Age Sixteen

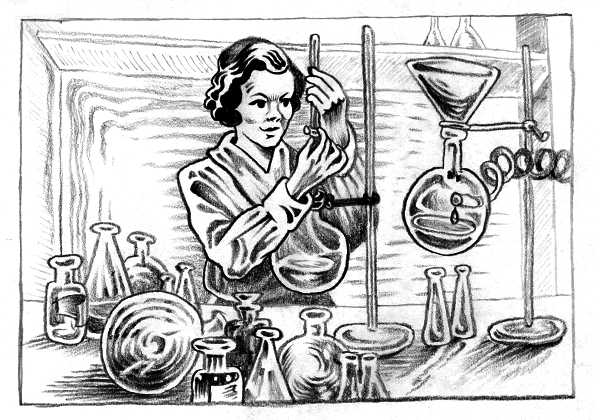

“This never would have happened if I could wear pants,” Cherry sobbed at Mr. Sandler, the chemistry teacher, as the stretcher took her away from fourth period science.

“But there’s a dress code,” he said, as though that explained away his responsibility for her wounded legs. “I didn’t do anything wrong except enforce the school rule.”

At the hospital, the nurse slowly picked out the skirt fabric with tweezers from the chemical burns on Cherry’s legs, shaking her head at the damage. The nurse knew that this could have been avoided if Cherry had been wearing the proper kind of clothes for the task in class.

Eventually, a male doctor came in with a clipboard.

“You should be more careful,” the male doctor said to Cherry. He looked like a movie star. “Chemistry isn’t for everyone. Try switching to a more ladylike class.”

Cherry glanced at the nurse, and as she applied a gauze pad on Cherry’s wounded legs, the nurse’s eyes seemed to say, You know, honey, I got top marks in my chemistry class. Higher than he did, he was middle of the pack. So maybe don’t listen to him and keep taking those science classes.

The nurse finished up and nodded at Cherry as her mother rushed into the room.

“What did you do?” her mother asked as she fussed over Cherry on the bed.

Her mother looked immaculate as always. Hair coiffed. Face perfect. Smart dress. Shiny handbag. Gloves on. She could have been an actress with her looks.

“Nothing,” Cherry said. “There was a small earthquake and the vial got knocked over. Billy got some on him as well, but all he got was a hole in his pants.”

“I don’t know why you have to be so different,” her mother said as they pulled out of the parking lot and onto Sunset Boulevard. “I feel as though I’m always having to explain you to all my friends. Their daughters never cause this kind of trouble. Or take chemistry.”

Cherry knew her mother expected her to say she was sorry about her interest in science, so she said it, but she didn’t feel it. After all, the Russians just launched a dog into space but girls couldn’t wear pants. Still, she knew what she had to say.

“I’m sorry.”

“This incident of yours is interrupting my schedule, so I’ve arranged for you to stay with Mr. Hartmann while you heal.”

This news hurt Cherry more than the wounds on her legs.

“Excuse the mess,” Mr. Hartmann said as he opened the door to let Cherry in. “I’m trying to categorize my things from the attic. Perhaps you can help me while we spend this next little bit of time together, Cherry.”

“I’m injured,” Cherry said.

“Of course,” he said, then indicated for Cherry to sit in a large leather armchair in the jumbled office and handed her a yellow legal pad of paper. “Perhaps you could jot down my notes as I unbox things?”

Cherry sighed. Mr. Hartmann’s house was a cozy, cluttered mess. It was full of film memorabilia: shelves of awards, piles of scripts, film theory books, parts from old cameras, and various pictures of the glamorous old Hollywood days. Mr. Hartmann started to go through boxes and told Cherry what to write down. The names of books: The Film Sense, Cahiers du Cinema, The Haunted Screen. The different kinds of clocks: mantel clock, cuckoo clock. The beautiful lamps and ornate candlesticks. Then he stopped droning on when he opened a box in the corner. Instead, he gave out a little gasp.

“What is it?” Cherry crouched back in the chair, worried that it was a spider or a rat.

Mr. Hartmann turned to her with a glint in his eye and pulled out some old dusty, dirty film reel canisters.

“I thought these were lost. Shall we see what’s on them? Perhaps they’re not too damaged,” he said. “I have a projector in the garage.”

Cherry shrugged.

“Excellent. You stay there and make yourself comfortable.”

