“It’s really blossoming now.” My sister texts me on her walk home from the hospital, where she runs one of the ventilator programs.

“Flowers?” I reply. It’s March 2020, the start of spring.

“Virus.”

A week later: “It’s really really bad. Lot of sick doctors and nurses getting placed on ventilators.” We switch from texting to phone, and she tells me about a sick ward that seems remote from my everyday life, 80 blocks south. This is before the around-the-clock sirens.

“I’m trying to focus on the small things. The pear trees.”

I look out my window and see creamy clouds of white up and down the Houston Street meridian. Are those pear trees? We hang up and I search the internet for “Manhattan pear.” I’m startled to find an interactive Street Tree Map published by the Parks Department, with seemingly every tree in the city pinpointed in a shade of brown or green. “The world’s most accurate and detailed map of a city’s street trees,” it was created by thousands of volunteers who measured trunks and logged GPS coordinates.

I am surrounded, it turns out, by Callery pears, one of the most common trees in the city. Clicking on the green dots, I read about the extraordinary “tree care activities” performed by anonymous “stewards.” Even now, when care is in such great demand. This week, a Callery on a nearby corner was “cleared of litter/waste” and “had flowers planted around.” To the dollar, I learn the value of the stormwater each tree intercepts, the energy it conserves.

By the late nineteenth century, the New York Commissioner of Health recognized that trees had sanitary value, from oxygenation to the shade they provide during the city’s sweltering summers. Tree-planting societies were founded; care for trees was care of the self. The Parks Department received city funds to take up the mission of cultivating public health. It was an uneven project: looking at the clusters on the Street Tree Map today, I see that my neighborhood, the West Village, has more than twice as many trees as Chinatown, kitty-corner on the map.

Plant Pandemic

Calleries were brought to the United States a century ago from Hubei, the Chinese province whose capital city is Wuhan. They were rootstocks and ornamentals, a second wave of pear immigration after the varieties that bore fleshy fruit. Pear trees have been cultivated for thousands of years in China. This supposed “gift of the gods” in The Odyssey made its way to ancient Europe via longstanding routes of earthly trade. Pears traveled well. They later sailed to the Americas with the colonizers, where they picked up a deadly oozing infection, fire blight—part of the inevitable traffic in disease that accompanies the movement of living things. People knew that trees got sick, but it wasn’t until the nineteenth century that fire blight was connected to a bacterium: the new germ theory held true for contagious plants as well as humans.

Pears began to be mass produced along with everything else in the nineteenth century. Industrial capitalism operates at a grand scale, and as rows of genetically identical pear trees were planted along the Pacific coast, they provided the ideal habitat for agricultural pandemics. Once fire blight entered an orchard, it raced from tree to tree, blackening branches and hiding in roots. And it traveled with pears back around the world in tins, as people everywhere developed a modern taste for sweet canned fruit.

Before diseased orchards began to be sprayed with streptomycin in the 1950s, plant scientists searched for immune species of pear, hoping to graft prized fruiting branches onto disease-resistant trunks. In the early 1900s, Frank Reimer ran the Southern Oregon Experiment Station, a “test orchard” in the town of Talent where he examined dozens of known pear varieties for evidence of blight immunity. Nearby in Medford, companies like Bear Creek, run by Harry and David Rosenberg—the Harry & David—were on their way to becoming international giants of Comice pear-growing as blight encroached in the Nineteen-teens.

When Reimer identified Pyrus calleryana as a resistant species in 1915, and one that was well-suited for the Pacific Northwest climate, he sent an urgent request to the Department of Agriculture in Washington D.C. for the launch of a collecting expedition to “the flowery kingdom”: China. At the time, the lone Callery pear in the United States could be found in the Harvard arboretum, grown from seeds collected in Hubei in 1908 by “plant explorer” Ernest Henry Wilson. But Reimer needed at least a hundred pounds of seeds, extracted from thousands of pears, for his industrial grafting plan.

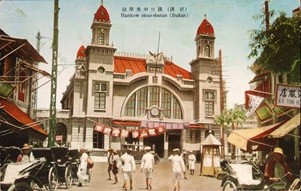

In 1916, the Department of Agriculture hired Dutch explorer Frank Meyer to return to Hubei to collect the roots and seeds of Callery pears, along with other potentially “economically important” plants. Meyer is now memorialized for the lemon he dispatched to the U.S. during a prior expedition to China in 1907. (The pear received its Western name in the nineteenth century from a missionary, Joseph Callery, who brought the species to France.) Meyer’s base this time would be Hankou (in his spelling, “Hankow”), the city that gave the “han” to Wuhan when it merged with two neighboring towns in 1926. The region had long been mined by Western explorers for its “plant wealth”—bought, stolen, and bartered.

