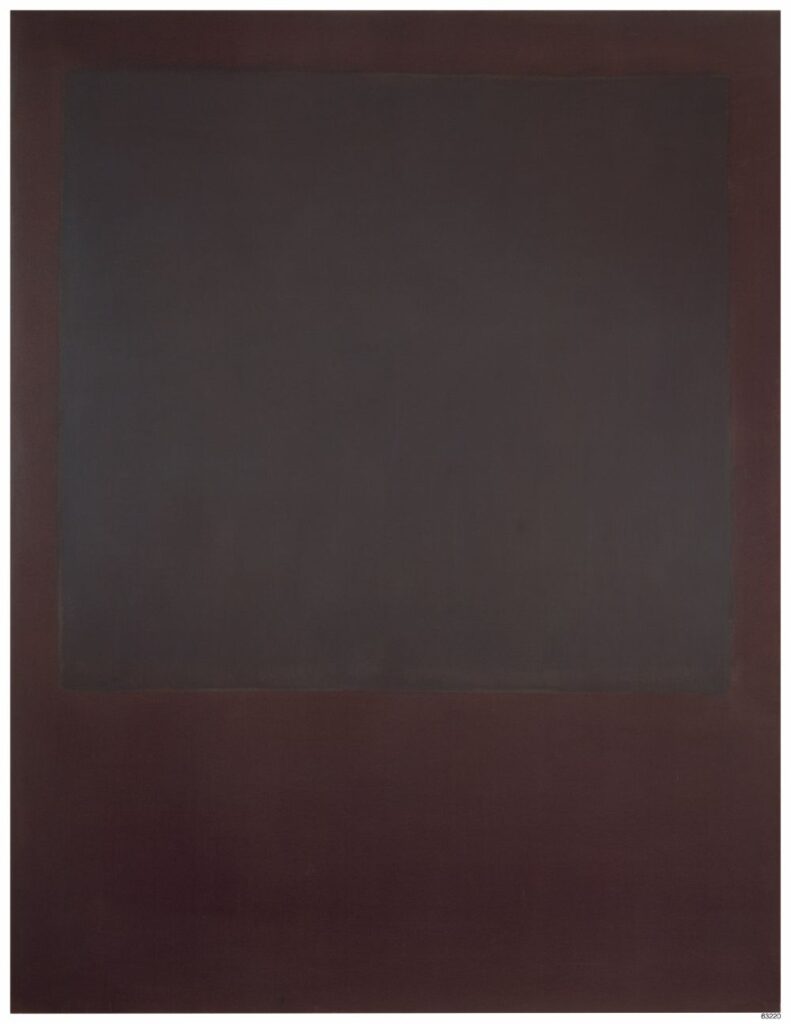

The Rothko puts me eighteen inches from losing myself. Two or three layers of oil brushed on canvas, a black-burgundy rectangle on a burgundy-black surface nearly square, almost hard-edged, thick, more reflective, less translucent, and two-thirds the picture. The contrasts, though slight, accelerate, become outsized, and slip away as certainty reverses. “The sublime is now,” he said. You think your kid could do that? So what. My wife and I stood in line as rain fell to see the Rothko retrospective at Fondation Louis Vuitton because someone said it would change my life. And because this is Paris, we are pinned between clouded smokers speaking French and, naturellement, water bottles are interdits past the metal detectors. There goes another carton of Knorr tomato soup jeté par les fenêtres. Rothko spoke four languages but not French.

Richard Serra’s sculpture Reading Cones is my beach book. Its double arcs run for fourteen feet and rust by design: Corten Weathering Steel, self-patinating. It’s a crusher. It put Joseph Gallo in a wheelchair after collapsing in a SoHo gallery. Gallo’s wife refused to speak to The New York Times. It’s now across the street, just a block from Lake Michigan. When my students and I spin around the sculpture, it holds our bodies like the Wave Swinger at the Illinois State Fair. We walk inside and smell piss but see Buckingham Fountain and the Frank Gehry bandshell: Hall of Mirrors. What to do with Gallo’s pain? Let’s ask Winckelmann if Laocoön’s suffering is still the highest form of beauty. Serra died this year. He’d come to talk to my class when I was a student in Austin, Texas. He said he’d just returned from Auschwitz. Afterward, in the rush, I said, I’ve been there, too. He pulled his hand away.