Cherry watched as he busied himself getting everything ready. He wheeled in two different-sized projectors and a large screen and set them up.

“I think you’ll like this one, yes? This one was co-directed by a woman,” Mr. Hartmann said. “I knew one of the directors. The man. His name was Zoltan. We crossed paths here in Hollywood. His wife starred in this one.”

He dimmed the lights and then moved behind the projector, threading the film into the reel.

The film was maybe thirty years old, called Men of Tomorrow. Cherry sat up in her chair and leaned forward. It was about a female chemist.

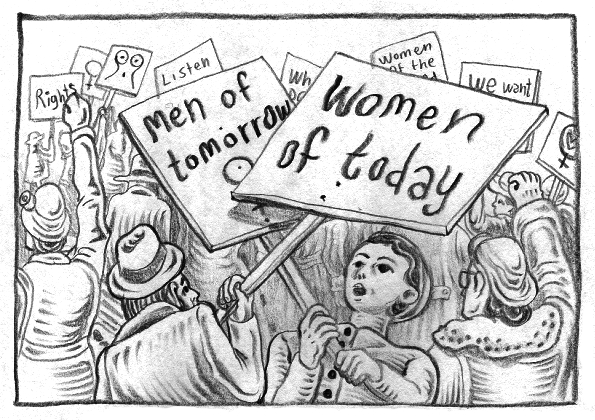

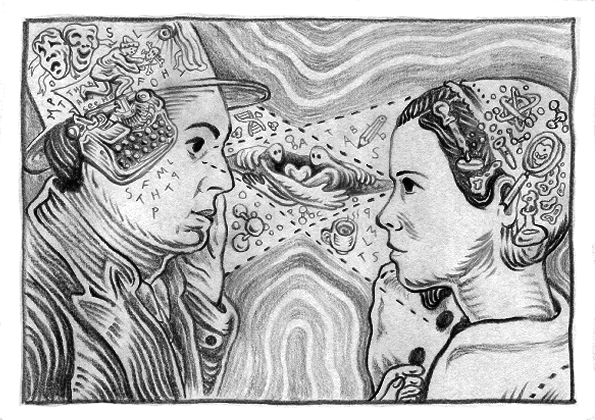

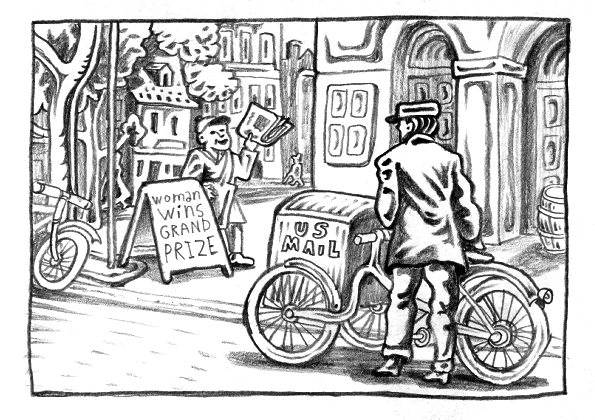

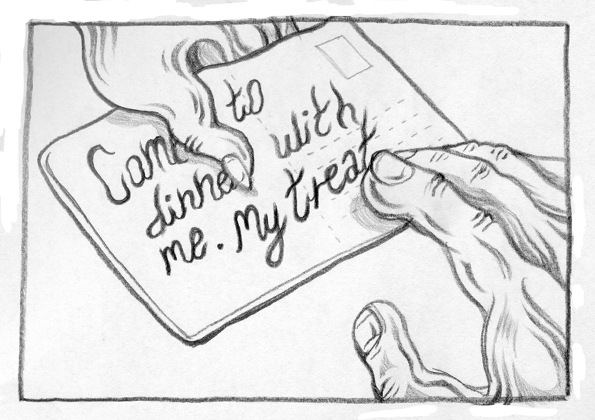

Allan and Jane meet at an Oxford march for equality for women. Allan falls hard for Jane, who is studying science. They get married and she quits her studies in order to support Allan, a novelist, with his career. When he gets in trouble for writing a novel that criticizes Oxford, he loses his teaching job and his novel contract. Desperate for money, Jane takes a job with her old professor at Oxford to work in his lab. She starts to thrive and Allan feels emasculated. Their idyllic relationship starts to crumble as takes on domestic duties and his hidden biases against women rear their ugly head. They separate. Allan’s life spirals downwards and he becomes a mailman. Unshackled from his unconscious misogyny, Jane gets her PhD and wins a big science prize. Allan sees her in the newspaper and feels so proud of her. He reaches out to her so that they can have dinner. Jane sees that he is truly a changed man. He has learned and grown in their time apart, just as she has. He is ready to meet her as an equal. He is now a man of tomorrow.