On this trip, Meyer noted that he was chasing a new sort of botanical commodity. Not food, ornament, or human medicine, but disease-resistance; an immune understock for “foodstuff.” In one of the many letters he posted to the Office of Seed and Plant Introduction in D.C. during his two-year sojourn, Meyer marveled, “This disease-testing work has opened up an entirely new field for certain introductions from abroad!” But there was something self-defeating about the American agricultural project: botanical variation was introduced for the purpose of massification; new diseases hitchhiked along, spreading and evolving at lightning speed. Meyer commented in another letter, “The sooner the American people realize that one kind of a product cannot be grown everywhere and under all sorts of conditions, the better it will be.”

Hankou/Wuhan

When Manhattan “pauses” in mid-March, I learn what I can as an apartment-bound historian of science about the new coronavirus—not just its effects on humans, but its natural history. Andrew Liu’s “Chinese Virus,” World Market, published in n+1 before the end of the month, introduces me to Wuhan and cautions that natural history is inevitably peopled; it doesn’t exist outside the economy. In the 1980s, Liu explains, market liberalization, leading to more and faster commercial interchange and rising incomes, transformed local diets and the surrounding landscape. If it turns out to be true that the virus leapt into humans somewhere in the Wuhan region, in a market or mine, the chain was never so simple as bat—>person. It is more like a netting, all the “pathways of the 21st century global market” that connect Wuhan to everywhere else.

When my pandemic reading shifts to the Callery pear, I should not be surprised to find Wuhan there. And another slipstream of disease, arcing much further back, trailing centuries of transnational plant commerce. I spend the first part of April reading Meyer’s letters and field notes collected in South China Explorations, July 25, 1916-September 21, 1918. It was a period of constant, grinding human illness. Not just the irruption of the 1918 “Spanish” flu, but numberless endemic diseases with heaps of sequelae, and no pharmaceutical end yet available. Meyer went to Hubei province for fruit and cures. There is something discouraging about the way this biologist, this lover of variation, described the people there as “weeds” and “pests” for their experiences of universal plagues like syphilis and lice.

In the mountains whole villages are syphilitic; people without noses are often met with and syphilitic blindness and deafness are very common. In the inns the vermin is exceedingly plentiful and bloodthirsty and ordinary travellers have to sleep three abreast in one bedstead or on one broad bench and the stinkingly dirty bedcovers are kept in use until they fall to pieces. No wonder that 80% of the population suffers from all sorts of skin diseases, being inoculated by lice, fleas, and bedbuds [sic].

He admired certain aspects of the Hubei diet, the pickling and the soy products, but he labelled most of the population “nothing but human animals” for living on vegetables alone. He never documented any “wet markets” or exotic meats—or even anyone eating a fish.

Meyer foraged for the better part of two years in the mountains around Yichang (“Ichang”) and Jingmen (“Kingmen”), returning to the Hankow Hotel to prepare and ship specimens after the fruiting season. For brief periods he was laid up with his own illnesses, dysentery and “nervous prostration.” During the first part of 1918, he was confined to rooms in Yichang and Hankou by martial law, because of internal revolt (the Constitutional Protection War). World War I was raging abroad. He almost ran out of writing paper, which caused him great distress. His notes from those months mention looting and burning, “robber-bands and outlaws,” and soldiers ripping the hearts out of people’s bodies. He was later able to garden, and he read the same Whitman book over and over to “keep from going crazy.”

His loneliness is through-the-looking-glass from my own. I’m buried in an endless supply of text during lockdown and rarely outdoors; protesting hasn’t started yet. Meyer’s take on humanity is pessimistic and biased to the point of derangement, but some of his impressions from spring 1918 seem to have crystallized from the same cyclic fog of world uncertainty that now engulfs 2020. I start mailing postcards with quotes to my kids, who are in Berlin and California. It hasn’t occurred to me yet that I might not see them for six months, a year even, the longest we have ever been apart. One of them gets COVID. One of the postcards is lost.

“One cannot live for months in an atmosphere of suspension without feeling the effects.”

“We do not live ourselves anymore but we are being lived by uncontrollable forces.”