“When did this movie come out?” Cherry asked.

“1932,” Mr. Hartmann said.

Cherry tried to imagine the boys in her classes, like Billy, one day treating her with the same respect that they treat the other boys. It was hard, but watching this film ignited a kind of hopeful chemical reaction inside of her. If someone could imagine a story like this in 1932, then perhaps there was a place for her in a lab one day.

After the final reel played out, Cherry knew one thing for sure.

On Monday when she went back to school, she would wear pants.

Age Twenty-Six

On the first day of college, Cherry woke up, put on her favorite pleated pants, tied her hair up in a low bun, wore no makeup, walked to campus, donned her lab coat, and headed into the lab.

No one stopped her like they did in high school. No one sent her back home to change. No one noticed her amongst that crowd. There was a freedom in that invisibility: no boys batted an eye, no teacher did a double take, no girl sized her up with suspicion.

Cherry slid in behind her station and began running her experiments. It wasn’t until the bell rang and she got up that the professor even noticed her.

“Oh, Ms. Vanlin. You are here. I had marked you as absent.”

“I’ve been here the whole class.”

As she pointed to her station, she could see that he was looking at her pants.

“There’s a dress code in the lab.”

Pretty much every one of the other male students around her snickered. Cherry ignored them. She was used to doing that. But she nodded at the one who didn’t. She knew she was safe to be herself with him. It was a reminder to look for those kinds of guys in the room.

“Yes, Professor,” she said, pointing to her lab coat. “Lucky I found a small one on mail order over the summer. It fits me properly, don’t you think?”

The professor pointed to her slacks.

“I think we both know that it’s safer in the lab for me to wear pants,” Cherry said.

“You’re breaking the university rule.”

“In a way, we could say my doctor prescribed me these pants. I’ve previously had a chemical burn. Would you like me to show you the scars?”

Cherry put her hands on her pants buttons, ready to show off her bare legs if need be.

The professor put his hand up in front of him to stop her.

“Get the prescription for pants on file with the secretary so that I don’t get reprimanded about not following the rules.”

It took three doctors laughing at her, before the fourth, a woman, gave her one.

When she handed over the prescription to the department administration, the secretary rolled her eyes in sympathy, filed the paper away, and went back to reading The Feminine Mystique.

Age Thirty-Six

Cherry had a big decision to make that summer. The department head decided to cut her funding and funneled the grant money he’d received in favor of a younger man who styled himself as a maverick with new ideas. Cherry’s work was edgier than his, had more promise, and she had more experience in the field, but it didn’t matter. She thought about leaving abruptly in a huff. But not returning would set her back in the pursuit of her PhD.

And Cherry wanted a PhD.

She felt humiliated back in her childhood bedroom, surrounded by boxes and suitcases. She missed the apartment she’d had in the all-women’s independent living hotel. She felt sorry for herself and her mother didn’t make her feel any better about it.

“Well, who ever heard of a scientist named Cherry anyway?” her mother said while serving Cherry a slice of meatloaf.

She wanted to say something, but instead, she put a forkful of food in her mouth as her mother buzzed around the kitchen.

“I’m sure you did something to make him let you go,” her mother said. “I told you you’re too much of a feminist.”

“That’s not a bad word,” Cherry said, but her mother went on. “And he didn’t let me go. He cut my funding. I’m thinking of leaving the lab.”

“In my day, we never did anything unruly like that. Why don’t you use your ladylike charms to get what you want?”

“What?”

“How can you be so smart and so thick at the same time, Cherry? Just tell him you’re sorry, tell him you’ve fixed your wayward ways, bat your eyelashes, and then it all will be set right.”

There was such a difference between them that Cherry knew it could never be bridged.

“I don’t need to change,” Cherry said. “He needs to change. Society needs to change.”

She thought about Allan and how he’d grown to understand Jane.

Cherry’s mother laughed. “I can’t even have a bank account without a signature from your father.”

“That’s about to change with the Equal Credit Act,” Cherry said.

“We’ll see,” her mother said.

Cherry wished she could go out for a classy cocktail and talk to someone about it, but all her friends from high school were at home with their husbands and new babies. Besides, they wouldn’t understand. They still thought she was strange.

“I’m going outside to smoke a cigarette,” Cherry said.

She grabbed one from her purse on her way to the backyard patio to give herself space from her mother. She lit a cigarette and looked up, noticing the light was on in Mr. Hartmann’s house. Mr. Hartmann’s house had always been a refuge ever since he’d shown her those movies when her legs were healing. She continued to escape to his house throughout the rest of high school and watched movies long after her convalescence. She almost went back into the kitchen to ask her mother if she could go over and visit Mr. Hartmann, but then she stopped herself. She was a grown woman and didn’t need permission.

Cherry walked over to the break in the bushes and stepped through. and it was almost as if she herself was going through a portal to a magical place. The two lemon trees were in full bloom and smelled delicious. The cracked dentil moulding looked charming. The faded maroon and blue trim felt nostalgic. The bougainvillea crept up the house in a way that promised secrets within.

“I thought I saw you arrive yesterday,” Mr. Hartmann said, standing framed in the door, looking like a wizard. His smile was so big and warm that she thought maybe he’d crack in two. “I was hoping that you’d remember me enough to say hello.”

He’d gotten older, like he’d aged one hundred years since she’d last seen him. She couldn’t even remember when that was, since she’d been so busy away at school, making herself a life.

“I know why you’re here and I already pulled the boxes that hold your very favorites,” he said as he ushered her inside.

Cherry felt a warmth in her body as she followed him into his small kitchen. She watched as he put on a pot of water for tea.

“I’ve been keeping up on your triumphs. I am so proud of you,” he said. “Now, tell me everything.”

She told him it was hard being one of only three women in the department. That most of the men ignored them. That her thesis advisor implied that women shouldn’t pursue a doctorate because they always dropped out of the field when they got married. That she hated that she had to work for men rather than pursue her own research because she had trouble getting her own grants. That she felt demoralized. As she unloaded her burdens on him, she felt seen. Like her life was his favorite movie.

Mr. Hartmann sat across from her and made comforting noises. He offered no advice, only a friendly ear. Then he patted her hand and fired up Men of Tomorrow on the projector.

The flickering of her favorite of all the films he’d ever shown her had a steady grip on her. Cherry released herself to the narrative, marveling about how she always found something new in the story. How when Allan cooked, you could see him excelling at a new skill. How Jane’s hair changed as her confidence grew. How as Allan observed people on his mail route, you knew he was still working on his craft. How Jane zipped her own dress to go to the award ceremony. She felt the particular calm and sweetness that comes from watching a movie that one knows by heart. That was the magic that a favorite film had; it sparked a chemistry between viewer and story.

Their march toward tomorrow made Cherry believe that somehow, even outside of the silver screen, without her own acts to follow, things could turn out alright for her.

That summer Cherry spent many evenings sharing tea and watching movies with Mr. Hartmann exactly the way she had as a teenager. They went through all of the reels in the boxes once and then watched her favorite ones again. There was nourishment to be had in those films that she’d loved so much as a youth. They helped her breathe and think and concoct a plan for herself moving forward. By the time the fall swung around, Cherry knew what she was going to do. She was going to apply to teach at a smaller, less prestigious college and pursue her research—on a lower level, but on her own terms. She’d build up a department instead of trying to join and be a cameo in a prestigious one. She wouldn’t drop out of a life of science because it was hard. She wouldn’t let the system beat her like that. She would be the hero of her own story.

She started applying to all opportunities only using her first initial and not her full name. She landed a position within a month.

When she introduced herself on the first day, the dean did a double take.

“I thought you were a man,” he said.

“I am not,” Cherry said. “Is that going to be a problem?”

He hesitated, but then surprisingly checked himself and handed her the keys to the lab.

“Don’t make me regret it,” he said. “I don’t want to have wasted my time by hiring you.”

“You won’t have wasted your time,” Cherry said. “I promise.”

Age Forty-Six

Mr. Hartmann was dead.