“One gets the feeling that one’s work is of not much account any longer and one gets that loose feeling of a homeless child in the street.”

The nights are hard.

In the first week of April, my phone rings and because it is a number from Oregon, where I grew up, I answer it. Maybe it is my school friend again, “checking in,” and she will tell me stories about goats in the yard and a motorboat in the river just across the street. But it’s an employee from Harry & David on the phone: Can they do anything for me? A friend who works for a digital ad auctioning company once showed me how it works on her laptop—how I was grouped into a particular audience based on my location, demographics, and browsing history. And then she clicked on a really funny tampon ad, the best and most feminist tampon video I had ever seen, and said “but this is for a younger target,” and I had that feeling of missing out, except that the ad was missing me—so I have a mental image of my data being bought and sold with “lightning speed.” I hadn’t thought about my phone number circulating, too, and the intimacy of this phone call, reaching me while I am still reading about pears online, disturbs me.

I ask my boyfriend (who goes by “any pronoun but he”) if she thinks these things are all connected. I’ve moved in with her for a month—this is before The Social Dilemma docudrama is released and everyone is talking about it. She has never lived with anyone before and we have never spent more than a few days together. “Chips”— she has started to call me this, for the same reason that we have started to drink diet Coke in the afternoon and fernet in the evening—“Shouldn’t you be working on something else?” We are eager for habit. When I pull the wool blanket over my lap in the small living room, it means I am “in my office.” We tell each other that our dogs are going to miss spending so much time together.

I order gift boxes for my kids. Harry & David ships to Germany: they were American mail-order pioneers, and still at it. In the 1920s, they learned how to “pre-cool” fruit after a harvest, to remove something lovely called “field heat” before packing, but that’s what has to happen for pears to make it all the way to Europe. I start to receive paper catalogs in the mail and I tear to the back pages to read the potted corporate history. If I am paying Harry & David to research this essay for me, and letting my gaze wander from Google Scholar to search engines where I elaborate a shadow database of myself, and if I otherwise rely on the diary of a Dutch explorer who hated Chinese people, I will learn more about predatory global capitalism than I will about Wuhan. And that is the point.

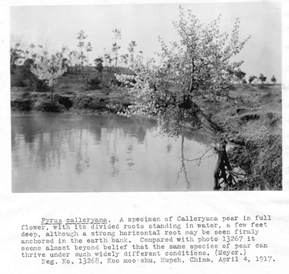

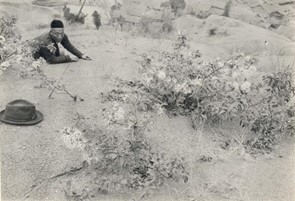

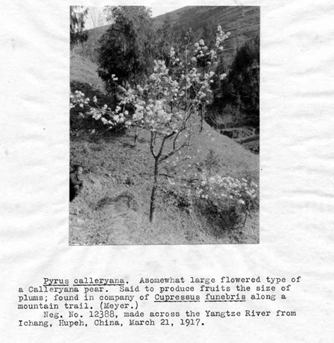

Meyer made several forays from Hankou into the hills to collect wild pear seeds between 1916 and 1918. Reimer joined him in Jingmen for a brief period the second autumn. Callery pears were “weedy” and could be found in almost any landscape, a trait Meyer admired in trees, at least.

Pyrus calleryana is simply a marvel. One finds it growing under all sorts of conditions; one time on dry, sterile mountain slopes; then again with its roots in standing water at the edge of a pond; sometimes in open pine forest, then again among scrub on blue-stone ledges in the burning sun; sometimes in low-bamboo jungle…and then again along the course of a fast flowing mountain stream or on the occasionally burned-over slope of a pebbly hill.

Although the trees “sprouted lustily,” they tended to be small and scattered rather than growing close together. The fruits were also small and sparse. These features made seed-collecting a painstaking process. After months in the field, Meyer would return to Hankou to carefully pack seeds, fruits, and twigs for shipping to Talent, to Harvard, and to another research station in Chico. When his packages reached the U.S., if they weren’t lost at sea, the “plant immigrants” were quarantined, even held in detention houses. Although Callery pears were recruited as orchard healthcare workers, an immigrant is an immigrant is an immigrant: they had to be checked for insects, mold, and disease themselves. All those long, hot days of hiking and harvesting by Meyer often ended with incineration. A life’s work.