“They’re selling his house,” her mother had written in a letter because her mother still refused to try the internet. “I think he left you some boxes. I put them in the backyard. It looks like it’s a bunch of metal junk. If you don’t come soon, I’m going to throw them out.”

Cherry rushed home to go to the funeral. When she arrived, there were people clearing Mr. Hartman’s house. The boxes with books, awards, and out of date furniture were on the street in an overflowing dumpster. Cherry felt gutted when she realized he had no family except his statues, memorabilia, and memories.

“Isn’t it an eyesore?” her mother asked. “The boxes he left you are out back.”

Cherry retrieved the familiar boxes of reels that housed the films she’d loved for so long. When she opened them up, she realized they’d been left out in the rain. The chemicals had crystalized. The film strips had fused. It was hard to tell if there was anything salvageable in there. Cherry cried. And then she went to go rage at her mother.

“Why did you leave them outside?” she shouted.

“It’s a bunch of junk!” her mother said. “Who would want old stuff like film when we have videotapes now?”

“You could have brought them inside,” Cherry said.

“I didn’t want them cluttering up the house.”

Cherry couldn’t be in the house with her mother, so she slammed the door and left the house. As she walked and fumed, she passed a young woman in her twenties wearing thick black black eyeliner and scrawled bloodred lipstick and sporting a colorful mohawk. She was on the corner handing out flyers. The flyer said, Free the Boob.

Cherry laughed.

She thought about how hard she’d fought to wear pants when she was this young woman’s age. She took the flyer and headed to the park where the protest was happening.

There were a bunch of young women, all different ages and sizes assembled, listening to a woman with a bullhorn. When the woman blew her whistle, all the women in the park removed their tops and swung their shirts and bras above their heads. There were breasts of all sizes everywhere.

Cherry smiled at the beauty of it.

An all-girl punk band started playing topless. Everyone threw their fists in the air.

Cherry reached for her own shoulder-padded blouse buttons and started to unburden herself of her shirt and bra. She let herself shake and rumble to the music until sirens cut through the sound of solidarity. Police poured into the park and descended upon the topless women and the happening scene. Everyone started to run, breasts jiggling, including Cherry.

As Cherry ran, she wondered briefly what would happen to her career should she be caught topless by the police. She clutched her clothes to her chest, not quite knowing where to go except out of the park to hide somewhere the police wouldn’t arrest her. When she rounded the corner, she saw it.

The movie theater.

It was a second run movie house, and the marquee said that it was playing a selection of silent films. She turned and waved at the fleeing half-dressed women around her and shepherded them into the movie theater.

“Here, here, we’ll be safe here,” she said to them.

Cherry went to the ticket booth, where a stunned young man sat, his eyes following the half-clothed crowd. She pulled out her wallet and paid him all she had in her wallet, hoping that would cover their entrance and his silence.

“Don’t tell the police we’re here,” she said. The young man shook his head in agreement. She figured this would become his go-to anecdote at dinner parties when he was older.

Cherry pulled her shirt back on and entered the theater and found a seat. The lights were down, the film flickered, a live piano player began to play along. Cherry’s heart was beating wildly in her chest, but it settled when, as the film went on, no lawmen entered. They’d found sanctuary here, as she knew they would. The people whom she’d brought in laughed and gasped in delight at the film, Mabel at the Wheel, a slapstick comedy that still charmed. Cherry loved as the ragtag crowd hissed at the villain, Charlie Chaplin in only his third screen appearance. Cherry wondered if the women here would be surprised to learn the director, Mabel Norman, was the one who took Charlie Chaplin under her wing and mentored him in the craft of filmmaking. Of course, because of the way things were, he became the bigger star.

The others left after the first showing, thanking her as they passed her by in the aisle. But Cherry stayed until she had forgotten she’d lost the films that Mr. Hartmann had bequeathed her.

Age Fifty-Six

Cherry was excited at the lab; things had finally gone her way. She would be first author in the scientific paper that they were working on at the university.

Cherry thought that Trevor, her romantic partner of five years who was also on the team, would be happy for her. He’d always said that she deserved more. But when the moment came, he seemed bitter. He was difficult to work with. He undermined her authority. He sulked.

It was clear that he thought that he should be in charge. He continuously undermined her authority, gave orders without running them by her, and took initiatives that muddied the experiments.

Cherry did what any boss in that situation would do. She let Trevor go from her team, swapping him out with another lab for a young female postdoc who showed a lot of promise.