Street Tree

On May 31, 1918, Meyer boarded a steamer in Hankou, heading to Shanghai where he planned to spend a month to escape the summer heat. He felt ill; one night he vomited and dreamed of seeing his father. On June 2, he disappeared from the ship. His body was later fished from the river and it was never discovered whether he had been pushed, fallen, or jumped.

Thousands of seeds made it across the ocean. And Reimer’s plan worked. Callery pear trees became rootstocks for Comice, Bosc, and other varieties; the Rosenberg brothers were saved. One hundred years later, my children open cardboard boxes, heavy with perfectly ripened fruit, a single pear wrapped in gold foil, a glint of rarity within mass-produced life.

The sociologist Georg Simmel, who died the same year as Meyer, published an essay at the end of his life “on the essence of culture” that opened with a meditation on the cultivation of pear trees. “The wild pear tree,” he wrote, “produces hard, sour fruit. That is as far as it can develop under the conditions of wild growth. At this point, human will and intelligence have intervened and, by a variety of means, have managed to make the tree produce the edible pear. That is to say, the tree has been ‘cultivated.’” He contrasted the human cultivation of latent traits in trees with culture, which he argued was proper only to people. Culture was external, an immersion in society and a continual adaptation to new styles and group forces. If the trunk of a pear tree “is made into a ship’s mast, this, too, is undoubtedly the work of culture,” but the cultivation of fruit from that same tree, he argued, was rather an expression of immanence.

Simmel turned out to be wrong, dangerously wrong, that nature and culture are separable, and that each plant contains a singular potential, perfectible by humans. Evolution is much more chaotic than that, and plants participate in the give and take of culture alongside people. Farmers organize orchards, and graft species to one another, to suit industry—the marketing of taste at a given moment. And still many aspects of pear-growing remain out of human control, emergent rather than immanent to plant life itself: pears migrate and hybridize with other varieties of their own accord; they are opportunistic; and they respond to culturally-induced environmental changes, including temperature and disease, with changes in their physical forms and interspecies relations.

In the 1950s, the Callery pear made a dramatic move out of the understory and into the boulevards of American cities and suburbs, when horticulturalists began to view it as a tree in its own right, rather than merely an orchard rootstock. Working in the postwar period, when “a broader interest in horticulture resulting from the development of suburbia” encouraged the mass planting of ornamentals, USDA scientist John Creech restaged Meyer and Reimer’s quest for a hardy pear tree. In his own “street tree study,” Creech grafted a Meyer-Reimer rootstock to a Callery scion (shoot or branch) from a later expedition to China. He named the resulting cultivar (cultivated variety) the Bradford, admiring its grow-anywhere abilities, its resilience to pollution, and most of all its profuse white blossoming at the very start of spring. The Bradford is the tree I see outside my window, on which my sister pins her happiness in March.

The Bradford variety of the Callery pear was “cloned by the gazillion,” says gardening journalist Adrian Higgins. “Like the cookie-cutter suburbs themselves, the Bradford pear would embody that quintessentially American idea of the goodness of mass-produced uniformity.” It stayed popular for many decades, even as aesthetic complaints about the tree mounted. Some people dislike the odor of the flowers, comparing it to chlorine; others call Calleries “the semen tree.” The branches break easily in storms; the tiny fruits of some varieties leave messes on the smooth poured concrete that pear trees now share with humans.

Unexpectedly, at the end of the twentieth century, the Callery pear became, as Higgins puts it, an “environmental time bomb” ready to explode. “We brought it to an alien environment, selected one for unnatural propagation and then fused genetically different individuals together. We planted it intensively across the entire continental United States, seeding its eventual spread.” Bradford scions with genetically different rootstocks are able to self-sow if the stock sends up a shoot; Bradfords also cross-pollinate with other varieties of Callery pear. By the 1990s, the Callery was dispersing exponentially across the continent, biologist Theresa Culley explains, “escaping” the cities and suburbs and moving into what “natural areas” remained. Its hardiness and its genetic diversity meant that it outcompeted most other plants.

What we hoped would be a remedy and a thing of beauty was rebranded a weed, an invasive species, an aggressive foreigner. A “Chinese Callery pear” devastating the “native” environment. Something viral.