This did not go over well with Trevor.

They had a big public fight on the bus on the way home. Cherry realized this progressive stance he had their whole relationship was all talk. Cherry was heartbroken to learn this about someone that she loved so much.

Cherry kicked him out of their shared home as soon as they got home.

Once the door slammed shut and she no longer had to be strong, she threw herself on the couch and sobbed. She had a sadness and rage in her that was more than the hormones that caused her hot flashes.

Cherry knew there was only one place she could disappear to that would soothe her.

Films.

She rummaged through her Criterion collection but nothing suited. She scanned the Netflix envelopes that had arrived that day to see what was on deck. None appealed.

Then her mind turned to remembering the films that she’d loved as a girl. She set about to add those to her queue. They’d arrive in a few days and would do the trick to get her out of this existential funk.

Cherry booted up her desktop computer and went to the website and started searching for all of those films. The ones that made her fall in love with cinema. Some were there, but only a very few.

Most weren’t.

For example, there was no copy of Men of Tomorrow anywhere. Almost none of the silent films she’d remembered so fondly were there either. Cherry felt disappointed but saw there was a form where one could request titles to be added to the library. She filled them out everywhere she could think of, diligently noting the year and the directors and crafting a synopsis of the story. The websites said they’d alert her when the films became available. Months went by, then years.

Still, Cherry made a habit of scanning the weekly alternative newspapers for the art house theater runs in case those films showed up in screenings. She became a regular at those theaters and then started going to the cinema festivals and joining cinema societies.

There she found a small group of new acquaintances, companions who shared the same passion for old obscure movies that she had. Every one of them had a film that hooked them in. Some were popular and easy to see. Others weren’t. These new acquaintances of hers delighted in making treks to go to movie festivals to see new prints no one had seen for years. It was never the films she remembered from her youth, but they still intrigued her. She loved when they all told each other the plots of the films they’d lost, but adored.

Sometimes they’d dress up in vintage clothing to match the era. There were Noir Fests, Silent Fests, Directors Fests, Screwball Comedy Fests, Sci Fi Fests, Horror Fests. They were all a delight.

Cherry was entering the second act of her own story. Just like in the movies.

Age Sixty-Six

The head of the department had asked her when she planned on retiring. As far as she knew, he hadn’t asked the male scientists that question. Cherry had the sense they’d like to make room for someone younger. Even though more women had joined the lab, there was still an imbalance. Cherry wondered if they had their eye on another young mediocre maverick to take her desk and funding.

Cherry mentioned it at one of her cinema society get-togethers.

“All I want to do is keep working in the lab,” Cherry said.

Someone suggested she shift her skills to film preservation.

Cherry liked the idea of working in a film lab, but it wasn’t quite what she did. Volunteering in a lab would be for later when she was old and looking for things to do. For now, she still felt that she had years of good science work left in her.

She refused to let the haughty way that the younger men looked at her when she gave instructions ruffle her. She would instead take extra time with the young women in the lab, mentoring them as she could, calling them into her office, encouraging them to apply for various grants and awards and fellowships. She could see the toll on her young, exhausted married mother scientists. And even though now it was the twenty-first century, most of the married male students were breezing through the academic life because their wives and girlfriends took care of everything else in life.

Sometimes Cherry thought maybe her cinema friends were right. That she’d better give herself something to do when it was all finished for her in the lab. So, on the weekends, Cherry began to volunteer at the image preservation society.

She would go to estate sales on the off chance that a lost cinematic gem would be there in a box.

Often, time had ruined the films beyond recognition.

But occasionally, there’d be a pristine print of something, perhaps not exactly a lost film, but still helpful to the film restoration cause. She used her skills as a scientist to help with the chemical reconditioning of cellulose acetate to prepare copies for public screenings and archives.

She always hoped that the next film would be one of the films that she was looking to see again.

She always hoped she’d find a reel of Men of Tomorrow. She never did.

When the British Film Institute officially declared it a lost but important film, she was shattered.

Age Seventy-Six

It was unbelievable to her and them that he had been elected.

Cherry had her handmade sign ready to go and took the metro down to the assembling site. She exited the station and wove her way to the meeting spot over by the big statue.

That’s when she saw him. Trevor.

Their eyes locked.