What Survives

How calm and immobile the green dots seem on the map of street trees in New York. Some have nationalities: the Norway maple, the American basswood, the Japanese pagoda tree. I know the names of these trees and where they are planted, but not how they got there, or where the fruits and seeds will travel. It’s an irony of cartographic history: in Meyer’s day, dot maps were pin maps, designed to represent movement. A manager with a map on his office wall added and subtracted pins to show the accumulation of supplies—seeds maybe—or the movements of trains and salesmen, boats and explorers, throughout the week. But now we want to imagine the permanence of trees. In its weekly effort to keep isolated residents inhabited by the city, The New York Public Library circulates an email on May 11 offering a virtual walking tour of ten famous trees—“our most venerable and impressive landmarks.” Two are pears.

Surely the most memorable dot map published in spring 2020, and one truer to historical form, was “How the Virus Got Out.” An interactive feature in the online New York Times, the map opens with a close range view of the Hankou train station, across the street from the Huanan seafood market. A pink dot appears—hot pink—and then another. The dots multiply frantically. The image zooms out to the map of China, on which Wuhan is now a massive oozing boil. Another order of magnitude removed, we are shown international flight patterns. Dots teem from Wuhan: are they people or the virus? The credits explain that the image is rendered from the estimated movement of cell phones. Anonymized, made numberless—this is how a swarm is conjured. Weeks later, in the same paper, I read that the outbreak in my city was more likely seeded by tourists from Europe.

The way the street tree map is designed, viewers “can mark trees as favorites and share them with friends, and they can record their tree stewardship activities.” One Callery pear in particular is the darling of New York City, a Bradford that was found living beneath the rubble of the World Trade Center in 2001. Pyrus calleryana is simply a marvel. In September, I learn that the 9/11 Memorial gives a seedling from the “Survivor Tree” to “communities that have endured tragedy in recent years” as “a symbol of resiliency and hope.” Where to begin in 2020? But also: who wants a gift they already have in abundance, the gift of an “invasive” species?

Living memorials are as conflicted as military statues. I imagine giving a seedling to Talent, Oregon. “Here: try again.” Talent is one of the towns most ravaged by the unprecedented late summer wildfires and drones fly along Highway 99 in the aftermath. Pear research was moved to Medford Station in 1931, but I pore over the drone footage anyway, looking for the field where Reimer first recruited Callery pears from Hubei.

Perhaps another seedling to Minneapolis, to plant in the concrete at the corner where Cup Foods is located, where George Floyd was killed? The northern region is still too cold. Although climate change is making inroads, for now it’s one of the few environments where the Callery pear doesn’t grow. Not all violences can receive this commemoration.

And last but not least, a Survivor Tree seedling for Wuhan. “Take it back.” After a century of Callery pear commerce and public health, “We don’t know what to do with it.”

Sources

William Alley, “Cubby of Bear Creek and the Harry and David Story,” Southern Oregon Heritage 1, 3 (Winter 1995): 23-27.

John L. Creech, “Ornamental Plant Introduction—Building on the Past,” Arnoldia 33, 1 (1973): 13–25.

Teresa M. Culley, “The Rise and Fall of the Ornamental Callery Pear Tree,” Arnoldia 74, 3 (2017): 2-11.

Isabel Shipley Cunningham, “Frank Meyer, Agricultural Explorer,” Arnoldia 44, 3 (1984): 3-26.

Adrian Higgins, “Scientists Thought they had Created the Perfect Tree. But it became a Nightmare,” The Washington Post, 17 September 2018.

Heather McMillen, Lindsay K. Campbell, and Erika S. Svendsen, “Weighing values and risks of beloved invasive species: The case of the survivor tree and conflict management in urban green infrastructure,” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 40 (2019): 44-52.

Frank N. Meyer, South China Explorations: Typescript, July 25, 1916–September 21, 1918 (Washington, D.C.: National Agricultural Library, 1918), Available online at: https://archive.org/details/CAT10662165MeyerSouthChinaExplorations

F.C. Reimer, “A Promising New Pear Stock,” The Monthly Bulletin, California State Commission of Horticulture 5, 5 (1916): 166-171.

Georg Simmel, “On the Essence of Culture,” Simmel on Culture: Selected Writings, ed. David Frisby and Mike Featherstone (London: SAGE, 1997), 40-45.

Stephen Smith, “Vegetation: A Remedy for the Summer Heat of Cities,” Popular Science Monthly (February 1899): 433-450.

T. van der Zwet, N. Orolaza-Halbrendt, and W. Zeller, Fireblight: History, Biology, and Management (St. Paul: The American Phytopathological Society, 2012).