He looked good and not as old as she’d hoped he’d look by now. He was with his younger wife and their tween kid. Trevor nodded at her, an acknowledgement he’d seen her. Cherry nodded back politely and gave a little wave. She thought that would be the end of it, but instead, he took it as an invitation, and she watched as he made his way over to her. For the first time in decades, they were face-to-face.

“I’ve been hoping that I’d run into you,” Trevor said.

“Well, here I am,” Cherry said, wondering at the chances that they’d see each other in a crowd this big. “It’s good that you’re here.”

“I wanted you to know that I’m a changed man. I was a real ass when we were together. I learned a lot from you,” Trevor said nervously.

“That’s nice to hear,” Cherry said, even though nothing he said could give her back the five years he’d cost her.

“I’m trying to do better by my son, Elias,” he said, and pointed back to where his family was standing. “He takes ballet and plays hockey.”

She opened her mouth to tell her exactly what she thought of him, but instead she said, “As he should.” There was no better time to be a man of tomorrow than today.

“I’ve been following your career,” he said. “I saw that you retired. I wanted to let you know that of the two of us, you were always the better scientist.”

“But you managed to get all the grants I went for before you left research for the private sector and became rich.”

“Once I had a kid, I wanted to be a better provider.”

“Ahhhhh,” Cherry said. He smiled sheepishly at her.

“I know, I know,” he said. “You think I’m a sellout. You were always the radical one. I’ve made my peace with it, and I think I’ve made a difference. Gender parity in my lab, no matter what they say.”

“Well, good for you,” Cherry said. Of course, there was so much work to do beyond that, but at least it was a start.

“I watched a movie the other night on TCM, and it made me think of you. About how you were always looking for that movie you saw as a girl. I wondered if you ever found it or if it was still lost?”

“Oh, that film is my white whale, still lost,” Cherry said, but she was touched that he remembered such an intimate thing about her.

A speaker signaled that the women’s march would start shortly.

“I see my friends hovering over there. I’m going to go join them,” Cherry said. “It was good to see you.”

As she weaved through the picket signs to her friends, it struck her that the first scene in Men of Tomorrow began at a march for women’s rights, where the two protagonists have their meet cute.

In a way, meeting him here felt like meeting Trevor again for the first time.

He was changed and that gave her hope as the crowd surged forward and marched.

Age Eighty-Six

In the strange time of distance and isolation and masks, Cherry took solace in the fact that she could find comfort in old films.

She was glad she had remained as independent a senior as she could, so that when quarantine was called, she was safely in her own apartment and not in a home. In her later years, she had already arranged so many things to make her life easier to allow her to be self-sufficient. Her kind younger friends at the various film clubs and societies and some old, cherished students made sure to distantly deliver to her whatever else she needed.

But the truth was she didn’t need much.

Throughout that hard time, Cherry enjoyed what she always did: cooking, gardening, and a glass of wine while watching an old film. Her film group tried to do a watch along online, but none of the older members could figure out the tech to make that happen. One of the film club members tried to get their grandkid to help them all out, but they all gave up. Cherry was fine watching a movie by herself.

The characters in movies were as good company to her as a real person.

Still, she knew that with the silence of living alone and limited social interaction as an elderly woman she had to keep her mental acuity up. So, in addition to watching movies, Cherry would stare at the blank wall where she imagined a silver screen hung, and she willed herself to remember the plot of every one of the favorite lost films her long gone cinema club friends had told her.

The Painted Angel, Mademoiselle from Armentieres, London After Midnight, Manhattan Cocktail, The Betrayal, and of course, her favorite Men of Tomorrow, the only one of the lost films she had seen herself.

Scene one, a women’s march. Scene two, Allan and Jane on campus and in love. Scene three, Allan has trouble with publishing his book due to his radical views. Scene four, Jane gets a job in the lab at the school and starts to thrive, scene five…

She tried to go frame by frame, trying to visualize the way that the shots were set and how the light looked and what the characters were wearing and the expressions they made and the words they said. Trying to remember them so fully was like a memory constantly fighting with itself.

The frames would form and then immediately be snatched away.

Age Ninety-Six

Movies at a time like this were the last thing to care about. Yet Cherry still believed they were a vital escape.

Sitting in the abandoned parking lot of the Trader Joe’s, whose large wall was a perfect substitute for a screen, Cherry fiddled with the temperamental 16 mm projector. She’d found it in a studio’s dumpster, and she was amazed it still worked. It was connected to a generator that she’d traded a pair of boots for six months ago. Everything was coming together for a perfect night.

It was a clear day, with a soft wind that gave a tiny bit of relief from the heat. The sun was about an hour away from setting and you could hardly smell the smoke. There would be no moon this night, and due to the rolling blackouts that the city had imposed after the grid failed a few years ago, there weren’t too many lights either. The dark conditions would make for perfect viewing.

As Cherry sifted through the waterproof bin she had full of film reels, she wondered if anyone would even show up. Cherry knew what a pleasure it was to lose oneself in a story, but who could tell what people found pleasure in these days. Everyone was just trying to survive the weather, the wind, the social wars. It was a lot.

Still, Cherry had flyered around the neighborhood with handwritten signs CINEMA SCREENING TONIGHT. She put them on poles, walls, and abandoned cars. It was the only sure way to get any messages across these days.

As an old woman, Cherry worried there wasn’t much she could do to contribute to the world anymore, but she could provide the chemistry that happened when a group of folks watched a film together.

While she continued to fiddle in preparation for the screening, she thought back to some of her favorite films. There were so many to choose from, but the ones that she most treasured were always the ones that she’d first encountered in her youth during that summer at Mr. Hartmann’s.

She sighed at how so much of the way that people used to entertain themselves had disappeared because of all the infrastructure failures. Cherry remembered when there were countless ways to watch a movie. From the theater to the television to the computer to the phone. It wasn’t so simple now with everything that had happened.

Cherry heard footsteps approaching and turned to watch a young family enter the parking lot and spread out a picnic dinner. They nodded to her as their young boys ran around playing a game of tag. Soon a small group of surly teenagers arrived and sat together in a gaggle giggling in hushed voices, pinching each other on the hood of an abandoned truck. Soon an elderly couple set themselves up a table and chairs and served themselves wine. More drifted into the lot before sunset.

It was a small crowd, but they were there together to watch a movie and that warmed Cherry’s heart.

That was magic, no matter what the film was. That was a good thing as now almost all of those films that people put the names of in the suggestion bucket she always left out were impossible to find these days.

As she grew older in these strange times, she understood that she was part of a dwindling group of folks who had actually seen those lost films. She wondered how many of them were now left? Was she the only one? Would anyone in this world care about films from the past if it was impossible to view them? It made her feel that this night under the stars was vital to her preservation work. Thank goodness that she held onto the films that she’d loved and lost in her mind as well. She was glad that she could still almost remember them frame by frame.

The last twenty years, even before the troubles, so many more films disappeared.

Even though she eventually had to move into an independent living home, and her younger cinephile friends insisted that she downsize, try as she might, she couldn’t bear the thought of getting rid of any physical media on the off chance that she might never be able to find that film again. She grabbed 8mm, 16mm, 25mm film reels whenever she saw them at estate sales. She was glad that she had. Most of those modern formats—VHS, DVDs and streaming—were unhelpful now in these times. No one could watch them.

But with film, all Cherry needed was the generator, the projector, and a white sheet or a blank wall and whatever reels she had collected over the years.

Cherry fiddled some more with the projector. She poked through the box, trying to decide what film to thread. She tried not to notice that the reels were getting worn thin and scratched. She’d patched them back together as best she could, but it was a Frankenstein effort without the proper tools. In her fixes, scenes jumped awkwardly to another action or another scene entirely. Sometimes there were whole swaths of the story missing. She tried not to let it bother her too much. She knew the films in her collection by heart.

Instead, Cherry would stand next to the screen and shout out what had happened in the missing moments to get the audience up to speed.

“Soon,” she thought, “there will be no more of these film reels to screen. Before long, it will be me telling the story in front of a flickering light. Like the first humans in their caves, so too the last.”

When the sun set and darkness came, she turned her projector on. The gathered crowd clapped their hands and the chemistry she’d always cherished began to work its magic.

She wondered, “Is a film still a film when it is gone? Or does it become something else?”

As the movie played, she wondered again about all the ones she’d never see again. And she wondered who would remember them when she drifted on.

* Men of Tomorrow (1932) is a film by Leontine Sagan and Zoltan Korda. It is one of the “75 Most Wanted” films listed by the British Film Institute as “Missing, believed lost”.